John Bisbee

John Bisbee’s studio—or forge or smithy, depending upon what’s happening there on any given day—is located on the back side of Fort Andross, a former textile mill in Brunswick, ME. Today its shed doors are swung open wide to a deserted parking lot with an unobstructed view of the mighty Androscoggin River.

John greets me and excitedly tells me about his brand-new “verb,” pointing to what was once a 12-inch spike. It’s been bent, pounded, and twisted into something akin to a pretzel and then flattened. Looking at it, and then to the wall where scores of them have been welded together, it’s hard to fathom the vision and industry that went into transforming this single unit into a large, ornate pattern reminiscent of graffiti or an Indonesian mandala.

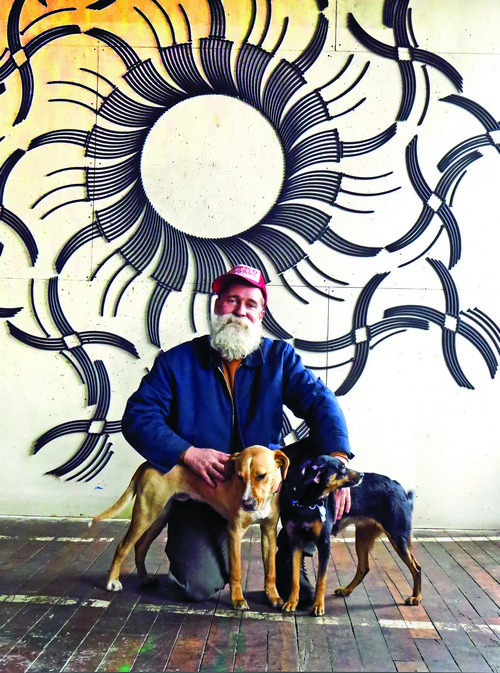

John Bisbee in his studio with his dogs, Chica and Wafer, in front of Cyclonaut #1. John Bisbee, Cyclonaut #1, 2014, heated, hammered and bent 12″ spikes, 11′ 9″ in diameter. Photo: David Wade.

I watch as he demonstrates how it was made, performing a well-rehearsed dance with a pair of attenuated tongs, pulling a glowing, cherry-red steel twelve-inch spike out of a small forge’s fiery mouth. He then drops the industrial-sized nail expertly into a custom-made jig anchored to a large steel-top table. There he mercilessly twists, pulls, and pounds it before dropping it onto the tabletop to be flattened, manipulated, and then dropped into a bucket to cool. The resulting oddly shaped squiggle (what John calls a “verb”) will be welded with countless others to form the baroque and masterful accretions that we now anticipate of him.

Bisbee’s 30-year obsession with the common nail began when he turned over a bucket of rusted nails while scavenging for found sculpture materials. The stuck-together nails continued to hold the shape of the pail, which caught his attention. He has been working exclusively with nails ever since, starting first with half-inch brads and increasing in size as his work has likewise evolved. He now works almost exclusively with the 12-inch “bright common” spike. There is limitless potential in this vernacular item—his job, he says, is to explore how far he can go to make something new every time.

Bisbee’s studio practice is a daily commitment, six or seven days per week. Over the last two years, he has had regular, reliable help in the form of “a team of handsome athletes”—all of whom are aspiring artists and were his students at Bowdoin College. John likens himself to a “pirate with a crew” and jokes that it’s “all asses and elbows, but it’s a blast working with these guys,” in part because he’d been working alone for the previous 29 years.

John Bisbee, Hearsay, 2013, bright common spikes, 7 x 6 x 5′, in front of Bisbee’s Floresco, 2012, bright common spikes, 12′ x 60′ x 18″. Photo courtesy the Shelburne Museum, Shelburne, VT.

Working solo all that time exacted a high price from a middle-aged Bisbee and he has gratefully come to rely upon a team to churn out his innumerable verbs. He’s acquiesced readily to their vitality, keeping him connected to an undiluted and unadulterated life force essential to the production of his work. Composed of many multiples of these individually formed “verbs,” Bisbee’s sculptures spring into life just as nature creates forms predetermined by the extraordinary purpose and inherent designs of DNA. Endless brainstorming, experimentation and problem solving are required to make art as innovative and superb, time after time, from something so ordinary as a nail.

John has come off quite a year, having shown recently in 5+5: New Perspectives at Storm King Art Center in Mountainville, NY; in Second Nature: Abstract Art from Maine at The Curator Gallery in New York City; and just last month with his New Blooms at the Shelburne Museum’s Pizzagalli Center, where he feels his work is the most evolved to date.

Suzette McAvoy, director of the Center for Maine Contemporary Art, has offered John Bisbee one of his first solo exhibitions when the center relocates to Rockland in 2015. Still, he doesn’t feel like he has any looming deadlines or the need to reach a particular destination. That’s good, because he prefers to be making art instead of looking for opportunity. John Bisbee’s experience thus far has been that opportunity has found him.

Andres Azucena Verzosa is an active proponent of New England arts and culture. He is co-editor of the forthcoming Art in Maine: Contemporary Perspectives (University of Maine Press, 2014).