Wolf Kahn

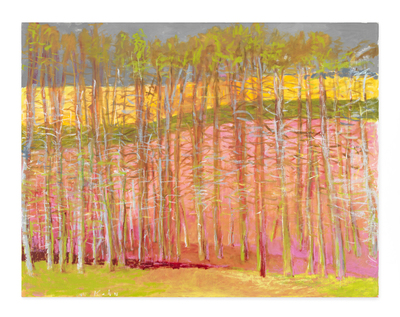

Wolf Kahn, Trees Against Magenta, 2014, oil on canvas, 40 x 52″.

“Enthusiasm, you know, means to be inspired by the gods.” At nearly 88, eminent American painter Wolf Kahn’s blue eyes smolder with impish vitality. “The most important thing for a painter is the capacity to feel and express enthusiasm.”

The Vermont house and studio where Wolf Kahn has lived and worked each summer since 1968 is a study in painterly persistence as well as a coincidence of opposites. Early twentieth-century farm tools, that still see use, share the space with trays of pastels, bottles of paint thinner and “El Pico” coffee cans blooming with brushes. Kahn still spends four months of the year painting the landscape of West Brattleboro. And despite the apparent uniformity of his instantly recognizable work, he continues to open new territories to mine within it.

“Always gnawing on the same bone allows me to have a coherent development,” he told me on a recent visit. “Of course, you know, only after 70 years does that appear.”

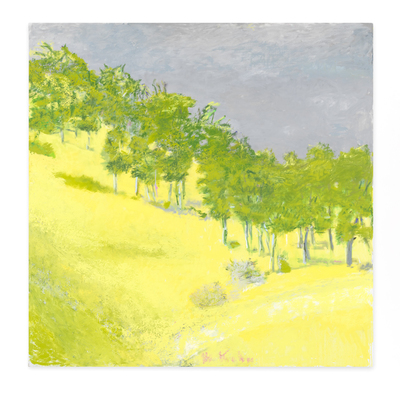

Kahn is producing the most energetically confident paintings of his long career. “I’m interested in an overriding rhythm,” he says. “I’m trying to get beyond intention. As soon as you have a brush in your hand you have a tool that’s going to make you descriptive. I didn’t want to be a descriptive artist.” His work synthesizes his early training with New York abstract expressionist giant Hans Hofmann (Kahn was his studio assistant), the palettes of Matisse and Bonnard, the sweeping bands of color of Rothko and the color-field painters and the atmospheric qualities of American impressionism.

Used to spending 10 hours in the studio at a stretch, Kahn still works every day. He has five shows booked for this year alone, including four in the United States, at Ameringer|McEnery|Yohe in New York; Addison/Ripley Fine Art in Washington, DC; Marianne Friedland in Naples, FL; and Jerald Melberg Gallery in Charlotte, NC; and Kunsthaus Buhler in Germany.

Financial success doesn’t seem very important to Kahn (he describes himself as a “working man”). One suspects Kahn isn’t all that interested in the region per se either, unless as an excuse to use the Fauve-like chromas of autumn year-round. “People think that I’m painting Vermont,” he said, “but I keep saying I’m painting paintings.”

A pastel worktable in Kahn’s Vermont studio. Photo: Christopher Volpe.

That Kahn’s work is “pleasing” (he’s likely the most popular colorist in America) belies its unsentimental formalism. In fact, his fields of blazing color are deeply nuanced and almost as a rule moderated by subtle countering complexities applied in complements, neutrals and composite grays. As his friend Louis Finkelstein described it, abstract “vectors and color tensions” in Kahn’s paintings “elicit alternative readings.”

Recently Kahn, who has long resisted non-representational painting, has been allowing himself a bit of the influence of Jackson Pollock’s process, “in that he didn’t want to know what his painting would look like when it was done.” In other words, chance and spontaneity are playing ever-larger roles. Additionally, Kahn’s paintings are spending longer periods of time on the easel. “What really interests me now is creating textures,” he said, which requires multiple applications of layered paint. “I’m still painting landscapes, but I find the more stuff I put on, the better the painting.”

For Kahn the process is intuitive and largely unconscious; he’s a colorist who doesn’t theorize about color. “I never think about color,” he said. “Color came as a byproduct of other concerns.” Yet he is undeniably a master of controlling it, carrying phthalo blues, acid greens, and strident yellows to “the danger point” and back and choosing “colors that everyone hates” for the sake of treating “ingratiating elements in an

austere way.”

He mixes his colors directly on the canvas, treating the palette as a “supply warehouse” for untubed paint. His palette has brightened consistently over time, and he enjoys using contemporary hues previously unavailable to painting. Kahn mixes color optically, yet unlike the American impressionists who also used broken color, it isn’t so much to imitate light as to create degrees of airiness and solidity that move the eye forward or back in his paintings, recalling Hans Hofmann’s “push and pull.”

As ever, Kahn considers himself a formalist, building “recognizable structures that arrive at their meaning easily.” Yet the spontaneity that feeds his “enthusiasm” trumps any structural planning. “I try to let things happen,” he said. “I like painting that ends up a surprise. I want to always be trying things I haven’t done before and that I haven’t seen other people do and that allow me to be surprised. I’ve never had any kind of program.”

Wolf Kahn, Uphill, 2014, oil on canvas, 52 x 52″.

Indeed, he says his paintings often begin with a series of “mistakes” that “besmirch” the too-perfect canvas. Ragged bands of opposing colors spread rapidly across the space and soon new spatial and formal relationships emerge as additional color layers accrue. By the end, the canvas is a charged field of subtly modulated relationships. Calligraphic marks, executed with oil sticks and often quite dense, may ultimately score the intensely variegated fields and “vectors” of color.

Within the work and without, seeming contradictions abound. Kahn is actually a New Yorker and paints the other eight months of the year in his 4,500-square-foot loft studio in Chelsea. Although the New England landscape remains a constant, the two geographies correspond to the disparate forces at work beneath his brush. For decades he has been a highly visible force in the movement to combine the freedom and immediacy of abstract expressionism with recognizable subject matter.

Kahn is an extraordinarily literate artist; he’s currently memorizing Wordsworth’s sonnet beginning, “The world is too much with us, late and soon.” Toward our interview’s end he good-naturedly searches for the exact wording of a quote that may or may not be by Samuel Johnson. It’s one that neither I nor his assistant can track down on Google, something to do with holding two contradictory ideas in the mind at once. Later, the closest I can come is Kierkegaard, who wrote in favor of a faith not unlike his own, one “that persists in the face of the impossible” because “humans have the capacity to simultaneously believe in two contradictory things.”

Christopher Volpe is a New Hampshire-based artist and teacher who has taught art history at the New Hampshire Institute of Art, Chester College of New England and Franklin Pierce University.