Is Art Really Just a Luxury?

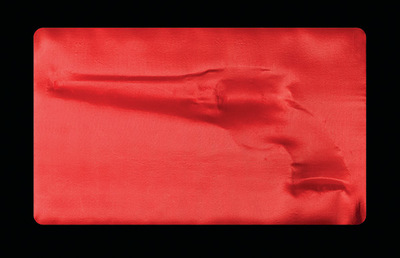

Jordan Kessler, .44, 2016, archival pigment print mounted to aluminum, 26 x 43″. Courtesy of the artist and Pitch Black Editions.

It’s easy to find voices that tell us that art is a luxury. They come from legislators who have doubted the value of an art or humanities degree. They babble at Art Basel, where the 1% turns contemporary art into the latest luxury good. They echo in our own heads on Sunday mornings when, disheartened by the world around us, we flip shamefacedly past the front section of the newspaper and take refuge in the pleasures of Arts & Leisure.

Audre Lorde, the deceased writer, critic and black lesbian feminist whose fierce mind, bold voice and unbreakable heart are much missed in this grim summer of 2016, would have none of this. What Lorde wrote in 1973 about poetry—that it “is not a luxury” but “a vital necessity of our existence … the quality of the light within which we predicate our hopes and dreams”—is just as true today about the visual arts. The insistence that art has a necessary place in political change is hardly new. It was stated at the Paris Commune in 1871, at the corner of Haight and Ashbury in 1968, on the streets of the East Village in the 1980s. But the fundamental questions recur: Where does art-making fit in the agenda of a social movement? Can artists be politically useful? Or are the voices inside our heads onto something: Is art really just a luxury?

Amy Orr, House of Cards (detail), 2012, plastic cards mosaic and assemblage on wood armature, 11½ x 7½ x 18″. Photo: John Woodin.

A recent burst of politically themed exhibits across New England show that artists are not sitting silently during our contentious political moment, nor will they concede art’s irrelevance. First of all, art is a survival mechanism that preserves humanity in times of destruction. While archaeologists and videographers map the priceless treasures that are being systematically destroyed in the Syrian Civil War, it remains for ordinary Syrians to generate new beauty. Franco Pagetti, an Italian documentary photographer with a long resumé of war-zone assignments, captured those impulses in Veiled Aleppo, a large-format photographic series on view last season at the Worcester Art Museum. Brightly colored bed sheets offer privacy for residents of half-bombed buildings; through Pagetti’s lens, they appear as assertions of color that reclaim seared-brown urban landscape.

Now don’t get all consoled just because some Syrians lightened up their unending nightmare with a little splash of color. As we watch refugees on the television news—whether from Iraq, South Sudan or Burma—it’s worth remembering that some of them are surely artists whose professional livelihoods have been disrupted. In Stories from Far and Near: Refugee Artists in New Haven, on view this summer at the New Haven Museum, local artist Susan Clinard collaborated with Integrated Refugee & Immigrant Services, a New Haven NGO, to identify seven refugee artists living and working in the area. In Protection, a sculpture by Iranian artist Dariush Rose, large wooden hands surround a vertical array of small clamoring faces. Do the hands enfold strangers with comfort? Or are they closing the gate in fear?

Elsewhere, artists interrogate and historicize the refugee experience. At the Fairfield University Art Museum, Rick Shaefer summons Baroque masters in The Refugee Trilogy, a massive triptych painstakingly composed in charcoal on vellum. At first glance, the seaborne refugees sweepingly depicted in Water Crossing look like something from the 16th century. Shaefer has surely done that on purpose, so that the next time we see rickety motorboats swollen with Libyan children, we know that we too are living through a crisis of biblical proportions.

Franco Pagetti, Untitled, from Veiled Aleppo at Worcester Art Museum. © Franco Pagetti.

Other artists are putting their skills to work in activist movements, among them AgitArte, Inc., a Cambridge-based collective that works across borders and genres to tackle a range of progressive social issues. The group’s new publication, When We Fight We Win! Twenty-First-Century Social Movements and the Activists That Are Transforming Our World, compiled by collective member Greg Jobin-Leeds, documents interventions around issues from environmental justice to the school-to-prison pipeline. AgitArte can often be found on the street, and When We Fight We Win! usefully documents performances, murals and street art such as October 2010’s We Shall Not Be Moved, a performance in collaboration with City Life/Vida Urbana to protest a meeting of the American Bankers Association. Engaging with this book’s gifted artists—so many of whom are young, queer, undocumented people of color—is an inspiring journey into future politics. Audre Lorde, who insisted, “Action in the now is also necessary, always,” would have loved it.

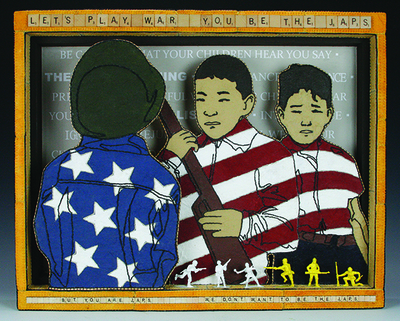

Most striking—if depressingly timely—are the many artists who have turned their gaze on America’s gun culture. They have generally chosen to engage with its materiality, as in Dave Cole’s 2013 collage American Flag (Bullets), on the cover of the previous issue of this magazine. On view this fall in Jolt: Guns, Race and Immigration at the Trustman Gallery at Simmons College, photographer Jordan Kessler’s Creased and Perforated #14 uses a close-up format and the lushness of gelatin silver printing to explore the texture of a discarded target at a shooting gallery. On view at the Brattleboro Art Center in Brattleboro, VT, Up in Arms: Taking Stock of Guns brings together nine artists who resist the urge to hide from gun culture, but also refuse to let its advocates have the last word. Susan Graham sculpts careful replicas of her father’s firearm collection in delicate porcelain; the resulting artifacts, mirror images of the heft of an actual weapon, testify obliquely to a gun’s destructive power. For some artists, the puzzle is not the gun but its owner, as seen here in a selection of images from Kyle Cassidy, whose 2007 book Armed America: Portraits of Gun Owners in Their Homes used documentary photography to generate a thoughtful dialogue with our country’s gun culture. Others seek to turn that culture on its head: In Brattleboro, Jerilea Zempel (a veteran of the Guerrilla Girls feminist art movement of the 1980s), puts a condom on a handgun. In The Faces of Politics: In/Tolerance at Brockton’s Fuller Craft Museum (April 16–August 21, 2016), Lindsay Ketterer Gates’s Stigmata stacks small plastic toy guns into a looming tower that deliberately undermines any assertion of seriousness.

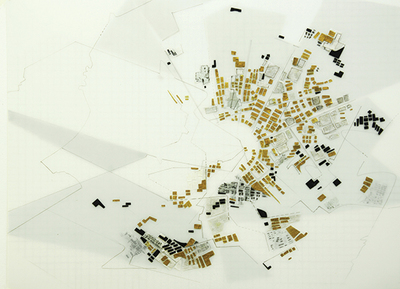

Yu-Wen Wu, Arrival, 2015, mixed media, 11 x 14″. Courtesy of the artist and Miller Yezerski Gallery.

For all the cheekiness and the bricolage, Audre Lorde would have been a little bit nervous about Up in Arms. In a 1984 essay, she reminded us “the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.” Artists’ current preoccupation with remaking destruction’s material culture “may allow us temporarily to beat him at his own game,” but ultimately, she warned, “only the most narrow parameters of change are possible and allowable.” Play with fire, in other words, and you might get burned. Or the porcelain may shatter while real guns keep firing.

Jan Hopkins, Out of the Mouth of Babes, 2015, cantaloupe peel, grapefruit peel, cedar bark, waxed linen, acrylic paint on hemp paper and mounted on wood panels, 19 x 24 x 3½”. From Faces of Politics: In/Tolerance at Fuller Craft Museum.

When New Haven industrialist Oliver Winchester began marketing his repeating rifle in the 1850s, he did not imagine the world we live in now, in which the riflery repeats with dehumanizing regularity. Several artists and activists are reclaiming that repetition to undo its numbing effect. In the series a count, local artist Linda Bond (who is also showing work in Brattleboro) marks gauze bandages with gunpowder—a medium she feels “speaks to the volatile conditions” of our times—to toll the casualties of America’s Middle Eastern wars one at a time. It’s why 30 years ago, the Names Project’s AIDS Memorial Quilt announced the individuals behind the statistics, and why Black Lives Matter activists insist today that we #saytheirnames. Restoring names gives them a history and gives us a future, which we can only make with what Audre Lorde so capaciously called “poetry.” “[I]t is our dreams that point the way to freedom,” she explained, and these artists give us the dreams we need at a time when we have never needed them so badly.

Christopher Capozzola is an associate professor of history at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.