Emerging Trends in the Museum World

Neil Harbisson “listening” to color with his surgically-implanted antenna. Photo: Lars Norgaard.

Museums are sometimes accused of focusing too much on the past. We preserve and conserve collections. We love retrospective exhibitions. We revel in historical minutiae.

But once a year we indulge ourselves a glimpse of the future through TrendsWatch, published by the American Alliance of Museums through its Center for the Future of Museums. This incisive and intriguing report predicts the factors that might impact museums in the future. The 2016 edition found five trends that all

museums—regardless of collection, size, or location—should ponder.

The Spectrum of Ability

Last year marked the 25th anniversary of the Americans with Disabilities Act. Since then museums have gone from fearing ADA as an unwelcome mandate to embracing it. Universal Design—creating spaces geared for all visitors, regardless of their physical abilities—is now the standard language of museum construction. Museum programming today considers people with disabilities as an equal constituency.

Advances in technology, though, are presenting a new consideration for museums. How do we accommodate people who use neurological interfaces, advanced prosthetics, even gene editing to enhance their experience? According to TrendsWatch, we have entered an era beyond just “assistive technology” (electric wheelchairs for instance). Now people are turning to “augmentive technologies” such as haptic vests and smart hairclips that translate sound into vibration for the deaf or hard of hearing. Or biometric implants and digital tattoos that allow people to use their proximity or gestures to heighten their visit, and bionic devices that turn ordinary people into superhumans.

Artist and “cyborg activist” Neil Harbisson is the apogee of this movement. He “hears” color through an antenna that he surgically implanted into his skull to translate light waves into vibrations. While it might be a bit of a science fiction fantasy to imagine future museum visitors experiencing art in a whole new way, the wearable tech trend is accelerating quickly and museums need to begin accommodating it now.

Virtual Reality & Augmented Reality

Ever heard of VR, AR, or IRL? These three acronyms are changing museums. VR, or virtual reality, is the suite of hardware and software that propels users into a digital fantasy world of amazing, immersive verisimilitude. AR, or augmented reality, provides a technological overlay onto the real world, enhancing experience with data, graphics, and other helpful content. IRL, of course, is “in real life”—the old-fashioned way—which is what VR and AR attempt to either escape or enhance.

Museum employees feel both excited and concerned about these technologies. The optimists see VR and AR as vehicles for users to interact digitally with museum content in a more immersive way. Pessimists fear AR and VR will become digital substitutes to IRL museum visits. However, this is sort of like the fear the baseball team owners expressed in the 1950s when they believed attendance would suffer if games were televised. Try getting tickets to a Red Sox versus Yankees contest now and see how that fear panned out.

Claude Monet, La Japonaise (Camille Monet in Japanese Costume), 1876, oil on canvas. 1951 Purchase Fund. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

The Struggle over Representation & Identity

Cultural sensitivities, today, have reached a boiling point. Icons of the past are being removed from the public eye because they commemorate a history of oppression: the Confederate flag, university edifices and programs named for controversial figures, team mascots representing racial stereotypes.

According to TrendsWatch, “museums, as public stewards of our collective history, find themselves enmeshed in the struggle over representation, identity, and material culture.” Museums have become forums for these important conversations about public monuments perpetuating oppression or serving as essential reminders of history’s mistakes. As institutions struggle over their iconography, museums, says TrendsWatch, “are called on to act as cultural HAZMAT teams.”

Out of this debate, arises the question of who, exactly, “represents” a culture and is authorized to speak for it. The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston confronted this head-on last summer with the controversy over “Kimono Wednesdays.” The museum encouraged visitors to don kimonos and pose for selfies with Monet’s La Japonaise. Protesters accused the MFA of insensitivity while defenders of the museum noted that the protesters were not of Japanese heritage, implying they did not have the moral authority to protest. Who was right?

Labor 3.0

With the advancements in technology, we all know that the nature of work has changed. One-quarter of all workers nationwide spend all or part of their days working from home, allowing the opportunity for a greater work/life balance.

This doesn’t seem to apply to low-wage workers, however, who are not typically offered flexible working arrangements. And technology seems arrayed against them too: over the next 20 years robots and artificial intelligence are projected to displace 47 percent of the American workforce, mostly blue-collar jobs.

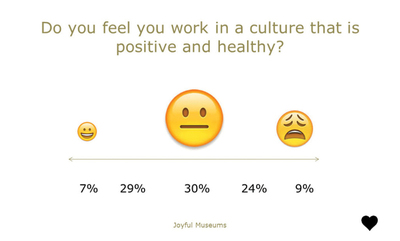

Museums are not immune to this trend. Despite the fact that museum jobs are highly competitive, a recent survey from the Joyful Museums Project found that only seven percent of museum professionals believe they work in a culture that is “positive and healthy.”

This general dissatisfaction has the potential to erode museum excellence from within, affecting everything from the visitor experience to donor relations. Museum employees have begun to call for better pay, more staff and board diversity, and more opportunities for advancement.

Museum leadership is starting to listen. My organization, the New England Museum Association, is facilitating and encouraging conversations on this topic at our upcoming 2016 conference and through our Career Growth Studio.

2014 Joyful Museums worker engagement study by Marieke Van Damme. Image courtesy of Joyful Museums.

Happiness

Calling a museum a business is like calling an eagle a bird. True, but much more than that. That’s why it’s a bit unsettling to see the museum field continuing to use business-related metrics such as profit and loss, ROI (return on investment), and economic impact as the primary weapons in its public advocacy arsenal. Sure, museums in varying degrees do benefit their communities with economic well-being, but their biggest impact on people is their ability to enhance education, quality of life, and overall happiness.

Fortunately, there are signs that bottom-line thinking is changing throughout society. Businesses are realizing that happy employees are productive employees—think of Zappos’ CEO Tony Hsieh’s “happiness movement” and book—and governments are beginning to supplant World War II-era measures of GDP/GNP with non-financial metrics that include happiness as indices. “Once we redefine success to include more than cash, museums are poised to make sizable contributions to our collective bottom line,” says TrendsWatch.

Dan Yaeger is the executive director of the New England Museum Association.