Welcome to Picasso’s Studio

Installation shot of the exhibition Staring Back: The Creation and Legacy of Picasso’s Demoiselles d’Avignon, utilizing technological tools such as iPads. Courtesy of Fleming Museum of Art, University of Vermont, Burlington, VT.

How do you create an exhibit around a painting that can’t be borrowed? That was the conundrum facing Janie Cohen, director of the Fleming Museum of Art in Burlington, VT, and an established Picasso scholar. The painting, Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907), has hung in New York’s Museum of Modern Art since 1939 and has been loaned just once, for a 1988 exhibit in Paris and Barcelona. “The value is just too enormous,” Cohen explains of the work that triggered cubism and changed the course of modern art.

Yet the painting’s absence is hardly a loss in the Fleming’s exhibit, called Staring Back: The Creation and Legacy of Picasso’s Demoiselles d’Avignon, on view in the East Gallery until June 21. With the help of an unusually broad range of technological solutions—at least for an art museum—the exhibit creates an immersion experience for visitors.

A looped soundscape of turn-of-the-century Montmartre street sounds draws visitors instantly into the era. They “enter” Picasso’s 1908 studio, the interior of which appears as a 2008 painting by Damien Elwes, projected to fill one large wall and rendered three-dimensional with a digitally added light source that moves past the studio objects on a loop, creating shadows. Demoiselles appears in digital projection on a canvas the same size as the actual painting, leaned casually against the wall beside the projected studio as if Picasso just completed it.

A looped recording of historical comments makes it clear what Picasso’s contemporaries thought of the work at the time. “Painting of this sort was an impasse at the end of which lay only suicide,” reads a voice representing André Derain, his is only one of a dozen shocked reactions. The hypersonic sound installation—highly focused so it’s only heard while standing on a marked spot—fades out in a jazzy repetition of Georges Braque’s reaction: “[It’s] like drinking kerosene in order to spit fire.”

Installation shot of the exhibition Staring Back: The Creation and Legacy of Picasso’s Demoiselles d’Avignon, utilizing technological tools such as Leap Controllers. Courtesy of Fleming Museum of Art, University of Vermont, Burlington, VT.

Opposite the “studio” are rows of iPads and Kindles on which visitors can swipe through every one of Picasso’s 700-plus studies and sketches for this painting. The actual sketches are in the Picasso Museum in Paris and can otherwise only be viewed together in a two-volume catalog published for a 1988 exhibit.

Staring Back also contains a more didactic digital display on two walls that provides images and summaries of each of Picasso’s numerous sources and inspirations. These include not just the expected nudes by Titian and Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, but Cohen’s own recent contribution to the field: colonial “anthropometric” photographs, dating from the 1880s and on, of African-American women who are posed nude in standing and sitting positions, often in groups of five. Such photos were widely circulated in France as erotica under the guise of ethnography, and, Cohen contends, they were as influential in the creation of Demoiselles as Picasso’s exposure to African masks and sculpture at the Trocadéro.

This art history section of the exhibit advances automatically from source to source, though visitors can pause it using hovering hand motions over two Leap Controllers. Reams of information are made accessible within this relatively small space.

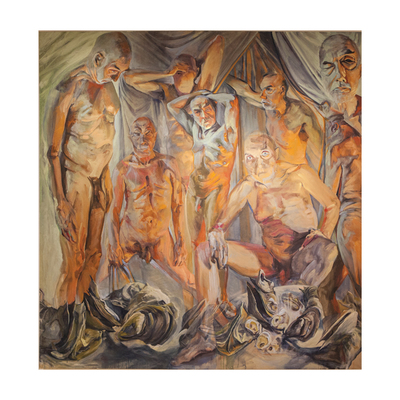

Two final rooms contain Demoiselles’ “legacy”: the widely variant responses of other artists to Picasso’s seminal work since it was publicly unveiled in 1916—almost a century ago. Many of these works confront viewers with an aggression equal to that of their inspiration, such as Gerri Davis’s painting Bordel (2010), which places an elderly male nude, representing Picasso, in the demoiselles’ standing and crouching positions.

Gerri Davis, Bordel, 2010, oil on linen. Courtesy of the artist.

Jenn Karson and Coberlin Brownell, two Burlington-area tech gurus with backgrounds in art, engineered the technology for Staring Back. Karson focused on sound art while earning her MFA in design and technology at the San Francisco Art Institute; she now teaches in the University of Vermont’s engineering college. For the street soundscape, she researched turn-of-the-century Parisian guidebooks, among numerous sources, then layered sounds of cathedral bells, a passing horse and cart, a cooing dove, the clink of tableware, bits of French conversation and other clips. The whole is broadcast from behind a wall-mounted 1907 Edison phonograph horn, which Karson found for the exhibit.

Beside the horn, the tech gurus created a video installation. Brownell focused on augmented reality while earning his MFA in emergent media at Champlain College in Burlington, where he now teaches. The video begins with the iconic photo of a 23-year-old Picasso standing in the square outside the dilapidated Bateau-Lavoir, which housed his studio. Slowly, the image fades to a black-and-white video collage of Karson’s engineering student impersonating Picasso against the same background, smiling knowingly.

Like the hypersonic sound installation in the next room—where the comments are read not by actors but by locally known curators, artists and other community members—the video component is intended to “make the piece really active for the campus and broader community,” says Karson. At the same time, the team wanted the immersion experience to “avoid nostalgia.” Karson adds, “The dissonance of

having that student there…it’s so true. We’re bringing ourselves to that other time period, but we’re not there.”

Staring Back, however, brings visitors pretty close. As Cohen points out, Demoiselles itself continues to confront contemporary viewers with undiminished power. “It’s such a cultural monolith—and it’s still disturbing. You’re attracted to it but you’re partly repelled, too.”

Amy Lilly writes on the arts and humanities for Seven Days, Vermont’s alternative newspaper, and for Vermont Woman, where she is also associate editor.