Do It Yourself: Michael Oatman

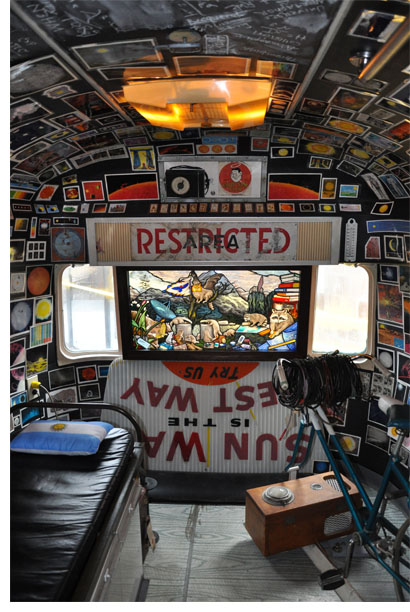

What is that? As a response to a curiously modified Airstream trailer with collapsed parachutes hanging from it, perched atop what was the former factory power plant at the edge of MASS MoCA, there is nothing surprising about this question. For Michael Oatman, the artist responsible for the work, this note of puzzlement is both an invitation and a liberation. The experience of completing this largely covert four-year project freed him to acknowledge what he had made—a mystery. As he said in a recent conversation, “It’s interesting working on a secret, but after a while you want to tell somebody.”

What is that? As a response to a curiously modified Airstream trailer with collapsed parachutes hanging from it, perched atop what was the former factory power plant at the edge of MASS MoCA, there is nothing surprising about this question. For Michael Oatman, the artist responsible for the work, this note of puzzlement is both an invitation and a liberation. The experience of completing this largely covert four-year project freed him to acknowledge what he had made—a mystery. As he said in a recent conversation, “It’s interesting working on a secret, but after a while you want to tell somebody.”

The question at the beginning of any encounter with All Utopias Fell is also an invitation. “When I make stuff, I want my viewers to have the same experience I have when I’m a viewer,” Oatman insists. This means having the audience “really being drawn into the world” of what he has fashioned. But this does not mean simply working out the puzzle of the author’s understanding. Quite the opposite. Oatman invites the possibility that strangers can “have better experiences than I do when they come in here.”

There is a generosity—and a democracy—to what Oatman offers. He certainly welcomes questions about how it’s made, as long as the larger narrative doesn’t suffer. Part of the excitement of the piece is the surprise. Thus, a detailed map could be a spoiler. Instead, the work is meant to be unexpected and full of wonder and not simply reducible to its constituent parts. As Oatman contends, “There is nothing essential about my work.” In fact, there’s not a single element so crucial that if overlooked would forfeit complete understanding.

There are no better answers to the viewer’s questions about this than whatever narrative the viewer fashions. Anyone who opens the door of what turns out to be a handmade spaceship is more than a witness to the work, but a collaborator. Oatman’s creation is not a fantasy, but a reality on its own terms. It demands a suspension of disbelief on the same level as any literary fiction.

While Oatman loves to make things, he does not contrive them merely for the sake of how they look. Although he began as a painter, he gave up “sitting in front of a white canvas and creating it all from scratch.” Rather, he’s a

storyteller making a novel out of objects. Everything in his work has some significance, yet there’s not one object that unlocks the key to meaning. Each piece is a part of what tricks us into credulity.

Oatman plays the trick on himself as well. The story he fashions with the piece is a story about the person who he imagines built it. As Oatman describes, he “became this character…Donald Carusi, vernacular rocket builder” and made the work as Carusi would have. This is more than simply assuming an alter ego for the purposes of performance. He had “to get into the mindset of this guy building the ship” because he actually had to build it…”

As deeply as he’s involved in the fiction—he readily admits the important intersection of his biography with the objects—it is clear how much Oatman now looks forward to what happens in his absence. His willingness to remove himself is part of the gift the work gives to its audience. The real resonance of the piece lies not only in the story Oatman tells for himself, but in the manifold other stories he makes possible for each person who encounters it.

As deeply as he’s involved in the fiction—he readily admits the important intersection of his biography with the objects—it is clear how much Oatman now looks forward to what happens in his absence. His willingness to remove himself is part of the gift the work gives to its audience. The real resonance of the piece lies not only in the story Oatman tells for himself, but in the manifold other stories he makes possible for each person who encounters it.

As has been the case with a number of his earlier installations, Oatman notes that “things happen to them—things get stolen, people leave stuff…begin to claim it, somehow incorporate it into their history of being a viewer.” Rather than resent these alterations, Oatman has accepted them, convinced that “whatever people bring in becomes part of its story” making it even better.

This selflessness is not without its humorous side. There is a great deal of laughter within the marvel of the work, with Oatman himself remembering cracking up occasionally as he made it. Given that the vehicle contains rows of mason jars filled with preserved tomatoes and a complete Richard Brautigan story embossed on narrow plastic tape outlining the entire interior, the jokes are obviously not all private.

If we are invited to imitate the artist laughing, we are also given an even greater responsibility. It does not take long to realize that no single viewing of this intricate fiction could ever be complete. But that serves as a source of delight rather than frustration. Before my daughter and I passed through the door of the ship, Oatman declared, “Probably the best way to see it is without somebody talking.” He meant, of course, that it would be best if he didn’t talk, giving all the glossary and keys he alone could provide. He trusts his own work, confident that it says something on its own. And when he made the magnanimous gesture of letting us enter by ourselves, he entrusted the piece to our imagination, as he offers it to the imagination of everyone who follows. As we went in, Oatman said simply, “It’s all up to you.”

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Stephen Vincent Kobasa is a political activist, poet, and curator, as well as a contributing editor for Art New England. His reviews have also appeared in Big, Red, and Shiny and the New Haven Independent, among other places.