Dynamic Invention

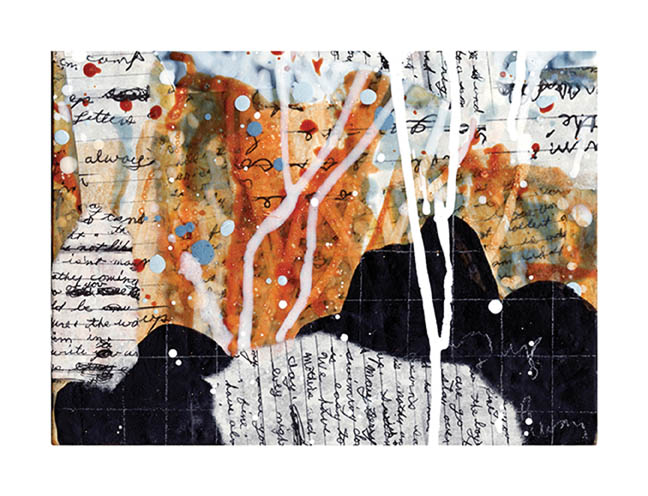

Nancy Manter, Every Night, 2012, archival inkjet, 9 x 12.5″.

American Abstract Artists (AAA) is celebrating its 75th anniversary in a big way. As a small, nervy group in 1936—led by such figures as painter George L. K. Morris, muralists and WPA leaders Ilya Bolotowsky and Balcomb Greene, and sculptor Wilfred Zogbaum—they challenged Alfred Barr and The Museum of Modern Art to include Americans as well as Europeans in MoMA’s first major survey of abstract art. Since its founding, AAA embraces more than 330 artists. Over the past two years, works have filled nine exhibitions across the United States as well as in Otranto, Italy, Paris, and Berlin. The latest of these presents a groundbreaking print portfolio featuring work by 48 leading artists. It is on view through October 20 at the Brattleboro Museum & Art Center in Vermont, the first stop on a nationwide tour organized by the University of Tennessee, Knoxville.

Proving that AAA is still a nervy bunch, the exhibition, three years in the making, showcases the organization’s first digitally produced portfolio, striking a new aesthetic level for digital printmaking technology and serving an encyclopedic range of vivid abstract imagery, while also challenging long-lived notions about what is fine art and what is commercial.

“This marks both a technical and conceptual shift in printmaking. Our choice of medium situates this portfolio squarely in the 21st century and is an indication of the group’s forward momentum,” declares Daniel G. Hill, portfolio project director and AAA president, in a statement describing the project. Technically, this is far from commercial giclée inkjet technology, and the creative process is vastly different. Each artist was asked to provide a digital file meeting predetermined portfolio specifications, but with no restrictions on how the file could be created. The digital process could include scanning of flat-work made expressly for the project, digital compositing and image manipulation, as well as the use of vector-based software and hand-coded algorithms. “The results are as varied as the artists’ individual sensibilities,” says Hill.

Hill has been experimenting with fine art digital image-making for ten years, pursuing ways to use photographic and digital technology as part of an intuitive creative process. In an interview with Réalités Nouvelles, an organization of French abstract artists, he challenged his audience to see abstraction as “a thought process that is not anchored to any particular medium or method. A diversity of outcomes needs to be embraced if abstraction is to remain relevant and not appear to have been an historical aberration.”

Nonetheless, doubt about the artistic value of digitally created prints remains strong among many artists, curators, and critics. “I’ve always loved American Abstract Artists, but I was skeptical about anything involving inkjet printing,” said Brattleboro’s curator Mara Williams. “Because I was trained in the seventies and eighties, the craftsmanship of really terrific printmaking is very exciting to me. With digital technology, the focus is on the image quality itself, and the results here are just staggeringly good.”

The portfolio’s modest dimensions of 9¾ by 12¾ inches requires close looking, and each work rewards in unique ways. Dan Hill’s illusion of rolling surfaces and shifting light inspires meditation, while Gail Gregg’s Delicious knits together multiple layers of imagery until they seem to rise off the page. The thick textures and rich color of oil-stick drawing seem fully palpable in Thornton Willis’s Untitled abstraction, and the multiple media of paint, paper, and pattern in Nancy Manter’s Every Night offers the complexity of a master silkscreen. As Robert Storr, Dean of Yale University School of Art, writes in his introduction to the show, “What binds past and present members of AAA together is a deep respect for the value of visual experience unencumbered by programs and pretensions.”

“For me as curator,” Williams confides, “it’s a wonderful overview of abstraction because everything you could possibly want is here. Each work becomes an object of contemplation, and every nuance of that image is yours to enjoy, to notice, to comment on with your head, your spirit and heart, your whole being.”

Bonnie Barrett Stretch is a longtime writer and editor for a wide range of art publications. She writes frequently for Art New England and is a contributing editor of ARTnews