THE WILLIAM S. PALEY COLLECTION: A TASTE FOR MODERNISM

Portland Museum of Art • Portland, ME • portlandmuseum.org • Through September 8, 2013

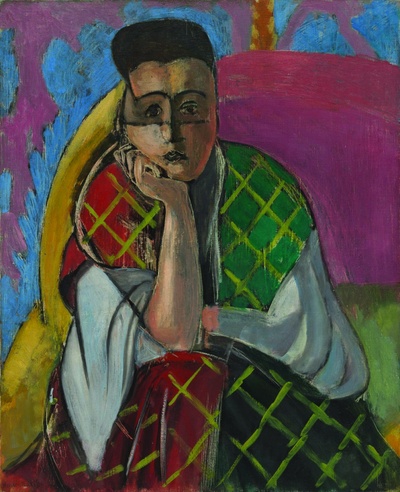

Henri Matisse, Woman with a Veil, Nice, winter-spring, 1927,

oil on canvas. 241⁄4 x 193⁄4″. The William S. Paley Collection.

In this 100th anniversary year of the 1913 Armory Show in New York City, it is remarkable to consider how exciting and troubling the arrival of modern European art was to America. Picasso, Cézanne, Duchamp, Matisse, and company disrupted the aesthetic status quo. While embraced by many of their stateside artist brethren (consider Marsden Hartley, the Zorachs, and Max Weber, among others), they were verbally tarred and feathered by the public and by many critics.

The sixty-two pieces in this exhibition, drawn from the extraordinary collection that media tycoon William S. Paley (1901–1990) gave to The Museum of Modern Art, represent a choice cross-section of the art of that time, still mesmerizing and moving despite its antiquity. It’s an all-star haul: cubist masterworks by Braque, Gris, and Picasso; classic Cézannes, including a view of L’Estaque that once belonged to Monet; several Gauguin Tahitian subjects; signature pieces by Toulouse-Lautrec, Derain, Vuillard, and Bonnard; and sculpture by Maillol and Rodin. Matisse and Georges Rouault are given mini-retrospective treatment with six oils each.

While there isn’t a single woman artist in the show (they were few and far between back in that day and age), there are plenty of female figures on view, from Bonnard’s Reclining Nude to Gauguin’s Washerwomen, and Matisse’s Odalisque with a Tambourine. In and among these modernist gems one finds a few aesthetic outliers. A couple of twisted-visage pieces by Francis Bacon; a Hopper watercolor of Charleston, South Carolina; and an industrial landscape by John Kane may inspire double takes.

The catalogue that accompanies the show, which is making its only New England stop at the Portland Museum of Art, offers picture-by-picture analysis by art historians William Rubin and Matthew Armstrong. Along with close and enlightening readings, they manage to rekindle the excitement these artworks created when they gained our shores way back when.

In his preface, Rubin notes that the objects Paley collected were generally “intimate in both format and character.” Exemplifying these traits are still lifes by Manet and Renoir; respectively, a couple of roses and a clutch of strawberries that are simply exquisite.

—Carl Little