Unmoored: Provisional Aesthetics, Rehearsing History at the Davis Museum

Where is Asia in contemporary American art? The answer according to Provisional Aesthetics, Rehearsing History, a new exhibition at the Davis Museum at Wellesley College curated by photographer and art professor David Kelley, cannot be found on any map. Along on the journey are three contemporary artists—photographer An-My Lê, conceptual artist Danh Võ, and video artist Phil Collins—who depict the intermingling of the West and Asia. But rather than acting as tour guides, these three artists are committed in their aesthetics to a provisional unsettling, leaving us unmoored from simplistic geographies of the US and Asia.

An-My Lê, Aircraft Carrier Arresting Gear Mechanic, USS Ronald Reagan,

North Arabian Gulf, 2009, archival pigment print, 26.5 x 38″. Edition of five.

Perhaps no visual artist has created a more lyrical or intellectually provocative engagement with the Vietnam War than photographer An-My Lê. Born in 1960 in a divided Vietnam, Lê fled to the United States in 1975 at the war’s end. Lê came late to photography, but she quickly mastered the form, especially the large-format five-by-seven photographs she takes with her massive tripod-mounted camera. Lê’s photographs are painfully slow to make, and the patient engagement between artist and sitter transforms her images from journalistic snapshots to meditative compositions.

Since 1994, Lê has explored the surprising legacies of the Vietnam War by “making photographs that use the real to ground the imaginary.” Reality and imagination interact in her work, most notably in Small Wars, a photographic series that depicts Vietnam War re-enactors in suburban Virginia, and in 29 Palms, where Lê photographs US Marines training for deployment by acting out the Iraq War in the deserts of Southern California.

At the Davis Museum, Lê—who won a 2012 MacArthur Foundation “genius” grant—presents eight photographs from her new series Events Ashore. For the last several years, she has journeyed as a passenger on US Navy vessels. As always, Lê is attentive to her physical surroundings, has a keen eye for the telling details of American military culture, and an eagerness to manipulate scale for unsettling effect. But these photographs are unlike anything Lê has done before. In Events Ashore, she trawls from black-and-white to color, and from landscape to portraiture. At first glance, she appears to document her Navy subjects—whether a male officer or a young female recruit—in moments of vulnerability. But then we think of that tripod camera and its extended shutter time and realize that we are witnessing a performance rather than an exposé. In military jargon, combat is “staged” in a “theater” of war. So, too, in An-My Lê’s photographs.

Events Ashore shows the US military at work in the world—Iraq, Thailand, Vietnam, Senegal, and Ghana—but not through the genre of landscape. Rather, as the US military today speaks of “human terrain,” Lê follows with her camera. Events Ashore is more explicit, some might say heavier-handed, than Lê’s earlier series. But it also reveals the paradox of the US military today, prepared for destruction but increasingly engaged in humanitarian intervention and projections of “soft power.” Lê shows us a destroyer, then boards the aptly named hospital ship Mercy. She reminds us of the soldier’s oath of duty to country and the Hippocratic oath to “first do no harm.” We feel thus unmoored—floating—on the decks of the Mercy off the coast of Vietnam, wondering whether we are harming or healing and what these young men and women are doing here.

Danh Võ, from Photographs of Dr. Joseph M. Carrier 1962-1973, 2010,

gravure on paper, set of 24 black-and-white heliogravures.

Danh Võ, a Vietnamese-born interdisciplinary artist, likewise guides us into unfamiliar territory. Ar-ranged on a gallery wall are twenty-four photogravure prints. The small black-and-white images yield more questions than answers. A fleeting glance of a marketplace, a glimpse of a swimming hole, a far-distant plume of smoke—these ethereal images are an archive that tells no clear story. The photographs feel at moments passingly erotic, then momentarily tinged with doom, and sometimes just plain odd.

Only later do we learn that the images in Photographs of Dr. Joseph M. Carrier, 1962–1973 (2010) were not taken by Võ, but by Joseph Carrier, an American counterinsurgency expert who lived and worked in Vietnam during the war and shared his collection with Võ after the two met in California in the early 2000s. Võ was born in Vietnam in 1975 during the last days of the war, and fled with his parents as a refugee in 1979, arriving in Denmark. He now lives and works in Berlin, and he recently won the Hugo Boss Prize. In his art practice, Võ habitually mines other people’s images and artifacts to tell new and unsettling stories.

Carrier’s photographs hint at intimacy and death. Although the pictures were made in Southeast Asia, the war appears here only as a backdrop. Male bonding in particular comes before Carrier’s lens and Võ’s eye: flickering images of men at an art gallery, in the marketplace, or at a riverbank suggest untold stories that might include friendship, fraternity, or even intimacy. Carrier was investigated in 1968 for having a relationship with a South Viet-namese air force officer, but Võ—who has said that he is devoted to the art of “loose ends”—leaves every story dangling, unfinished.

Võ insists that his installation be viewed as a collaboration between himself and the original photographer. But Carrier and Võ might just as well include their viewers. The work places us simultaneously in Vietnam (How can the blur of a photograph so subtly convey the sounds and crowds of a marketplace?) and in our imaginings of it. With the images unmoored from their maker, their narratives detached from the intentions of the photographer, the series implicates the viewer in the making of a narrative about Vietnam, and thereby in the long-ago violent events of Vietnam that gesture across the walls of the gallery. Only by being unmoored from history, Võ suggests, can we be forced to grasp it.

Phil Collins, dunia tak akan mendengar, 2007, part three of the world won’t listen,

2004-07, video installation, color, sound, 56 minutes. Courtesy of Shady Lane Productions

Sight and sound combine in the exhibition’s third room. In dunia tak akan mendengar (2007), British video artist Phil Collins travels to an Indonesian karaoke bar. Born in England in 1968, Collins—who now works in Berlin and teaches in Cologne—moves with comfort in the realms of mass culture. His works explore the possibilities of popular music, notably in They Shoot Horses (2004), a mesmerizing film of nine Palestinian youth at a dance marathon. The projection on view at the Davis is the third in a trilogy called the world won’t listen, which began in Bogotá (2004) and Istanbul (2005) and reaches its conclusion in these films, recorded in the cities of Jakarta and Bandung.

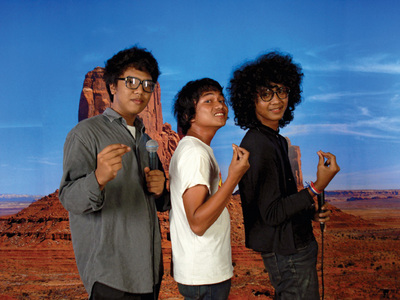

Through video close-ups, Collins finds the power of performance in the most ordinary spaces. Badly sung covers of songs by the British band The Smiths spill out into the galleries at Wellesley. (In the exhibition’s only misstep, the volume was so loud that Morrissey’s lyrics overwhelmed adjoining rooms.) Entering the projection space, we see not The Smiths, but an eclectic group of Indonesian teens captured by Collins’s camera at very close range, singing along to the band’s landmark 1987 album, The World Won’t Listen.

Watching a young Indonesian singer dressed in a baseball cap and a James Dean t-shirt performing in front of a projected backdrop showing cactus plants and a desert landscape, we might believe dunia tak akan mendengar is a story of globalization’s conquest of the world’s musical cultures. Yet Collins seizes onto the karaoke bar; he has spoken of “the power of popular culture to move people in ways that have been previously unimaginable.” We witness the singers’ vulnerabilities—perhaps genuine, perhaps only acted-out tributes to The Smiths. Collins represents a global adoption of the band’s anthems of alienation, the singers’ shared embrace of its signature lyric, “sixteen, clumsy, and shy….”

Yet there remains the matter of the cactus and the desert. Where, precisely, do these three talented artists leave us? Jakarta? Saigon? Arizona? We are intensely unmoored from place, unmoored from history, and while Provisional Aesthetics, Rehearsing History gives viewers no map to the territories, it encourages us to light out for them. That sense of dislocation traces deep roots. New England writer Sarah Orne Jewett long ago pointed out the intermingling of America and Asia. In The Country of the Pointed Firs (1899), Jewett observed that in any remote corner of her native Maine could be seen “plain, contented old faces at the windows, whose eyes have looked at far-away ports and known the splendors of the Eastern world.” New England’s global travelers, she reminded readers, “knew something of the wide world, and never mistook their native parishes for the whole instead of a part thereof.” Google reports some half-dozen karaoke bars within a short drive of Jewett’s homestead in South Berwick. There, in 2013, one might mingle with Vietnam veterans, with refugees and immigrants, with men and women who had done tours of duty on the Mercy: unsettled, unmoored, unmistakably part of the whole instead of a part thereof.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________

Christopher Capozzola is an associate professor of history at MIT.