View from the Outpost

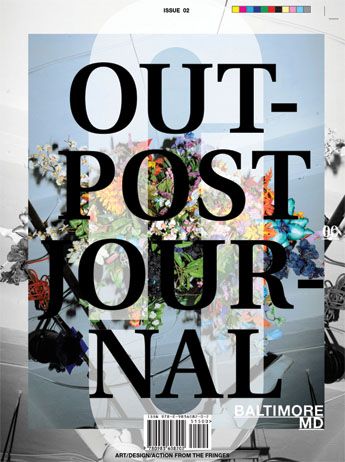

This column derives from my interview with Providence-based Manya K. Rubinstein, publisher and co-editor of the nonprofit Outpost Journal, having a “focus on how art and design are changing our urban landscapes, one city at a time.” We met at the Box Office, where another of her ventures, Bandit Communications, has space in a recycled shipping container office building that is “green” and houses a dozen startup office and studio spaces. Manya held the proof for the second volume of her extraordinary journal, dedicated to the city of Baltimore, whose printing is partially funded by a successful Kickstarter campaign.

Rubinstein’s project is a perfect example of the new regionalism theme of this issue of Art New England. In our conversation, she nearly breathlessly explained, “What’s out there? Actually there’s a lot going on if you just take some time to actually get engaged with a community, meet people, see what is happening. An interesting insider/outsider perspective occurs. So for our journal, the past two [initial] issues, we explored this with a core team mostly from Providence and New York, though we had met many of the team via Providence connections. We also recruited local folks from each city as writers and guides to help us explore what makes their place really interesting and special because I don’t think you get the full perspective exclusively as an insider or outsider, I think you must combine the two.”

Rubinstein’s energetic, inclusive mission relates to the concept of creative placemaking recently championed by the NEA. While its goal is to conjoin various constituents to economically advance urban regions around art and cultural activities, her ethos is instead based in artistic and creative living. She asks how place informs artistic community and how an artistic community informs place. The notion of what she calls “intentional” arts communities or “arts ecologies” is fundamental to exploring cities akin to Providence.

Each city examined contains its own quirkiness and distinctive, edgy practices; accordingly, the journal recognizes uniqueness as well as the character of artistic output. Focusing first on Pittsburgh, Rubinstein has begun identifying and profiling other small, fringe cities—termed outposts—whose art scenes are interpreted through a seventy-page journal of bold graphic design, photography, cogent articles of various lengths, arts calendars, and original art insertions as well. The journals combine aesthetic and intellectual experience in a limited- edition product carefully attuned to each region. Up front about never pretending to be exhaustive in exploring creative lives, Rubinstein nonetheless harnesses her own elaborate network to pry loose and push far beneath the surface of a city’s communities. She is modest. Concentrating on outliers, twenty to forty years old, she propels consideration of communities’ wide-ranging dimensions. The focus is neither traditional nor institutional.

The new regionalism encompasses the move toward recognizing the values of local art practice and its inspired initiatives. These started with the food movement, Rubinstein recalls, and lately have moved into clothing, supporting producers and stressing principles of selectively “buying into.” In lieu of the conventional competitive artistic practice of selling in the large commercial marketplace, Rubinstein and her colleagues try to “loop back in” to the local, and give a voice to talented artists, both well-known and not yet broadly recognized, but all sharing an intentional creative community. The project is not utopian; instead, a dystopian aspect may prevail, Rubinstein admits, at a time when so much feels beyond one’s control politically. In contrast, effecting change in a community can happen fluidly, immediately, by participating in its urban arts.

Rubinstein sees Outpost Journal as an authentic means to activate exchange between various art communities. She envisions “sparks to be made” for example, in curating an exhibition of works by artists featured across issues, with New York artists having connections to those same communities, bringing people together and mixing it up, encouraging meetings of change-makers in those cities. With additional comparative issues, after some ten to fifteen are released, an “idea bank” will have been developed for informing new projects.

When a Providence issue eventually is devised, different ways will have been investigated to involve guest curators and integrate multiple art communities. Rubinstein was a comparative literature major at Brown. The outlier who is Rubinstein actively retains the sense of the comparative from her strategic, magnetic place on the national art scene.

_____________________________________________________________________________________

Judith Tolnick Champa is the editor-in-chief of Art New England.