Thoughts on encountering paintings by Jim Peters, Figurative Revisionist

By Susan Rand Brown

For a painter like Jim Peters, “on the scene” in galleries and museums since the late 1970s, to have his art ignored—that is, seen but not seriously considered—would be cruel punishment. No need to worry. His paintings have never been wallflowers. Peters’ figures are hard to ignore, even as acolytes, questioning or straddling the fence. They are women and men, positioned in the dingiest of (bed)rooms, windows darkened and seemingly blocked, where they read and lounge pre- and post-coitus—the aureole around which Peters’ coal-dark scenarios revolve.

Given the postcard-like work that flourishes in summer galleries like so many Cape Cod cottages in July, the two Jim Peters exhibitions in Provincetown’s East End right now, the retrospective curated by John Wronoski at the Provincetown Art Association and Museum (through August 11) and the other at the artSTRAND Gallery (through August 7) speak highly for the future of serious painting, and are worth viewing and discussing: shake ‘em up, Jim.

Jim Peters installation. Photo by James Zimmerman,

In addition to his paintings, which combine elements like wood, metal and glass, he also builds wall-mounted, three-dimensional constructions, theatrical tableaus of lust and longing. Photographs by Kathline Carr, his wife and collaborator, have recently replaced the painted figure and serve to make the image more mysterious, forbidding, and hard to consider for painterly qualities alone (for we are all implicated as voyeurs in Peters’ world).

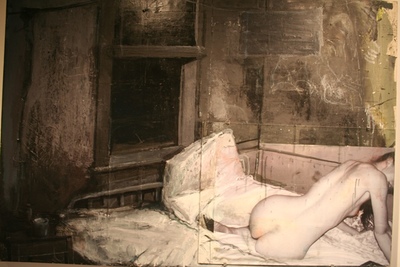

There is Black Window, 2010, oil on canvas, glass and collaborative photograph, 60 x 72”, which we are asked to view (museum label) as “among Peters’ most successful experiments with integrating photographic elements into his painting”: the darkened window is there, but what catches the eye is the figure, a photograph positioned in the foreground a little off-center, head cropped above the mouth, the inverted V at the tip of her pear-shaped posterior tinged a soft ruby red. Let’s agree that this figurative collage, in its use of shallow space, fits squarely within the history of western art. But is that all there is?

Jim Peters, Black Window, 2010, 60 x 72″, oil on canvas. Collaborative photograph between Kathline Carr and Jim Peters. Photo courtesy of Annie Longley.

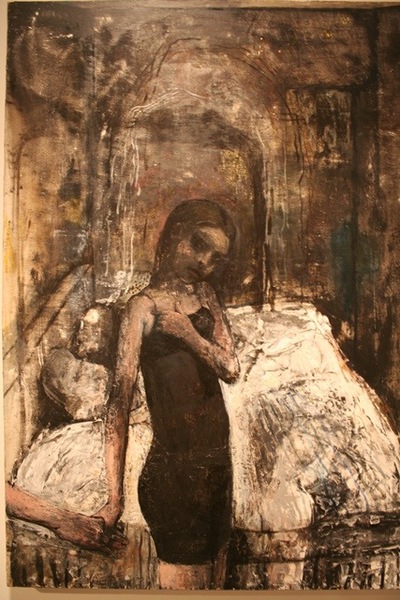

In The Invitation, 1989, oil on canvas, 43 x 36”, collection of Heide Hatry, New York, we see a young woman fingering the strap of her black shift (a slip?), eyes blackened, hair stringy. She stands before a grimy mattress; her small hand is gripped by one belonging to an older man. The museum label prompts this understanding: “The Invitation was part of a series of paintings set in a small room or alcove big enough only for a mattress, an exploration of the idea of containment, or alternately, the sufficiency of small spaces … The setting, like many of Peters’ rooms, is a sort of small stage, and the action it implies, as in much of the work, is the result of the artist’s manipulating of characters in rapidly mutating imaginary scenarios.”

Jim Peters, The Invitation, 1989, 48 x 36″, oil on canvas. Collection of Heide Hatry NY, NY. Photo courtesy of Annie Longley.

And what of these “rapidly mutating imaginary scenarios?” What is being implied? Have we moved so far into the realm of post-structuralism that the only “scenario” worth noting is an abstract idea (“containment”) and not the implications emanating from the staged drama itself, the “containment” or entrapment of the legions of teenaged girls who end up mutilated, wrapped in sheets and buried in basements?

None other than Willem de Kooning famously remarked, “Flesh is the reason oil paint was invented,” and Peters too readily acknowledges, in discussion and in his work, a continuing fascination (obsession) with the female figure. The clarion calls surrounding de Kooning’s expressionist studies of female figures have receded into a faraway past. It was a more innocent time, when art, and literature, were being discussed for content without embarrassment, as made clear by de Kooning’s hugely successful Museum of Modern Art retrospective (2011), where once controversial paintings of fire-breathing women have been enshrined as icons of American (and international) art. Jim Peters may well enjoy a career trajectory similar to de Kooning’s. Meanwhile, this reviewer will continue to admire the art, while still puzzling over the absence of a broader consideration of its figurative content.

Jim Peters installation. Photo by James Zimmerman.

Visit Jim Peters Curated by John Wronoski at www.paam.org and New Works by Jim Peters at www.artstrand.com.