America in Transition

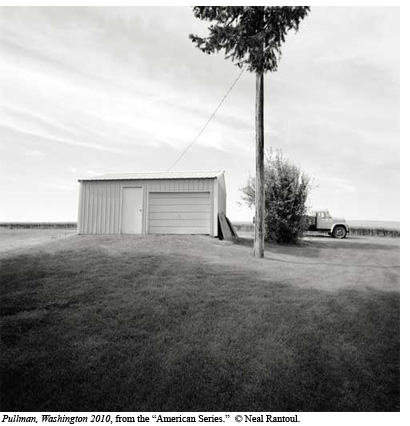

Ribbed patterns of wheat, like corduroy, cover the broad, rolling land near Pullman, Washington. Neal Rantoul’s Pullman, Washington, 1996–2001, is a series of photographs that explore this territory with straightforward visual clarity, honoring the formidable scale and visual depth of the land while making it accessible. Rantoul’s exhibition at Panopticon is a survey of a number of his serial black-and-white projects done over a period of twenty-five years.  Rantoul, who has been head of the photography program in the Department of Art and Design at Northeastern University since 1981, has built a substantial body of work with roots in American photographic landscape traditions and the lean aesthetic of photographers like Harry Callahan and Frederick Sommers.

Rantoul, who has been head of the photography program in the Department of Art and Design at Northeastern University since 1981, has built a substantial body of work with roots in American photographic landscape traditions and the lean aesthetic of photographers like Harry Callahan and Frederick Sommers.

The exhibition is a narrative journey through parts of the American landscape, emphasizing the edges and borders that exist between the manmade and natural. Moving examples of this dichotomy exist in his series Oakesdale, Washington, 1996. The Oakesdale pictures, made in the second year of the eastern Washington wheat fields project, introduce the modest structures and plantings of rural cemeteries, placed in the foreground against the open land of the wheat fields. Gravestones, monuments, and trees rise vertically against the rolling fields, their alignments measured.

Rantoul’s photographs do not rely on the typically celebrated views; they do not expose great moments. Often plainly frontal and tonally subtle, the pictures inform far more than would be assumed about such ordinary scenes. In his series Yountville, California, 1982, modest homes exist as small evidence of persistence within tangles of trees and overgrowth, framed behind bulky roadway guardrails. The environment, which we now understand is fragile, is tenacious here, darkly encircling the houses just as the roadway splits. These pictures make dual claims of power between ourselves and our mediated geography.

Rantoul’s photographs do not rely on the typically celebrated views; they do not expose great moments. Often plainly frontal and tonally subtle, the pictures inform far more than would be assumed about such ordinary scenes. In his series Yountville, California, 1982, modest homes exist as small evidence of persistence within tangles of trees and overgrowth, framed behind bulky roadway guardrails. The environment, which we now understand is fragile, is tenacious here, darkly encircling the houses just as the roadway splits. These pictures make dual claims of power between ourselves and our mediated geography.

Rantoul has photographed new housing projects in Atlanta that present the constructed landscape as earnestly clean, as though its sparkling new geometry makes it certifiably viable. The photographer turns that coin over in two different series of architectural investigations. The most recent, Old Trail Town, Cody, Wyoming, 2005, is about a curious fiction of a town made of “found” buildings brought to Cody and assembled as a tourist attraction of the supposed Old West. As hokey as the idea might sound, Rantoul’s photographs offer a precise angularity that highlights the dry age of the buildings’ materials. The subject’s theatrics is mostly a curiosity because the photographs draw us not to that posed town, but to the structures themselves. Their hard use reflects the dignity of the plain land upon which they have resettled. Rantoul is fond of the direct, nearly symmetrical image, the flatness of a wall parallel to the picture plane. This economic ordering of space reduces narrative play. Structures sit clad in their brittle planks and clapboards with few windows—centered, proper, and raw. They have been transformed by weather more than by use, as though the job of architecture is to wait for the hollowing out of abandonment. It is fitting that these particular structures have themselves abandoned their original sites. Perhaps this is the occasional disorientation of history.

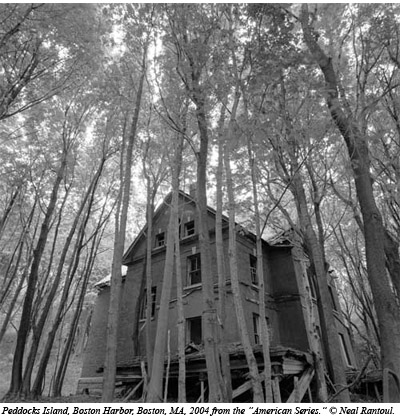

The series Peddocks Island, Boston Harbor, Boston, Massachusetts, 2004, records another abandonment in its original setting. Peddocks Island, which is just across from Hull, had been settled as a farming community early in the seventeenth century. During the Revolutionary War, militiamen were stationed on the island and in 1904, Fort Andrews was built, which served as harbor defense through World War II. A number of the original fort buildings still stand as well as military housing. Although a few private cottages remain in use on the island, it has been part of the Boston Harbor Islands National Recreation Area since 1996. Rantoul’s photographs include the military housing structures in an area closed off from the public for safety reasons. In this desolate space the land slowly reclaims what was left behind. History is seen in a slow dissolve. The photographs do more than document the transition. Dark windows suggest interiors of constant night. As eyes they are blind, as mouths they are awful maws. This anthropomorphic face reading is hard to resist—houses do have façades—and it’s harder still not to be moved by them. The houses become debris, derelict, and empty, their purpose stripped away.

The series Peddocks Island, Boston Harbor, Boston, Massachusetts, 2004, records another abandonment in its original setting. Peddocks Island, which is just across from Hull, had been settled as a farming community early in the seventeenth century. During the Revolutionary War, militiamen were stationed on the island and in 1904, Fort Andrews was built, which served as harbor defense through World War II. A number of the original fort buildings still stand as well as military housing. Although a few private cottages remain in use on the island, it has been part of the Boston Harbor Islands National Recreation Area since 1996. Rantoul’s photographs include the military housing structures in an area closed off from the public for safety reasons. In this desolate space the land slowly reclaims what was left behind. History is seen in a slow dissolve. The photographs do more than document the transition. Dark windows suggest interiors of constant night. As eyes they are blind, as mouths they are awful maws. This anthropomorphic face reading is hard to resist—houses do have façades—and it’s harder still not to be moved by them. The houses become debris, derelict, and empty, their purpose stripped away.

Another series of photographs, Escalante, Utah, 2001, reveals a raw, natural world without human intervention. In this project Rantoul presents the time-shaped world of canyons, buttes, and stone in forms that evoke bodies—even human bodies. These rockscapes are impenetrable, indifferent to our passing. They stretch and contort in motions so slow they are measured in eons. Because these pictures are within this overall project, we may be forgiven the impulse to read them as familiar—as in family—forms, as being somehow like us. The Utah pictures are surely of a silent and still earth, yet an earth acted upon, an earth shaped by water, wind, erosion, and even its own weight. It is an earth in transition, always forming and un-forming. Similarly, the transitional borders that Rantoul’s manmade environment present are part of the discourse of our settlements and our territorial claims. Both take on the patina of who we are and who we have been.

That Rantoul’s photographs build on a minimalist approach does not hinder our attachments to the land and what we make of it. The photographs do not, in the minimalist art manner, assert a blank object-ness. Rantoul’s vision is coolly reserved, but it makes no hard claim against analogy or meaning. There is a quirky willingness on his part to photograph anything according to the circumstances in which it is found. Circumstances are as plain as a strange sky, as curious as the pattern of growing grass, and as casually mute as a coiled hose or a crumbled roof.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________

David Raymond is a sculptor, painter, poet, and professor of fine arts at Merrimack College in North Andover, MA, where he is also the director of the McCoy Gallery.