Edward Gorey’s Elegant Enigmas

The men in Edward St. Jean Gorey’s drawings often wear long fur coats, as Gorey himself habitually did. The women sometimes wear black veils, as if in mourning. The children tend to carry dead-looking dolls and ride frail-looking bicycles. In Gorey’s world hardly anyone smiles. His characters typically wear expressions that are stunned or even comatose. Viewers of his work, though, often smile, if somewhat uneasily. His work is about horror but it’s also hilarious. Sort of. In truth, it’s impossible to pin it down, which is, of course, part of its fascination. Even his interiors and gardens are unsettling. A chasm appears in a floral carpet, opening like a miniature Grand Canyon. An unkempt topiary sprouts unruly sprigs and looks ready to attack.

The men in Edward St. Jean Gorey’s drawings often wear long fur coats, as Gorey himself habitually did. The women sometimes wear black veils, as if in mourning. The children tend to carry dead-looking dolls and ride frail-looking bicycles. In Gorey’s world hardly anyone smiles. His characters typically wear expressions that are stunned or even comatose. Viewers of his work, though, often smile, if somewhat uneasily. His work is about horror but it’s also hilarious. Sort of. In truth, it’s impossible to pin it down, which is, of course, part of its fascination. Even his interiors and gardens are unsettling. A chasm appears in a floral carpet, opening like a miniature Grand Canyon. An unkempt topiary sprouts unruly sprigs and looks ready to attack.

In his lifetime (1925–2000), Gorey wrote and illustrated more than 100 books with such titles as The Loathsome Couple, The Fatal Lozenge, and The Hapless Child. He became a cult figure. His widest audience to date is all those who watch the PBS series Masterpiece Mystery. His animated art graces the credits with swooning maidens and falling urns. His fans hereabouts will, I predict, be delighted with Elegant Enigmas: The Art of Edward Gorey, now at the Boston Athenæum.

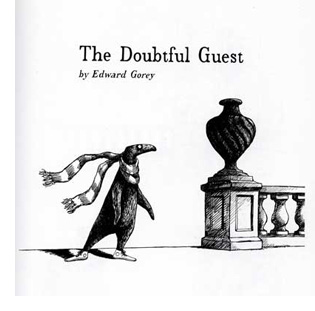

The Doubtful Guest Stuffed Toy opens the show. The toy looks bedraggled and dubious indeed. (Gorey himself sewed his toys.) One of the two figures in it looks half-human and half-something else. Maybe an anteater? It has four arms, ending in claws. While it (he?) is properly dressed, in an Edwardian high-collared shirt and tie, if this creature showed up at your door any day save Halloween, you’d probably call 911.

The earliest works in the show date from the 1950s, when Gorey was fresh out of Harvard, his years there having been delayed by a compulsory Army posting at the Dugway Proving Ground in Utah, where, he would tell interviewers, 12,000 sheep were later found mysteriously dead. It sounds like something he’d write about. Although his only brush with formal art training was one course at the Art Institute of Chicago as a youth (he was born and raised in Chicago), even in the ’50s his mature style was present. The Athenæum show makes it clear that Gorey didn’t evolve as most artists—not something most devotees would have wanted of him. His technique was phenomenal. He drew to the scale of his tiny books, generally four by five inches. He usually drew in pen, ink, and watercolor. Color is relatively rare in his work, as if it were somehow too jolly.

One early work, The Unstrung Harp; Or, Mr. Earbrass Writes a Novel (1953) is a delicious sequence of non sequiturs, starting with Earbrass playing a harp with no strings and moving onto a solo game of croquet before he gets down to the business of writing and the torture of rewriting. This last process shows him sitting on the floor with a decanter of sherry beside him, tossing unsatisfactory pages into a wastebasket. If you peer out the window, there is either a hot air balloon or a parachute. It’s so infinitesimal it’s impossible to tell which.

Gorey liked illustrating the alphabet. The page devoted to E in The Glorious Nosebleed: Fifth Alphabet shows a glum family trudging through a winter day wearing mufflers that look ready to trip or strangle them all. The line of text, “She knitted mufflers Endlessly,” suggests a woman who is a version of Madame Defarge, knitting scary scarves that render a guillotine unnecessary.

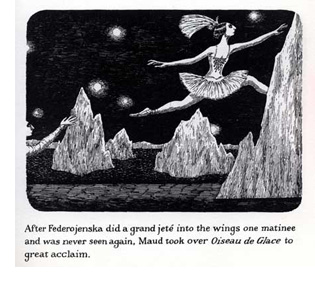

The more you know about one of the subjects that interested Gorey—be it Victorian literature, opera, Edwardian dress and décor, or ballet—the more you will love this show. Gorey was an ardent balletomane who, for season after season, attended every performance of New York City Ballet, including forty or so consecutive Nutcrackers. His two books on ballet—The Gilded Bat and The Lavender Leotard—contain references to “George” and “Lincoln,” City Ballet co-founders Balanchine and Kirstein, to a ballet called Oiseau de Glace, a play on Firebird, to a ballerina called “Federojenska” who did a grand jeté into the wings at one performance never to be seen again. (There’s no shortage of crazy Russian ballerinas in the annals of dance history, but one possible model for Federojenska is Olga Spessivtseva, who spent a couple of decades in mental institutions.) Federojenska is replaced by a hard-working young dancer named Maud, who becomes a star. But the line “her life was really no different from what it had ever been,” accompanies an illustration of the drudgery of the daily barre.

The more you know about one of the subjects that interested Gorey—be it Victorian literature, opera, Edwardian dress and décor, or ballet—the more you will love this show. Gorey was an ardent balletomane who, for season after season, attended every performance of New York City Ballet, including forty or so consecutive Nutcrackers. His two books on ballet—The Gilded Bat and The Lavender Leotard—contain references to “George” and “Lincoln,” City Ballet co-founders Balanchine and Kirstein, to a ballet called Oiseau de Glace, a play on Firebird, to a ballerina called “Federojenska” who did a grand jeté into the wings at one performance never to be seen again. (There’s no shortage of crazy Russian ballerinas in the annals of dance history, but one possible model for Federojenska is Olga Spessivtseva, who spent a couple of decades in mental institutions.) Federojenska is replaced by a hard-working young dancer named Maud, who becomes a star. But the line “her life was really no different from what it had ever been,” accompanies an illustration of the drudgery of the daily barre.

One inevitable frustration of the show is that only select scenes from the books are included. To see the whole book, you have to buy it. Gorey expert Karen Wilkin has written the text for the exhibition catalogue, a fine addition to this traveling show organized by the Brandywine River Museum in Pennsylvania. Another reading recommendation: the profile that erstwhile Boston Globe music critic Richard Dyer wrote in the newspaper’s Sunday magazine on April 1, 1984. (Was the April Fool’s Day publication date an accident?)

The Athenæum is the perfect place for a Gorey show, and not just because the institution combines literary and visual arts. The gallery is now on the ground floor, but years ago it was upstairs, where visitors could spy members who looked as if they’d been sitting in the same place for decades, ripe for a Gorey illustration.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________

Christine Temin was the art and dance critic at the Boston Globe for over two decades and now writes for a variety of international publications. She has taught at Middlebury College, Wellesley College, and Harvard University. Her most recent books is Behind the Scenes at Boston Ballet, published by the University Press of Florida.