100 Years (version #4 Boston, 2012)

Boston University Art Gallery • Boston, MA • www.bu.edu/art • January 19–March 25, 2012

Just over one hundred years ago, the Italian poet and Futurist movement founder Filippo Marinetti published his Futurist Manifesto in French and Italian newspapers. While calling for the glorification of war, contempt for women, and the burning of libraries, he also challenged artists to dedicate their bodies to acts of artistic creation.

The organizers of the exhibition 100 Years (version #4 Boston, 2012) at the Boston University Art Gallery posit that Marinetti’s text represents a seminal point in the history of performance art, when the body and movement became accepted media for representation. They draw a line from Marinetti to contemporary artists like Kalup Linzy and Ryan Trecartin, whose performative works scramble the politics of identity in a world where American Idol and YouTube set the parameters for selfhood.

The exhibition is an introduction to the history of performance art, which “has been entirely missing from the history of art so far,” according to RoseLee Goldberg, director of the performance art biennial Performa, and co-curator of 100 Years with PS1 director Klaus Biesenbach. The show includes a facsimile of Marinetti’s 1909 text, paired with approximately 210 other works from a fairly strict chronological representation, leading up to 2009, when Linzy wrote, directed, voiced, and starred in his video Melody Set Me Free, featuring Whitney Houston-crooning reality show contestants.

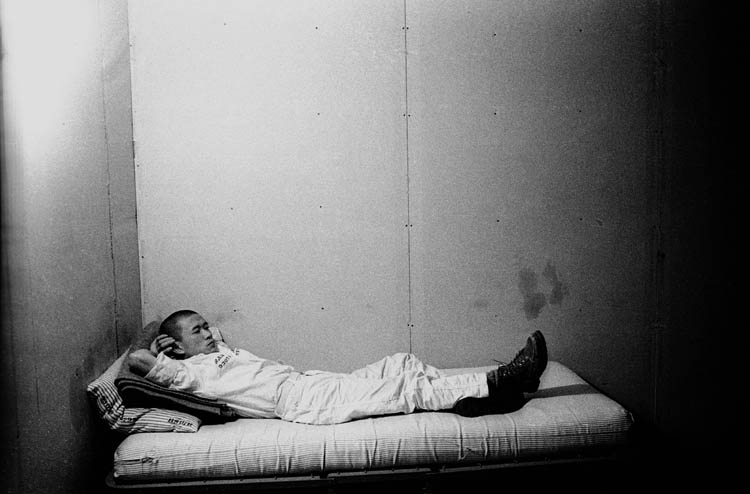

The bodily dedication to art Marinetti called for is most evident in works like Tehching Hsieh’s One Year Performance (1980–1981), in which the artist punched a time clock every hour on the hour for an entire year, taking a photograph of each instance—a process which resulted in a short time-lapse film. Hsieh created a series of such works, one of which involved him being locked in a jail cell-like cage for a year.

The exhibition also notes the transformation of art into concept, as ideas alone became media for artistic representation. Yoko Ono’s Painting to Hammer a Nail In (1961) pushed the limits of painting into the conceptual realm by exhibiting a white board and inviting viewers to hammer nails into it.

One of the reasons why the art-world establishment has resisted performance art is its ephemeral nature. It is, at times, impossible to recreate and difficult to document. The curators became archivists as they traced backwards through the Bauhaus and Dada movements. Though photographs of a star-headed Marcel Duchamp can be seen from his work, Tonsure (1919), the show is very text heavy—a forgivable offense given the limitations technology one hundred years ago.

There are some resourceful examples of documentation from recent times, such as a reprinted review by art critic Jerry Saltz from the Village Voice, in which he described the artist Trisha Donnelly riding into a New York gallery on horseback as if she were a messenger from the Napoleonic wars (“Thinking Outside the Box” Oct. 2004). The piece is appropriate because Saltz also touched upon another difficult aspect of performance art: its frequent inaccessibility. He wrote that Donnelly was “full of fetching ideas” but the art was “fairly forgettable,” “difficult, sparse, and hard to parse,” symptoms of what Saltz called “Vito Acconci syndrome.” The BUAG includes photo documentation of the notably cerebral Acconci’s Following Piece (1969), in which the artist literally followed strangers, sometimes for hours, until they entered a private space.

100 Years is a “draft,” according to Goldberg, a curatorial approach that fits the historization, or canonization, of works that have resisted the canon have been added and subtracted from each one of its four versions, including pieces from local artists. BUAG director and chief curator Kate McNamara, who assisted Goldberg and Biesenbach on 100 Years, worked with Cambridge-based performance collective Mobius and artist and RISD professor Kurt Ralske, among others, to build a program around the exhibition.

—Christian Holland