Visual Weimar, 1919–1933

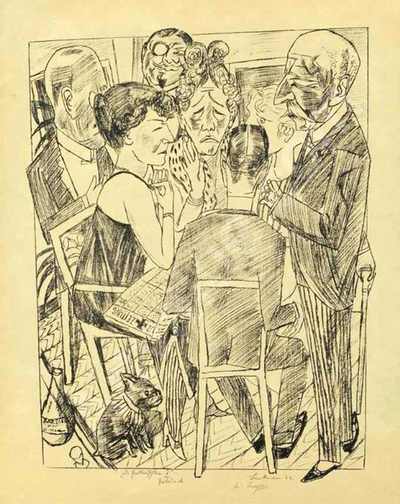

Max Beckmann, Die Enttäuschten I, 1922, lithograph, 19 1/3 x 14 4/5″. Courtesy of the Sabarsky Foundation.

Times of great social, economic and political unrest often produce some of the most radical advances in art and culture. Taiwan’s Chinese Cultural Renaissance, the May 1968 events in France, the US government-led Works Progress Administration and the street art and electro sha’bi of the 2011 Egyptian Revolution are moments of significant cultural awakening born by great turmoil. But none of these are as significant as the cultural production of post-World War I Germany. Between 1919 and 1933, as the price of a loaf bread rose a billion-fold and left- and right-wing groups battled for power, Germans embraced modernism and produced German expressionism, new objectivity, the Bauhaus, five Nobel prize winners and a host of advances in literature, dance, music and drama. While the Weimar Republic is a case study in post-war failed states, it is also an example of how in the rockiest soil, cultural advancement can take root and bloom.

Middlebury College Museum of Art provides a fresh, innovative peek at Weimar’s visual output in the well-done, student-curated exhibit, Visual Weimar, 1919–1933. Twenty-five works-on-paper are grouped thematically: everyday life, war and its aftermath, general conflict and entertainment, sexual fantasies and Bauhaus. While the woodcuts, lithographs and etchings represent a who’s who of notable Weimar artists—George Grosz, Max Beckmann, Otto Dix, Käthe Kollwitz, Erich Heckel and Lyonel Feininger—the works themselves are not particularly remarkable. But where the exhibition succeeds is the pairing of these works with student-made animations presented on iPads in the gallery (and also on the exhibition website). In the video accompanying Oskar Fischer’s lithograph Reitendes Paar, the artist’s abstract rendering of a riding pair is interrupted by Bauhausian shapes in their correspondent primary colors: blue circles, yellow triangles, red squares. In reference to Otto Dix’s etching Billiardspeiler, which shows five gentlemen playing pool in a bar, a video by the same title brings the piece to life by adding dialogue that speculates about what these men may have been saying to each other. The result is a smart exhibition that uses the artwork to develop a deeper understanding of the past and, as a result, a much deeper appreciation for the artwork.