Pissarro: Lifelong Anarchist

Camille Pissarro was “the only impressionist with a big police file,” notes Richard Brettell, the curator of Pissarro’s People, the big current show at the Clark Art Institute. The exhibition is focused not on the painter’s bucolic landscapes, but on the radical politics that informed them and, at times, got him into trouble with the authorities. He was a lifelong anarchist.

Camille Pissarro was “the only impressionist with a big police file,” notes Richard Brettell, the curator of Pissarro’s People, the big current show at the Clark Art Institute. The exhibition is focused not on the painter’s bucolic landscapes, but on the radical politics that informed them and, at times, got him into trouble with the authorities. He was a lifelong anarchist.

Of Sephardic Jewish ancestry, Pissarro was born in 1830 on the Caribbean island of Saint Thomas, then a Danish colony. His family was quite well-to-do, but in later years he never accepted anything from them except hand-me-downs. After moving to Paris, he married a servant in his mother’s household. He thought that art should be bartered or traded rather than sold, although he managed to make money from his. In 1889, he sent two nieces a suite of drawings called Turpitudes sociales, which included images of suicide, starvation, and corruption, intended to educate them on the evils of capitalism. (The Clark show marks the first public presentation of the album.) As far as impressionism goes, Pissarro was the quintessential outsider.

An early work, Two Women Chatting by the Sea (1856), depicts a pair of Afro-Caribbean women, one holding a basket, the other balancing a washing board on her head. While the hazy, tightly painted background is academic and little like the looser landscapes of Pissarro’s mature years, his attitude toward the figures does point toward his egalitarian credo. Both are nicely dressed and don’t seem particularly weighed down by their workloads. They have time to stop for a talk on a balmy day in a beautiful place. Brettell calls Pissarro’s provincial people “the peasants of the future.”

A decade or so later, Pissarro made a small but potentially inflammatory picture, Donkey Ride at La Roche-Guyon, which could be mistaken as merely charming unless you examine it in light of the artist’s politics. While a prosperous woman tends to her two well-dressed children, two poorly clad urchins look on.

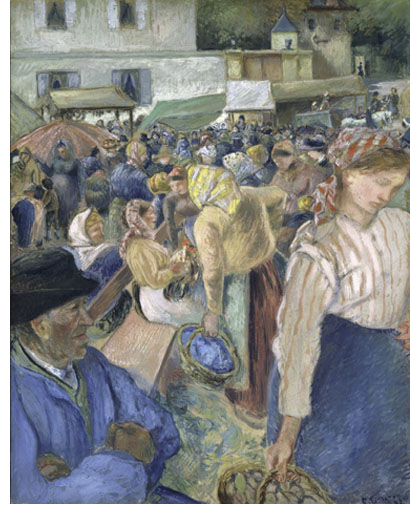

Brettell has framed this show so that theory is at least as interesting as the actual images, which are mostly not, after all, unfamiliar, especially in impressionist-rich New England. So when we look at the many scenes of rural life—harvesting, spinning, sowing, plowing, and shopping crowded country markets—we take his cue to think about politics. The workers depicted are absorbed in their tasks, generally bent over. Their posture is as telling as the quite different posture of Degas’ ballet girls.

Pissarro paints his workers as dignified rather than downtrodden. They blend into their pastoral settings; the artist uses the same free brushwork and lyrical palette, dominated by quiet greens, blues, russets, and golds, to depict fields and farmers. In Apple-Picking (1886), the women doing the job are engulfed in the serene, idyllic setting, with leaves overtaking the one in front. Here indeed are the contented “peasants of the future.” The pickers are stationary figures; their poses might indicate activity, but they seem timeless, like the strolling figures in Seurat’s contemporaneous A Sunday on La Grande Jatte.

Pissarro’s workers are iconic types rather than individuals. Where the show reveals individual personalities is in the many portraits of his family. He drew and painted and made prints of his children reading or making art themselves, not only because these activities encouraged them to sit still to pose, but because it was evidence that he encouraged them to pursue activities he felt were useful. Jeanne Pissarro, Called Cocotte, Reading, sets a daughter in a richly detailed room, with red-figured upholstery on a chair, a tapestry thrown over the sofa where Cocotte sits, and, behind her, her father’s own paintings in very sketchy style, as if to say, I’ve already painted them.

Pissarro’s workers are iconic types rather than individuals. Where the show reveals individual personalities is in the many portraits of his family. He drew and painted and made prints of his children reading or making art themselves, not only because these activities encouraged them to sit still to pose, but because it was evidence that he encouraged them to pursue activities he felt were useful. Jeanne Pissarro, Called Cocotte, Reading, sets a daughter in a richly detailed room, with red-figured upholstery on a chair, a tapestry thrown over the sofa where Cocotte sits, and, behind her, her father’s own paintings in very sketchy style, as if to say, I’ve already painted them.

The Cocotte picture is matter-of-fact. Those of her sister, Minette, Pissarro’s favorite child, are not. Minette died at age eight. A heartbreaking progression of images records her brief life. Pissarro shows her as a tiny child, standing in a nicely furnished room, then seated in a lush garden, then shut inside a darkened room, slumped over, holding a fan but not using it. Her hair has been cut very short. Finally, there is a lithograph from 1874 that shows her on her deathbed, in profile, sunk against the pillows and sheets and almost overwhelmed by them. How touching that these works, like Turpitudes sociales, were intended only for the artist’s family, not for public consumption.

In the anti-Semitic riots in France following the Dreyfus affair, Pissarro, who had a distinctly Jewish visage, was trapped in his Paris hotel rooms with little to paint except himself and the view outside. Hence he creates a series of particularly poignant late self-portraits, including one showing him clad in somber black, holding his palette, looking out at the viewer as if questioning what his cherished beliefs had come to. Taken with the expectations depicted in his earlier work, the picture might urge some of us, more than a century later, to look at our own beliefs and their effect—or lack thereof—on our own world.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________

Christine Temin was the art and dance critic at the Boston Globe for over two decades and now writes for a variety of international publications. She has taught at Middlebury College, Wellesley College, and Harvard University. Her most recent book is Behind the Scenes at Boston Ballet, published by the University Press of Florida.