Playing with Older Forms

Composer and harpist Hannah Lash in her office at Yale School of Music. Photo: Susan Rand Brown.

A burst of color on a gray day, the composer and harpist Hannah Lash, who joined the faculty of Yale University’s School of Music when barely out of her twenties, hurries up Chapel Street during a sudden chilly rain, high boots and cherry red coat signifying style and energy. “Oops, forgot the umbrella,” she laughs. Once inside the music department’s brick and brownstone building, Lash smiles in the direction of a few students, instrument cases slung over their shoulders, and speeds up a flight of stairs. The nameplate by her office door reads simply, “Hannah Lash: Composition Studio.”

Within this intimate studio, Lash’s world is defined by an ash wood harp embellished with floral swirls, and behind that, a mahogany piano, J. S. Bach’s Baroque masterpiece The Well-Tempered Clavier on its stand. She is one of New England’s most sought-after contemporary voices, whose compositions, solo through symphonic, are grounded in the traditions of European classical music while commissioned and performed by cutting-edge ensembles. Sources of inspiration include German Romantics Robert Schumann and Franz Schubert, as well as contemporary composer Martin Bresnick, one of her most important teachers and now her colleague. Within Yale’s Gothic campus, the prize-winning composer—whose honors include an ASCAP Morton Gould Young Composer Award and a Charles Ives Scholarship from the American Academy of Arts and Letters—is very much at home.

Lash’s calendar is packed. The accomplished harpist with a Harvard University PhD in Composition and an Artist Diploma from Yale is busy familiarizing budding composers with the principles that underlie her own work. Now completing a second harp concerto and a nontraditional choral requiem, her world premieres are creating a buzz, from Yale’s Sprague Hall to the Chicago Art Institute, New York City’s Carnegie Hall and intimate venues like Lower Manhattan’s Le Poisson Rouge. She receives national and international invitations to music festivals, where she meets other adventurous composers and musicians.

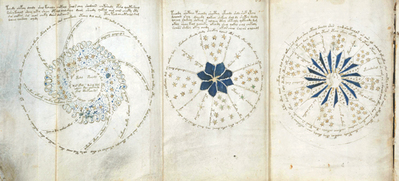

The Voynich Manuscript, page 124, parchment with folio folding leaves. Courtesy of the Yale University Library catalog.

Leaning forward, the home-schooled daughter of two librarians speaks engagingly of her process as a composer and her upcoming concerts, and of becoming, at the modest age of 34, the youngest faculty member in an inspiring, supportive music community she describes as “a dream come true.”

The much-anticipated second movement of her Voynich Symphony, commissioned by the New Haven Symphony Orchestra (she is composer-in-residence) will premiere May 19 in New Haven’s Woolsey Hall. A day later, Beowulf, Lash’s chamber opera commissioned by the Guerilla Opera, will premiere at the Boston Conservatory. Passionate about vocal music, she teaches both 16th and 18th-century counterpoint, whose polyphony she connects to her own musical ideas. Lash wrote the Beowulf libretto as well as scoring the piece.

Lash’s symphonic inspiration lies more in the idea of the Voynich, an undeciphered 15th-century manuscript filled with looping script and obscure botanical images kept under wraps in Yale’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, than in interpretations of the document itself. Her fascination with its odd beauty deepened when she got to turn a few of its 240 fragile vellum pages. “I’ve always been intrigued by The Voynich. I find it beautiful and strange. Its inscrutability, the unknowing and the beauty for beauty’s sake, intrigued me more than any attempt to understand what it was saying,” Lash comments.

The NHSO residency provided Lash with an opportunity to compose a four-part symphonic piece loosely based on this manuscript. Typically, she said, a contemporary composer and particularly a young composer might be commissioned to write a ten or 12-minute opening. “It’s hard to commit to a piece of this length,” she says in a voice both amused and understanding. “This meant I could write an extended piece for orchestra, something that had interested me for awhile.” The third movement will be performed this fall, and the completed symphony in 2017.

As it takes shape, Lash’s Voynich Symphony is only abstractly related to the manuscript. Herbal, the opening movement, performed this past October, was loosely about botanical life, “the organic outgrowth of ideas, the way things stem from each other,” she says. Astronomical, the second movement, promises to be celestial in feeling, inspired by the slow orbiting of astronomical bodies: “Astronomical has a slower tempo, and deals with a vastness, a darkness that unfolds.” Biological will be a more lighthearted scherzo movement, and the fourth and concluding movement, Cosmological, circles back to themes threaded throughout.

Hannah Lash in rehearsal with students at Yale University.

“I sit very quietly when I compose. It’s important for me to let my inner ear get as much free reign as it needs—to let my imagination run wild,” Lash says. Asked if she commits music to paper during the composing process, she pauses, as if searching for the precise note. “Yes, I do, but I have to think for a long time so I can get an aural picture of the piece in my imagination. Then I can begin to sketch on paper.” Do composers typically complete a composition before writing it down? Lash’s response suggests the confidence generating her big-picture musical ideas: “I think we all do it a little differently, but first getting a good sense of the muscularity of the music was an important skill for me to develop.

“I like to call mine ‘contemporary music’ because it simply means music being written now, and doesn’t limit the idea to ‘post-Minimalist,’ let’s say, or ‘neo-Tonalist’ or ‘neo-Expressionist,’” she says, with the passion of someone describing herself for the first time. “I don’t feel comfortable with those labels. The music I write is an incredibly personal thing, and if I were to label it, it would feel much less personal than writing simply what I have to.”

Imagine a listening experience reflecting the Romantic expressiveness of Robert Schumann and the ethereal harmonies of contemporary Estonian choral composer Arvo Part. Lash’s elegant textures reference this rich heritage while continuing to stretch the contemporary repertoire. For those unfamiliar with sonic cosmologies light years from what Grammy Awards offer, relaxing into timbres transcending labels can be like tuning into a fresh, uniquely satisfying wavelength. The vistas Hannah Lash commands are that expansive.

Susan Rand Brown is a poet, art critic and frequent contributor to Art New England. She also writes for Provincetown Arts, The Provincetown Banner, and Inspicio, and teaches literature in Hartford, CT.