Electric Paris

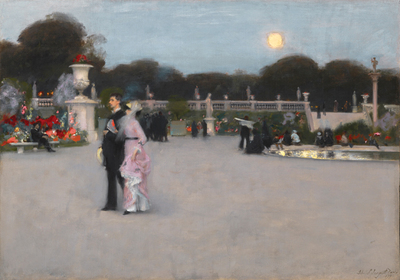

John Singer Sargent, In the Luxembourg Gardens, 1879, oil on canvas, 25 7/8 x 36 3/8″. Philadelphia Museum of Art: John G. Johnson Collection, 1917, Cat. 1080. Courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

“Because my love is near!” Frank Sinatra belts, crooning Cole Porter’s lyrics from his song, I Love Paris about why he adores the city. For those of us without French sweethearts, “Art!” is a solid second choice. Happy news for New Englanders: the Bruce Museum offers lots to love in its elegant, atmospheric exhibition Electric Paris—an expanded version of a show mounted at the Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, Massachusetts, in 2013.

At the Bruce, Electric Paris features approximately 50 paintings, prints, photographs, and drawings that exemplify the influence of artificial lighting on the Impressionists and their contemporaries. There is a mix of European and American masters: Edgar Degas and Mary Cassatt, John Singer Sargent and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, among many more. The uniting theme is illumination. Not only was Paris the center of education and philosophical thinking in the Age of Enlightenment; by the 19th century, the city was known for its widespread adoption of artificial lighting—first gas lamps, then electric ones at the approach of the new century. As nicknames go, “The City of Light” was brilliant.

Theodore Earl Butler (American, 1860-1936), Place de Rome at Night, 1905, oil on canvas, 23 1/2 x 28 3/4″. Terra Foundation for American Art, Daniel J. Terra Collection. Photo: ©Terra Foundation for American Art, Chicago.

As is the evocative artistry that it inspired. “The visual effects of light and lighting––whether sunlight, moonlight, candlelight, or spiritual light––have fascinated artists for centuries,” says exhibition curator Margarita Karasoulas, who hopes that “viewers will come away with a deeper understanding of how artists responded to changing technologies and the new, brightly lit urban environment.” For emphasis, the exhibition is divided into four thematic sections: Nocturnes, Lamplit Interiors, Street Light, and In and Out of the Spotlight, which examines the spectacle of artificial light in Parisian cafés, theaters, dance halls, and cabarets. The art ranges from nostalgic to glamorous, shadowy to starkly radiant, and showcases various inventive techniques used to make light flicker off café tabletops or gleam on the inky river Seine. Sargent’s In the Luxembourg Gardens (1879), categorized as a Nocturne, marks a transitional moment between sunset and dusk. Painting with milky lush lavenders and deep moss greens, Sargent represents competing forms of celestial and artificial light: a couple strolls under a rising moon while gas lights sparkle in the background and cause glittering reflections on the surface of a pond. Toulouse-Lautrec’s lithograph Miss Loïe Fuller (1893), an abstracted portrait of the titular American-born dancer, incorporates gold and silver powders to capture the thrill of performance on an electric-lit stage. At Belle Époque cabaret halls like the Folies Bergère, Fuller became famous for swirling in a white dress under changing colored lights. Captivated, Toulouse-Lautrec produced 60 impressions of this print in total, each awash in a combination of hues different from the one on view at the Bruce.

Also displayed are six early photographs by Charles Marville, graceful metropolitan compositions centered around gas lamps newly installed on Parisian streets. In the words of Karasoulas, “The pictorial clarity and detail of these photographs is striking…they have become iconic of Paris as the City of Light.”

Electric Paris joins together for the first time a group of works that emphasizes the role of artificial illumination in the making of modern Paris. Indeed, with the most recently dated pieces in the show—a 1913 painting, Electric Prisms, and a 1915 study in gouache, both by Ukrainian-born Sonia Delaunay—we observe the move toward Orphism by an artist experimenting with colors as well as shapes to emulate motion and depth. It’s an optical feast of vibrant wheels and halos, an exciting counterpoint to the more representational paintings in this show. Where Sargent romances with twilight, Delaunay shines rainbows into your eyes.

The exhibition is enhanced by related programming throughout the spring and summer, including chamber music, scholarly lectures, and a French film series held at the museum. And given the Bruce’s dual mission to promote both art and science, visitors can satiate their technical curiosities down the hall at the complimentary exhibition Electricity, brought to Connecticut by way of The Franklin Institute in Philadelphia. Electricity runs from May 14 to November 6, 2016 and promises interactive experiences in magnetic fields, electric charges, and battery technology for visitors of all ages. As the Bruce Museum promises, “Sparks will fly—safely.”