Distributions and Reanimations: Report from dOCUMENTA (13)

By Rebecca Uchill

During the closing week of dOCUMENTA (13), visitors found the following announcements posted throughout streets and transit stations: Documenta: An Art Exhibition in Kassel, Germany—as if any reminder were necessary in the context of an exhibition that had taken over the city center. Beneath that header, the posters went on to advertise less immediately evident engagements of the 2012 Documenta franchise further afield: And in Kabul. And in Cairo. And in Banff.

Joan Jonas, Reanimation, 2010–12. Photo: Nils Klinger.

dOCUMENTA (13) was widely distributed on many fronts. As advertised, the exhibition was simply expansive in its sheer geographic reach: for example, an associating series of seminars and an exhibition in Kabul ran through spring and summer of 2012, and an August retreat at Canada’s Banff Center invited applicants to join d(13) collaborators in considering the very practice of retreat. The exhibition and programs were equally broadly distributed in terms of their disciplinary and temporal scope: Artistic Director Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev’s exhibition was not delimited to contemporary art; instead, it also encompassed aspects of culture ranging from ecopolitics to history. This year’s iteration also pushed the exhibition’s characteristic 100-day timeframe, offering nearly hourly lectures, workshops, performances, demonstrations and activities for the full duration of the show, plus additional events and formats (i.e. the Kabul seminars, a series of commissioned publications) that extended the normal exhibition parameters. No visitor could be expected to see the entirety of d(13).

Orangerie, Documenta. Photo: Nils Klinger.

Christov-Bakargiev cultivated distributed agency as a related strategic process of exhibition research and administration, recruiting a group of curatorial “agents” and a transdisciplinary committee of advisors that included artists (i.e. Pierre Huyghe) inasmuch as critical theorists (i.e. Michael Taussig, Donna Haraway) and scientists (i.e. Anton Zeilinger). Many of this group also made specific contributions under their own names that could be encountered directly by visitors to the exhibition: Huyghe with a ponderous clearing in the park populated by sculptural, landscaped, and living beings, Taussig with the first in a series of dOCUMENTA (13) “notebook” publications, Haraway (less directly) having inspired a “Worldly House” archive of artists’ works on the intersections between nature and culture, and Zeilinger with a team presenting ongoing quantum mechanics demonstrations in the Fridericianum venue.

Jeronimo Voss, Eternity through the Stars, 2012. Photo: Nils Klinger.

Christov-Bakargiev ‘s team process, recalling the expansive curatorial project overseen by Okwei Enwezor in Documenta 11, attempts to eschew the lone curator mythos that has tended to float over Documenta since Harald Szeemann’s Documenta 5 in 1972. (Szeemann’s was the first in this recurring Kassel exhibition series overseen not by committee but by a guest curator; accordingly, Szeemann took the title Gastarbeiter, a word used to describe an itinerant or migrant worker).

In 2012, dOCUMENTA (13) celebrated its collaborative productions and hybrid engagements by listing all participants equivalently on its website: exhibiting artists, curators, biologists and other categories of engagers residing together in one alphabetical list. An associating “log book” published by Hatje Cantz discloses hundreds of emails between the curatorial agents, artists and other interlocutors, casting the production of the exhibition’s programs, texts and concepts as a multitudinous thinking process.

The comparison with Szeemann’s moment also allows us to see how the stakes of Documenta’s thematics have shifted. Werner Haftmann, one of the orignal exhibition overseers, left Documenta’s curatorial committee in 1967, in a resignation that historian Walter Grasskamp later characterized as an attempt to withdraw “before Pop art and photorealism could ruin the concept in which Haftmann in particular had invested his reputation: abstract art as world language.”1 Had Haftmann objected to bringing less utopianist artistic positions into the 1968 exhibition, he would not likely have been pleased with the thematic rubrics under which Szeemann conceptualized the 1972 Documenta in his own preparatory schematics. Sections were dedicated to such unlofty themes as “Advertising,” “Science Fiction,” “Political Propaganda,” and “Trivial Realism and Trivial Emblematics,” for example.2 This is to say that Szeemann’s 1972 Documenta departed from the apolitical promotion of universal culture common to earlier versions of the exhibition, instead featuring direct and individualistic engagements with the surrounding social context, as manifested in works such as Joseph Beuys’ overtly political office for Direkte Demokratie durch Volksabstimmung and Hans Haacke’s Besucherprofil, which surveyed visitor demographics.

AND AND AND, commoning in kassel and other proposals towards cultures of common(s), revocation,and non-capitalist life, 2010–12. Photo: Nils Klinger.

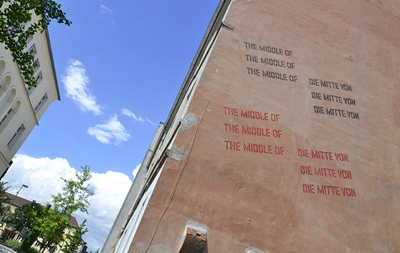

The axes of the 2012 Documenta conversation seem to realign. No longer do the romantics of socially disengaged globalism and the heroics of specific virtuoso statements pose a relevant dichotomy. It follows that Christov-Bakargiev and company’s “worlding,“ a notion drawn from Haraway, is neither an attempted universalizing project nor an individualizing one. Exhibition contributors engaged in creating alternative forums for pedagogical or political engagement—such as the AND AND AND collective with their co-habiting and co-learning series—are not at all concerned that positioning a critical public meeting grounds in the context of a major international exhibition is tantamount to (or mistaken for) social withdrawal. Instead, as Lawrence Weiner also seems to suggest in his exhibition contribution, this exhibition forwards the idea that it is through acts (and not placements) of localization that centers are created. This allows one to work contextually, and collectively to position oneself in the middle of the middle of the middle (of).

Lawrence Weiner, THE MIDDLE OF THE MIDDLE OF THE MIDDLE OF, 2012

From the standpoint of production and reception, what the expansive programmatic plan entailed was dOCUMENTA (13) occupying exhibition halls (in museums, as well as parks, way stations, a hospital, a bunker, and many small structures erected for single artists’ and collectives’ projects) inasmuch as lecture halls, auditoriums, conversation spaces, ersatz laboratories, therapeutic workshops and a series of publications. The durational programming had an added boon for the tourist industry. The front page of the Hessische Allgemeine on its final weekend proclaimed “dOCUMENTA (13) Breaks All Records: Guests stay longer—fifty percent more hotel bookings as in 2007”! Given the extensive calendar of events, these guests were doubtless rewarded for their extended visits. In a five-day stay, I was treated to a choreographed performance by Jérôme Bel, a lecture by Franco ‘Bifo’ Berardi, and a fabulation/tour by Walid Raad. I was also a participant/subject in a group hypnosis session led by Marcos Lutyens as well as one of artist Stuart Ringholt’s Anger Workshops. All were offered as part of the exhibition’s regular public offerings.

Stuart Ringholt, Anger Workshops, 2012. Photo: Nick McGrath.

Readers of Art New England will take particular interest in Joan Jonas’s performance also presented during the closing week. The piece developed in part out of her work with pianist Jason Moran during his MIT residency in 2011.3 The performance was held in the Kaskade Cinema, a postwar construction by the Kassel architect Paul Bode (and brother Arnold Bode, a member of Documenta’s founding leadership). For 2012, the abandoned theater was rehabilitated and returned to public use. Jonas’s coincidentally titled Reanimation featured the veteran performance artist’s video, dance, and live drawing—abstracted riffs on themes of glaciers and snow, with much text coming from Nobel-prize winning Icelandic novelist Halldór Laxness’s Under the Glacier.

Moran’s keyboard responses to Jonas’s visual and textual presentations were occasionally familiar from the lecture-demonstration presented last fall in Boston, but the 2012 Kassel version incorporated new music, as well as a much larger amount of text, new abstract video of snow shot in Norway, and generally faster pacing. A particularly compelling moment of the performance came when Jonas held a large piece of paper over her body and rapidly drew its contours, dancing with this abstracted body held tightly to her.

Joan Jonas, Reanimation, 2010–12. Photo: Nils Klinger.

Reanimation also had a second instantiation in the exhibition as an installation in the Karlsaue Park by the title Reanimation (In a Meadow). There, Jonas constructed a four-sided structure with large windows open for public viewing from the exterior. Through the structure’s windows the audience encountered video, text and objects from the performance, set up in four vignettes. Even absent of Jonas’s presence, the performance props served to activate the videos further. These included prisms catching and reflecting sunlight and drawings propped in the windows or laid barely in the line of vision on the floor, prompting closer looking. In both instantiations of Reanimation, a particular quote from Laxness stood out: “One can be one’s own ghost and roam about in various places, sometimes many places simultaneously. Perhaps I didn’t approach it quite correctly. A ghost is always the result of botched work; a ghost means an unsuccessful resurrection, a shadow of an image that has perhaps once been alive, a kind of abortion of the universe.”

Tempting as speculation is, in the end neither of the components of Reanimation appeared as an attempted resurrection of the other, botched or otherwise. With the inversion of the normative exhibitionary timeline (presenting an installation based on a performance to occur in the future), each of the two works felt independent but linked, enigmatically referencing each other.

As the exhibition at large repeatedly suggested—distributed sites, multiform incarnations, agents and subjects, contemporeneity and history—all of these propositions are interconnected, without clear hierarchy. dOCUMENTA (13) asked what might result from claiming a large field of political, scientific and aesthetic knowledge as co-habitants within the same exhibition platform, and in so doing, embrace its own resultant geographic, disciplinary and thematic sprawl.

Rebecca Uchill is a curator and art historian, based in Boston. She is a PhD candidate at MIT’s Department of Architecture, in the History, Theory, and Criticism of Art and Architecture discipline group.

1In Thinking About Exhibitions. Reesa Greenberg, Bruce W. Furguson, Sandy Naime, eds. 1996: Routledge, London, p. 54.

2Documenta archives: Mappe 115, 19. 5. 1972

3Other dOCUMENTA (13) projects with ties to recent Boston-area engagements included Florian Hecker’s sound installation, also developed during a visiting artist residency at MIT, and William Kentridge’s installation, including video materials he presented in his 2012 Norton Lectures sponsored through The Mahindra Humanities Center at Harvard.