Lavaughan Jenkins

I meet Lavaughan Jenkins in his modest second-floor studio near Boston’s SoWa Art + Design District. It’s one of several artist spaces in an old walk-up, tucked down a side street and embedded within a block of brick façades that has miraculously avoided development. Up the stairs and down a winding hallway, I find Jenkins in a paint-stained getup amongst his work and with much to be excited about.

A 2005 graduate of the Massachusetts College of Art and Design, Jenkins has recently received the 2019 James and Audrey Foster Prize from the Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston where his latest work is being showcased. He is also fresh from a trip to Los Angeles where he experienced a string of several firsts: his first solo show on the West Coast, eating at his first vegan sushi restaurant, and seeing the work of Philip Guston—his painting guru—for the first time in person.

“My mind was on fire,” Jenkins says of looking at Guston’s paintings up close. “Like that orange was in his painting,” Jenkins remarks, pointing to one of his own: a small, three-dimensional female figure standing upright on a platform. Her body is a deep black and her copiously painted, sleeveless dress a striking orange.

Up until 2017, Jenkins worked solely in two-dimensions. His pieces were thick and expressive figurative oil paintings inspired by Francisco de Goya’s varied representations of women as well as memories of important individuals throughout Jenkins’s life. However, it was Guston, not Goya, who ultimately led Jenkins to switch gears.

According to Jenkins, Guston appeared to him in a dream and urged him to abandon the confines of the canvas. Jenkins took the advice and since then has created hundreds of 3D figures that each riff off the same basic form. “The Philip Guston dream is probably the only reason I went three-dimensional,” Jenkins says, explaining that it was only after the vision that he began to appreciate Guston’s paintings and admire his distinctive visual language of re-occurring objects. “[Guston’s] work gave me the nod that you can find a shape and continuously repeat it.”

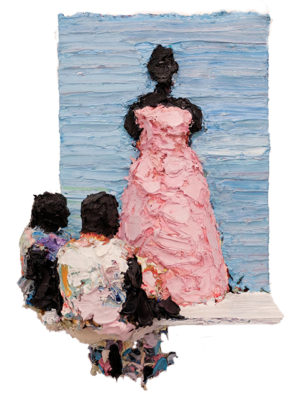

Numerous iterations of Jenkins’s figures—both male and female—populate all areas of his otherwise minimal studio. The vibrant characters stand, kneel and sit no more than 11 inches tall on panel platforms, each composed of a unique palette of bold colors. The majority of the figures’ heads and arms are painted a rich black, contrasting the pop of their attire. They are elusive and enticing, bearing no discernible features, yet each exuding a palpable presence. The male figures tend to sport fleshy physiques and multicolored blends that suggest jeans, t-shirts and sneakers, while the magisterial, goddess-like females boast dresses and ball gowns.

While sculptural in form, Jenkins assures the figures are paintings in practice. Miniature foam skeletons that Jenkins crafts and covers in modeling paste become blank surfaces for luscious daubs of oil paint. The figures’ bodies fill out as Jenkins adds layer upon layer of churning hues. “I love the process,” Jenkins says, comparing building a new figure to conventional painting preparation. “It’s just like when you’re stretching your canvas and starting to prime it, and those ideas start to play around in your mind. That process gets all your emotions going.”

When questioned for titles, Jenkins strays from a definitive answer. He hopes to leave room for new interpretations as the figures and their identities continue to evolve. Like coats of paint stacking up over time, it seems the figures amass new meaning and influence as Jenkins hones the series. While early figures were still motivated by sources like Goya from his two-dimensional days, the idea behind has branched out, Jenkins says. “Now, I’m looking at Mesopotamian sculpture for gift bearers and Egyptian art.” One part of the evolution is sure, however: Jenkins plans to go bigger. He says the next versions of the figures will graduate from “Oscar-size” to three feet tall.

______________________________________

Stace Brandt is an artist, writer, and musician based in the Boston area.