Toulouse-Lautrec at Three New England Museums

In late-19th-century Paris, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec was renowned for his decadent lifestyle and his vibrant artwork. Today, he is still in the public consciousness, and the subject of books, movies and countless exhibitions including three this fall in New England—at the Bruce Museum, the Clark Art Institute and the Currier Museum of Art. Each presents works on paper from the final decade of Lautrec’s brief yet prolific career and encourages visitors to reconsider the depth of his vision and his innovative approaches to portraying the Belle Époque.

Born into an aristocratic family in southern France, Lautrec discovered his muses and kindred spirits in the dance halls and brothels of Montmartre, Paris. There he’d sit, sipping his absinthe and sketching. He cut a quirky figure: a bespectacled lisper with a normal-sized torso and truncated legs that some have attributed to genetic inbreeding. He died of alcoholism at age 36. “His short life was a ‘burning bright’ situation,” said Samantha Cataldo, assistant curator at the Currier Museum.

The Paris of Toulouse-Lautrec: Prints and Posters from the Museum of Modern Art at the Currier (a traveling show with the Currier the final stop) features more than 100 pieces. Most are lithographs, dynamic and bold, many commissioned as advertising posters, such as the iconic Moulin Rouge, La Goulue, promoting the recently opened nightclub. The exhibition contains the entire Elles portfolio of 12 lithographs set in brothels. There is also an assortment of works of street vendors and ice skaters, people in parks and at racetracks. “He was observing all over Paris,” said Cataldo.

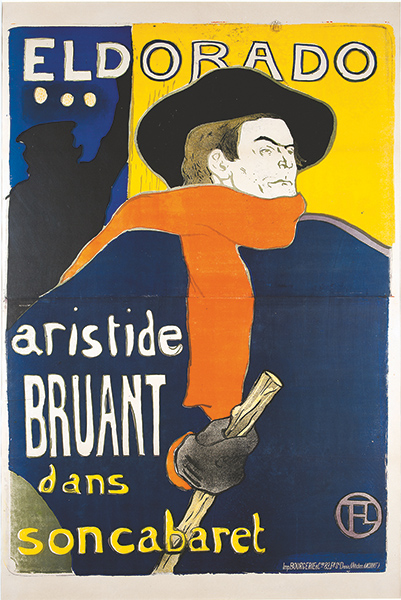

At the Bruce’s In the Limelight: Toulouse-Lautrec Portraits from the Herakleidon Museum, the roughly 115 prints, posters and drawings depict entertainers and other figures from Montmartre’s clubs (often made famous by Lautrec’s portrayals). The exhibition’s lens, explained Mia G. Laufer, the show’s guest curator, is “Toulouse-Lautrec’s relationship to portraiture and the cult of celebrity.”

The works are grouped by personalities, among them the can-can dancer Jane Avril, the singer Yvette Guilbert with her elbow-length black gloves and the cabaret owner Aristide Bruant, dashing in a wide-brimmed hat and red scarf. There is also a small selection of animal images.

“[Toulouse-Lautrec] creates a sense of intimacy,” said Laufer, “He’ll put a figure in the immediate foreground, which makes you feel like you’re there in the crowd.” All the pieces are from the collection of Paul and Anna-Belinda Firos, of Connecticut, who founded the Herakleidon Museum in Greece.

At the Clark, The Impressionist Line: From Degas to Toulouse-Lautrec showcases 40 prints and drawings by 15 impressionists who are better known for their paintings. “The show explores the different ways that artists were using prints and drawings for private and public reasons at a time when photography and photomechanical reproduction were changing the ways that images were understood,” said Jay A. Clarke, the museum’s Manton Curator of Prints, Drawings, and Photographs. “Our intention was to show the range of these artists and the amazing experimentation they were doing.”

Lautrec’s experimentation is evident in four lithographs, with their large swaths of color and oblique perspectives. Two whimsical drawings of circus acts were made shortly before his death, while he was institutionalized against his will. “He asked his friends to send him pencils and crayons,” said Clarke, “He always said that drawing brought him freedom.” The Impressionist Line was co-curated by the Clark and the Frick Collection, in Manhattan, and first shown at the Frick in 2013. All the works are from the Clark’s collection.

Commenting on the endurance of Lautrec’s oeuvre and legacy, Cataldo said, “[Toulouse-Lautrec] was a huge part of that storied era…and he produced so many of the images that represent it.” Those images pushed visual boundaries with their dramatic use of color and cropping. “Lithography was a new process, and he ran with it,” she said. Furthermore, his advertising posters were plastered all over the city: their vivid compositions were intended to lure audiences. “He was a master of grabbing the viewer’s attention,” she said.

Lautrec’s visual vocabulary not only influenced modern art and graphic design but according to Cora Michael, former curator

in the Department of Drawings and Prints at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, “It is fair to say that without Lautrec, there would be no Andy Warhol.”

As for the serendipity of three simultaneous New England exhibitions featuring Lautrec and the Belle Époque, Clarke acknowledged that each was years in the planning and their overlap was coincidental. Then she paused and added, “Maybe we should all be drinking absinthe now, like Toulouse-Lautrec.”

In the Limelight: Toulouse-Lautrec Portraits from the Herakleidon Museum. Bruce Museum, Greenwich, CT, brucemuseum.org. On view through January 7, 2018.

The Paris of Toulouse-Lautrec: Prints and Posters from the Museum of Modern Art. Currier Museum of Art, Manchester, NH, currier.org. On view through January 7, 2018.

The Impressionist Line: from Degas to Toulouse-Lautrec. Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, MA. clarkart.edu. November 5, 2017–January 7, 2018.

Image: Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Eldorado, Aristide Bruant dans son cabaret, 1892, color lithograph, 1380 x 960 mm. © Copyright Herakleidon Museum, Athens, Greece. Courtesy of the Bruce Museum.