Andy Warhol: Vapor Trail

By Trevor Fairbrother

This essay was originally published in (SIC), a Belgian magazine about modern and contemporary art (www.sicsic.be). An abridged version appeared in the September/October 2012 issue of Art New England, and appears here in full for the first time in English.

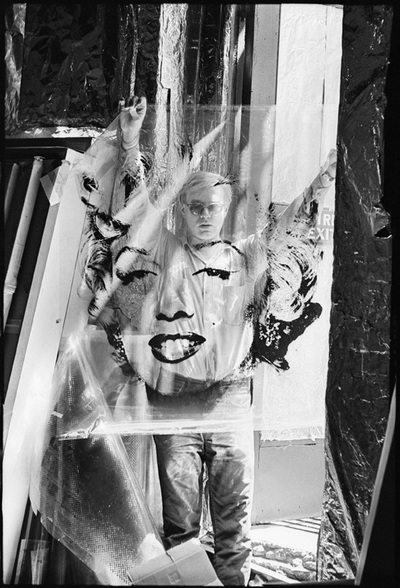

William John Kennedy, Warhol Holding Marilyn Acetate I, executed 1964, 2010, © 2011 William John Kennedy, courtesy of KIWI Arts Group.

It is about twenty-five years since Andy Warhol’s death, and history seems to be loath or unable to take full possession of him. While the post-modern 1980s have paled, he looms in the collective rearview mirror. Bits of him, from wisecracks to costly studio products, are never far away. He’s become a kind of “Exploding Plastic Inevitable,” which was the name he gave to his indecipherable raptures of sound, light, film, and music in the 1960s.

In April 1988 I gave a paper about Warhol’s Skull paintings at a symposium held at the Dia Art Foundation in New York. In these colorful and sometimes vividly brushed canvases, executed in 1976, a photo-based image of a human skull casts a shadow in an otherwise empty space. I considered the series in the context of the artist’s morbid predilections and his overarching sense of irony. My argument, based in visual thinking, incorporated: the Death in America series he talked up in the early 1960s; the role of the prominent “blank” elements he used in numerous projects; the late Camouflage paintings that were an ambiguous blend of the abstract and the specific; and the eerie work in the Myths series in which Warhol assumed the guise of an old-time radio character called The Shadow. Warhol had posed partially nude for a couple of tough realist artists (Alice Neel and Richard Avedon), allowing them to depict his badly scarred torso. And then there was the artist’s publicly expressed wish for a simple tombstone with the word “Figment;” and his hoped-for TV show that would be called Nothing Special. A Warhol Skull might be a memento mori for the proverbial Everyman, or perhaps a metaphorical self-portrait by an artist who had survived his assassin’s bullets.

Warhol wanted to be a legendary being. As a wan eight-year-old in a meager immigrant household he was writing Mick Rooney and Shirley Temple for autographed photos, and he never abandoned the dogged pursuit of Americanized celebrity. Given such an uncanny yearning for success I have begun to envision him as a lamia. This mythological creature cuts a lively figure in an early-seventeenth-century British encyclopedia called The History of Four-footed Beasts and Serpents. The illustration shows the lamia to be a leaping, lion-like animal that has two breasts, a cock and balls, and a somewhat bushy tail. The head is that of a woman with straight shoulder-length hair, and the body, with the exception of the bosom, has a covering of serpent-like scales. Its hind feet are hoofed and its front feet have cat-like claws. Edward Topsell, the clergyman and scientist who wrote The History of Four-footed Beasts and Serpents, had never seen a lamia, but he included one in his book because he deferred to the authority of certain early Christian writers. Topsell also accepted the word of the Greek historian Dio Chrysostom, who described the creature’s face as “very beautiful” and its breasts as “large and comely.” The lamia dates back to ancient times, and in some cultures it is envisioned as a devourer of crying children or a vampire-like enchanter. In a renowned Romantic poem the creature is an ill-fated seductress, who, at the beginning of the tale, is biding her time in the woods as a magnificent snake: “She seem’d, at once, some penanced lady elf, some demon’s mistress, or the demon’s self.” (John Keats, “Lamia,” 1819.)

Edward Topsell, The True Picture of the Lamia, 1607, 5.39 x 6.41″. Courtesy of Dartmouth College Library.

Warhol’s oeuvre was a volatile assortment of incongruous products, some of them brutal, resplendent, acute, or paradoxical, and others sweet, uncouth, listless, or tempting. This mongrel achievement reflected the man behind it. In the 1950s he flourished as an illustrator for advertisements, but, by the mid-1960s, he had re-invented himself as an avant-garde figure in the fine arts. Of the pop artists he was the most “pop” because he fearlessly played against those who were prejudiced against his commercial background and his gayness. He relied on visual, verbal, and social stratagems to win attention and to hasten awareness (pro or con) of his art. But the word “stratagems” is too fancy for our underprivileged Depression-Era interloper: “tricks” is more apt and more flattering. Warhol’s battery of tricks beguiled his fans and appalled his critics. The monster self that Warhol invented did not die in 1987. It thrives with a weed-like hardiness: like a fantastic mythological creature, it is too weird to forget, too perfect to tamper with, and too entertaining to renounce.

I became a Warhol fan when I was a teenager. Pictures of his work caught my eye in books and magazines at my local library in provincial England. As it happened, my background was not unlike his, for I grew up in a poor, minimally educated family in a dismal industrial place. But at that moment it didn’t occur to me to wonder about Warhol’s origins. He was just the caption underneath the images, and I doubtless assumed that anybody featured in those publications was somebody special. Prompted by an inchoate instinct for the new and for tracking things happening in places other than the one where I lived, I lodged his name and those illustrations in my adolescent brain.

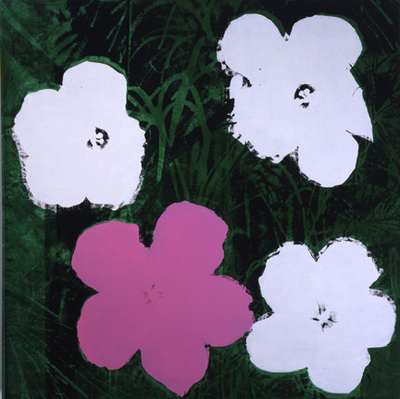

While I was an undergraduate studying biochemistry I visited the Warhol retrospective at the Tate Gallery in 1971. Although I had landed on a university path that was strictly limited to classes in the sciences, I was in a position to explore the arts on my own time. At the Museum of Modern Art Oxford, for example, I lingered over Bill Brandt’s photographs and John Heartfield’s photomontages; and at the New Cinema Club of Oxford I sought out Kenneth Anger’s Invocation of My Demon Brother and a host of films by Genet, Warhol, Pennebaker, Rocha, Warhol, and others. At the Tate’s Warhol show I remember noticing an adult couple earnestly discussing the paintings and wondering if I would be able to understand what they were talking about. Liz as Cleopatra absorbed me with its weirdly playful composition and sultry blue background. There were numerous examples from the Flowers series, but only the enormous ones stopped me in my tracks, bewildering me with their monumental bluntness. In truth, I was not a terribly informed visitor. Warhol dovetailed with my budding romance with American pop culture (from the Silver Surfer to Frank Zappa), which miraculously co-existed with a love for the historicism of Oxford, from its old walls, thoroughfares and parks to its many relations with the Pre-Raphaelite movement.

Andy Warhol, Flowers, 1964, © AWF.

The first time I hung Warhol’s art in an exhibition was in 1977. This occurred when I was enrolled in a doctoral program at Boston University. As part of an internship at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston, I helped the director select works for an exhibition drawn from local private collections. One of the things I chose was a recent Warhol print of Mick Jagger. After the show was hung, a colleague at the ICA quizzed me: “Do you really like Warhol’s Jagger prints?” It was dawning on me, the naïf, that the artist might have rigged his modus operandi. Perhaps he wanted to offend nitpicking critics, earnest professors, and snobbish curators. I had always enjoyed, in my untutored fashion, the threads of humor, surprise, and/or satire running through Warhol’s art, so I found myself ready to oppose those who wanted to pick it apart without really looking at it.

In 1980 Warhol assumed the mantle of a Historic Figure and mined his own notoriety by writing the book POPism. According to the dust jacket, he structured the narrative in terms of his “conquest of the New York art world” and his contribution to “the whole Pop phenomenon.” I now wonder if he intended to plant the seeds of his posthumous Disneyfication, if he was investing in a future when he would be enshrined as the “Master of the Soup Can.” My hunch is that POPism was mostly about jockeying the present, fitting his ’60s past to the emerging New Wave. Without saying it Warhol positioned himself as the progenitor of younger rebels like Robert Mapplethorpe and Patti Smith. 1980 was also the year when Iggy Pop (re-tooled for post-punk times) released “Ambition,” a song by the former Sex Pistol, Glenn Matlock. Iggy’s gender-bending rendition added a chilly Warholian touch to the album Soldier: “I’m the kind of girl – I want that whole wide world, nothing more nothing less … I’ve got a heart of gold, but I’m a wolf in mutton’s clothes … Don’t lose ambition.”

The first time I mentioned Warhol’s name in print was in 1984. I was now working as an assistant curator in the Department of American Paintings at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. A few years earlier I had completed a PhD on John Singer Sargent, the late-nineteenth-century portraitist. The occasion for my felicitous bit of name-dropping was an invitation to review a James McNeill Whistler exhibition that the Freer Gallery of Art for the Archives of American Art Journal. With hindsight I realize that I wanted to cast Whistler and Warhol as analogous heroes. I dragged in Warhol because I believed that his ongoing efforts constituted a significant parallel with Whistler’s historic move to create “a public aura of revolt and nonconformity within which [his] new art could exist.” Moreover, after years of work on my dissertation, it was a treat to write on Whistler, whose work I have always admired more than that of Sargent. Here is my favorite passage from the review: “Both Whistler and Warhol perceived and infiltrated the workings of prevailing art-world thinking, dividing their audience into supporters and enemies. To admire their art one had to come to terms with (accept, ignore, but recognize) all the trappings, however trivial, surrounding each artist’s persona, from his social and sexual person to the new and questionable manner in which his paintings were created. This cast the artist-rebel as a cult figure. A segment of supporters celebrated the implicit chic, while that very fashionableness ensured the opposition of stodgy, dyspeptic types who only had to hear the name to know they did not like the art. Today some people still ask if Whistler, Warhol, and their art are really strong and serious …”

I met Warhol late in 1983. A sea change at the Museum of Fine Arts had temporarily delivered the Department of Contemporary Art into the hands of my boss, and I had duly suggested that our allegedly staid institution could improve its game if it acquired a good Warhol painting. The museum owned abstract “color field” canvases by Morris Louis and his peers, but it had ignored pop art and minimalism. “I just want to get a Warhol through the doors” was the line in my head. I was given permission to explore and the quest began. The saga is too complicated to relate here, but I slowly began to feel that I was wasting Warhol’s time. Then, the year before he died, the museum purchased directly from artist his Red Disaster (1963): a grid of twelve black images of the death chamber in Sing Sing Prison silkscreened on a red ground. Warhol had decided to turn the work into a diptych by producing a “blank” (in this case a red monochrome canvas of equal size) to hang with the original picture. In the selections from Warhol’s diaries that were published posthumously there are a couple of references to this episode and I am mentioned as “The Boston Museum.”

Meanwhile, as that lengthy quest for an acquisition progressed, I asked Warhol’s Interview magazine to consider a review of my first major exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts, a survey of Boston painting around 1900, titled The Bostonians. Robert Becker, the art editor agreed, and the July 1986 issue of Interview devoted a page to the show, and illustrated the museum’s best-loved work by Sargent: the large and idiosyncratic portrait of the four Boit sisters. In his text Becker noted that I had managed to re-unite this canvas with the two huge Japanese porcelain vases that helped make Sargent’s composition so memorable. “No other painter of his time … did as much with a small dab of paint as Sargent,” he wrote, and then added, “The painting puts the actual vases to shame.”

In October 1986 I conducted an interview with Warhol in the galleries of a John Singer Sargent retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. It was published by Arts Magazine the following February, with the title “Warhol meets Sargent at Whitney.” We met in the galleries when the museum was open to the public, and Andy turned up with the young man he called his “bodyguard” (Benjamin Liu, whose stage name was “Ming Vauze”). One part of my research on Sargent had addressed the eroticism of some of male figures, especially his studies of models. When I published an essay on this topic it was met with silence from historians of American art, the verdict being that I had needlessly “outed” Sargent. What a delight it was to hear Warhol’s camp comments about the men in Sargent’s art that he found to be beautiful or sexy. In his eccentric manner he made interesting observations about a whole range of pictures, but his remarks were oblique and inverted because he maintained his routine stance as an off-hand, inarticulate, and/or silly character. For example, in front of the 1901 portrait of the sisters Ena and Betty Wertheimer, whom Sargent portrayed standing close together, the first thing Warhol said was “Who are these two lesbians?” If you take a look at that picture as if the subjects were or are lesbians it can be an insightful exercise.

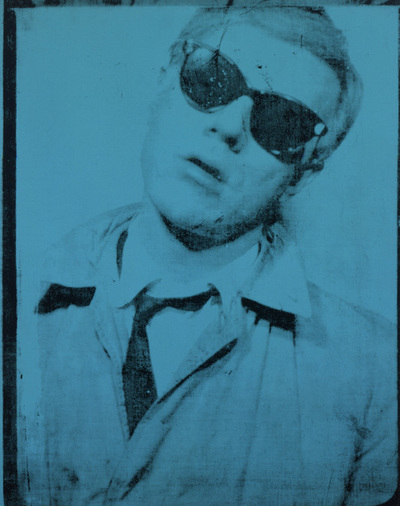

Andy Warhol, Self-Portrait, 1964, © AWF.

I found Warhol to be kind. He knew I was a fan, and he knew how to work with that. In June 1986 he took some Polaroids of me and used them as the basis for a couple of portrait drawings. I enjoyed his company, and always had the impression that he was incredibly perceptive. On the other hand, having experienced the nervous energy that characterized Warhol’s associates and his realm, I have no difficulty believing the bitter complaints of Mark Matousek, who worked grueling hours as an editor at Interview magazine in the 1980s. In a memoir published in 2000 Matousek described Warhol as “an unpleasable boss, who hovered ghostlike in the background, lobbing complaints through his bad cops, grumbling behind his frosty mask, never once saying good work or thank you.” And he remembered the job in terms of “the subjugation, the fretting over my spot on the ladder, the panting for the master’s approval.”

Even though Warhol liked to shock people by co-opting the tools and methods of commercial art, he remained, I think, sensitive about the notion that he was “only” an illustrator. When I interviewed him in the Sargent exhibition there was one moment when I think unwittingly touched that nerve:

TF: Has your background in advertising made it easier to do portraits, because in one sense they’re like products?

AW: Well, I just did shoes.When you worked in an advertising agency did you write better dialogue—better copy—after you left?

TF: But having the gifts of knowing what the client wants and how to visualize it, doesn’t that help?

AW: Actually it was the camera that made everybody look good. The camera I use for the portraits takes the wrinkles away from everybody.

In September 1988 the Dia Art Foundation hired me to make a preliminary list of works to be considered as a gift from Warhol’s estate to a proposed museum in Pittsburgh. And in 1989 I was invited to be the first director of the Andy Warhol Museum. As much as I loved the work of this artist I found myself leery about working for a three-party collaboration between Dia, the Carnegie Institute, and the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts. Early in the discussions I asked why the museum had to be in Pittsburgh, and was told that Warhol’s hometown would always love him. What did that mean? It was a contingency plan, the argument being that if the public and the art crowd ever tired of Warhol’s work the Pittsburghers would still love him as one of their own. Ever the history-minded Bostonian, I also asked why the artist’s last studio complex on East 33 couldn’t be “preserved” as some part of a Warhol museum in New York. After all, the kid from Pittsburgh had ended his career a stone’s throw from the Empire State Building, and his rehab of a former Consolidated Edison building was a wonderful reflection his melding of Art and Business. But the plan had been laid and Pittsburgh was the future.

My most gratifying project during those years was the essay I wrote for an exhibition titled “Success is a job in New York …:” The Early Art and Business of Andy Warhol. Donna M. DeSalvo organized the show, and Thomas W. Sokolowski hosted it at the Grey Art Gallery & Study Center, New York, in 1989. My essay, “Tomorrow’s Man,” explored the connections between Warhol’s art and his sexual identity. When I had my Dia-sponsored glimpse of the Warhol estate it was a revelation to find a large promotional flyer for Warhol’s services as a commercial artist. Dating from the mid-1950s, and printed in orange on thin pale green paper, it reproduced a full-length drawing of a heavily tattooed woman standing in a graceful pose with a giant rose in her hand. Her corseted athletic costume was Victorian in style, but her tattoos were strictly contemporary, for they were the corporate logos of businesses any advertiser would covet: Kellogg’s, Monsanto, Chanel, Lucky Strike, Miss Clairol, Texaco, Schweppes, and many more. Warhol’s name and garbled telephone number (“Merry Hell-3-0555” instead of Murray Hill-3-0555) filled the plain band of fabric across the showgirl’s abdomen. My foraging also turned up an envelope containing an award for newspaper advertising that Warhol received in 1952. The artist’s inscription on that envelope was “Andrew Warhol, her medal.” It was clear that he had always been ready to play the effeminate for effect, even when he was a slave of Madison Avenue in the buttoned-down homophobic 1950s. No wonder such a wealth of liberated raunchiness and cross-dressing erupted once he had nailed pop art.

The exhibition at the Grey Art Gallery in 1989 was timed to coincide with the elaborate memorial retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. The catalogue that MoMA produced was a hefty thing that cunningly ignored Warhol’s sexuality; and so too did Michael Brenson’s review in the New York Times. When Roberta Smith wrote about the Grey’s project for the same newspaper she noted a few differences between the two: “In many ways the Grey exhibition gives a fuller and more personal portrait of Warhol than its uptown counterpart. It confirms his legendary innocence and sweetness. It includes work that acknowledges his homosexuality more forthrightly.” How different the sociocultural landscape was two decades later, when Holland Cotter wrote about the 2002 Warhol retrospective at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, for the New York Times. In his review, titled “Everything About Warhol But the Sex,” Cotter declared that the artist’s queerness had been “muted if not silenced” in an otherwise major exhibition. Cotter said of Warhol: “Just by being himself, a public sissy, he automatically became one of the important political artists of his time.”

Andy Warhol, Silver Clouds, 1966, © AWF.

Warhol aspired to be everything and nothing: his activities spilled in countless directions, took many forms, and were directed at a range of audiences; and all the while he sought celebrity in the guise of a wacky, faltering nobody. There wasn’t a lot of firm ground with Warhol, and he preferred it that way. An enormous quantity of new information has accumulated since his death and there’s a lot of digging to be done. As a subject Warhol now threatens to become hopelessly large. There is so much information it is may be impossible for anyone to get him “right.”

In the 1950s a German scholar characterized Alexander the Great as “a bottle that can be filled with any wine.” Because there are few reliable early testimonies about him any portrayal of Alexander is fragmented and ambivalent. Biographers and historians are forced to invent parts of him, and in doing so they create portraits that are partly projections of themselves: sometimes he’s a homosexual; sometimes he’s a tyrant; and so on. In the case of Warhol we already have a surfeit of early testimonies, some reliable, some not, all complicated by the fact that the artist himself cultivated a stance of detachment, irony, and faux passivity.

For their comic opera The Pirates of Penzance; or, The Slave of Duty (1879) W. S. Gilbert and Arthur Sullivan wrote a song that proclaims: “How quaint the ways of Paradox! At common sense she gaily mocks!” Warhol, like the Victorian musical duo, relished people with a “taste for curious quips, for cranks and contradictions queer.” At the end of the show Gilbert and Sullivan reframed the lawlessness of their pirates and revealed that they were merely patrician misfits, “noblemen who have gone wrong.” A century after they wrote the line “a most ingenious paradox” Warhol embodied it.