Abject Expressionism

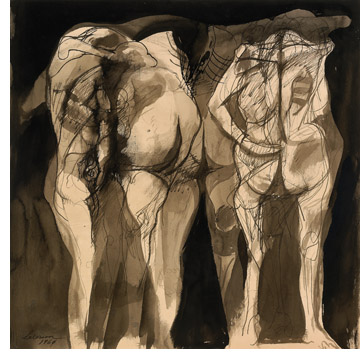

Painter Rico lebrun’s haunted, expressionist scenes of crucifixions, insect-like Magdalenes and Nazi death camps made him one of the most prominent artists of the Los Angeles scene in the years immediately following World War II. “Composition was born out of the shocked heart,” he wrote in 1959. “I had to find out for myself that pain has a geometry of its own; and that my being…wanted to speak out in a single shout.”

Painter Rico lebrun’s haunted, expressionist scenes of crucifixions, insect-like Magdalenes and Nazi death camps made him one of the most prominent artists of the Los Angeles scene in the years immediately following World War II. “Composition was born out of the shocked heart,” he wrote in 1959. “I had to find out for myself that pain has a geometry of its own; and that my being…wanted to speak out in a single shout.”

While artists in New York looked to Paris and built on Picasso’s cubist experimentation, many artists like Lebrun in the American “provinces” drew inspiration not just from Picasso’s formal invention, but also from the artist’s political broadsides like Guernica. “Cognizant of the atrocities of the recently ended world war, the L.A. Raw artists of the 1940s and 50s emphasized a dark, reductive vision of humanity, a kind of ’Abject Expressionism,’” curator Michael Duncan writes in the catalogue for L.A. Raw: Abject Expressionism in Los Angeles 1945–1980, From Rico Lebrun to Paul McCarthy at the Pasadena Museum of California Art through May 2012.

The exhibition’s significant contributions are to tease out links between Lebrun and the present, as well as to illuminate another regional perspective in the often-untold history of the past century of American art outside of New York. In fact, this “Abject Expressionist” strain in American art, to use Duncan’s brilliant coinage, had already appeared among Boston artists like Hyman Bloom and Jack Levine in the 1930s and 40s, inspired by the German Expressionist art of World War I and the artists’ own impoverished upbringings as immigrants or the children of immigrants fleeing wars and ethnic violence in Eastern Europe. Many artists of this first generation faced life-threatening experiences. Bloom’s hometown in Latvia sat between warring Germans and Russians; Lebrun was an Italian immigrant who had served in World War I and then watched from the United States as fascism and World War II engulfed his homeland.

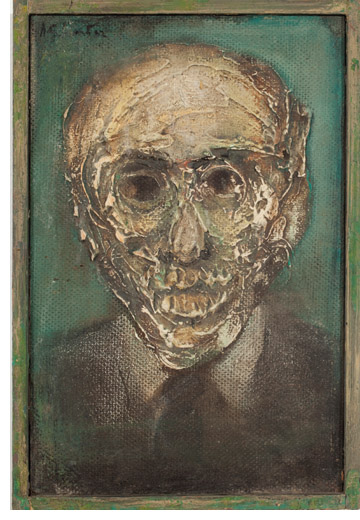

Elsewhere, in Chicago in the 1920s, Ivan Albright returned from making medical drawings in a French hospital during World War I to begin painting people so world weary that their flesh seems to rot before our eyes. After World War II, Chicago “Monster Roster” artists like Leon Golub (a WWII veteran who said he decided to become an artist after seeing Guernica), Nancy Spero, and H.C. Westermann (a vet of WWII and Korea) turned the style more folksy, visionary, and abstract. “While abstract expressionism rules the cash register in Manhattan’s prospering art galleries, young artists across the land are turning back to images—but with a difference,” TIME magazine reported in 1959. “Their figures are human, but horrible. The horror school has its center in Chicago.”

Bloom, Levine and Lebrun were linked in the Museum of Modern Art’s Americans 1942. The eighteen artists mainly blended social realism with eerie surrealism. Painter Bernard Chaet has said Willem de Kooning told him that when de Kooning and Jackson Pollock discovered Bloom’s fiery kinetic paintings of chandeliers and Christmas trees in this show, they thought him the first abstract expressionist. But by 1946, critic Clement Greenberg was arguing in The Nation, “I do not think that Bloom’s expressionism offers great possibilities for the future.” The following year, Pollock poured his first drip paintings.

Bloom, Levine and Lebrun were linked in the Museum of Modern Art’s Americans 1942. The eighteen artists mainly blended social realism with eerie surrealism. Painter Bernard Chaet has said Willem de Kooning told him that when de Kooning and Jackson Pollock discovered Bloom’s fiery kinetic paintings of chandeliers and Christmas trees in this show, they thought him the first abstract expressionist. But by 1946, critic Clement Greenberg was arguing in The Nation, “I do not think that Bloom’s expressionism offers great possibilities for the future.” The following year, Pollock poured his first drip paintings.

The Bostonians disappeared from the picture when curator Peter Selz, who fled Nazi Germany in the 1930s and has spent his career focusing on German expressionism and abject expressionist artists (he contributes to the L.A. Raw catalogue), linked Lebrun, Golub, and Westermann with Pollock, de Kooning, Francis Bacon, Jean Dubuffet, and Alberto Giacometti in the 1959 MoMA exhibition, New Images of Man. New Yorker critic Robert Coates reflected the Big Apple’s verdict by calling the show “so capricious and so far from representing any broad, true impression of the atmosphere of today that it is hardly worthwhile going into any critical appraisal of it.”

Despite the similarities between the raw art of Boston, Chicago, and California, and curators drawing occasional connections, the artists mainly worked in ignorance of each other. And the tendency to compare all developments in American art with New York rather than looking elsewhere continues to obscure these connections. As the artists were developing their styles, they could see what was going on in New York or the European art capitals via the New York and European art press and some traveling exhibitions, but these rarely allowed for lateral views to developments that would make clear the similar thinking in Boston, Chicago, San Francisco, and Los Angeles. One of the striking things about the launch of the lowbrow art bible Juxtapoz magazine in 1994 is that it made clear how widespread this gothic expressionist style persists, and fostered it by displaying together its geographically diverse examples. Across the country, artists pioneered nearly the same abject expressionist response to the formalist, modernist mainline, spreading like a repeated, isolated mutation along an archipelago.

The triumph of Pollock and his action painter comrades wasn’t simply some merit system in which the best stuff happened to be abstract and from New York. From the 1930s to ‘60s, the CIA, the US State Department, and the US Infor-mation Agency—with help from MoMA and major American corporations—organized exhibitions of new American art in Europe and Latin America to bear witness to the benefits of American-style democracy, capitalism, and freedom. These shows promoted New York abstract expressionism abroad and were key to the style’s conquest of the art world. But when Levine, by then a World War II veteran living in New York, exhibited his 1946 painting satirizing fat-cat generals celebrating after the end of the war in a State Department exhibition in Moscow in 1959, the House Un-American Activities Committee accused him of communist affiliations and called him to Washington for questioning. Is it any surprise that the art that rose to the top abandoned direct references to its troubled times?

The triumph of Pollock and his action painter comrades wasn’t simply some merit system in which the best stuff happened to be abstract and from New York. From the 1930s to ‘60s, the CIA, the US State Department, and the US Infor-mation Agency—with help from MoMA and major American corporations—organized exhibitions of new American art in Europe and Latin America to bear witness to the benefits of American-style democracy, capitalism, and freedom. These shows promoted New York abstract expressionism abroad and were key to the style’s conquest of the art world. But when Levine, by then a World War II veteran living in New York, exhibited his 1946 painting satirizing fat-cat generals celebrating after the end of the war in a State Department exhibition in Moscow in 1959, the House Un-American Activities Committee accused him of communist affiliations and called him to Washington for questioning. Is it any surprise that the art that rose to the top abandoned direct references to its troubled times?

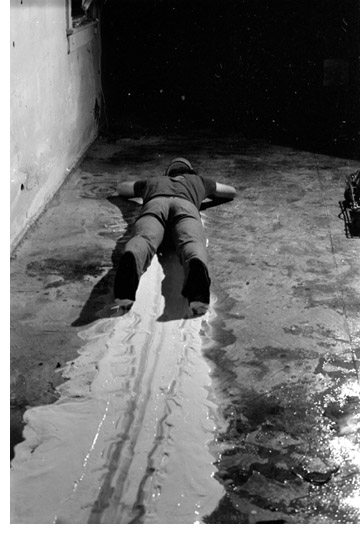

In California, abject expressionism mutated into junk assemblages like Bruce Conner’s 1959 sculpture Child, which resembles a desiccated baby bound to a highchair, and Edward Kienholz’s Five Car Stud (1969–1972), an immersive, life-sized installation in which white men have surrounded their African American victim with their cars to torture him to death. Repress-ion of such socially engaged art continued as L.A. authorities accused Kienholz, Wallace Berman and Connor Everts each of making public obscenities.

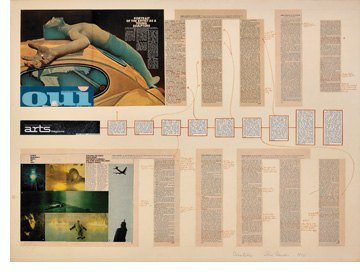

L.A. Raw draws in African-American artists like Betye Saar, John Outterbridge, and David Hammons who often appear to be outliers amidst mainline modernism’s formalism but adopted an abject expressionist realism in the ‘60s because they needed to address the tortured reality of racial oppression in America. All of this art shares a dark, distressed look, but many histories lose the Abject Expressionist strain when it changes guise and splits into two streams in the ‘60s. On the one hand, it turned pop in the inflammatory Vietnam cartoons Peter Saul made in California and the stumblebum Richard Nixon and Klansman paintings of Philip Guston, who split his time between upstate New York and Boston. But as this pop Abject Expressionism blossomed among Chicago’s Hairy Who gang (Jim Nutt, Gladys Nilsson, Karl Wirsum, Ed Paschke, Roger Brown, and Christina Ramberg) as well as Robert Williams, Gary Panter and today’s Lowbrow artists (Mark Ryden, Tim Biskup, Camille Rose Garcia, Barry McGee, and Gary Baseman) it often lost its social critique. An exception is Providence artist Brian Chippendale’s psychedelic underworld screenprints of the past decade criticizing Providence real-estate development, American consumerism and the War on Terror.

L.A. Raw draws in African-American artists like Betye Saar, John Outterbridge, and David Hammons who often appear to be outliers amidst mainline modernism’s formalism but adopted an abject expressionist realism in the ‘60s because they needed to address the tortured reality of racial oppression in America. All of this art shares a dark, distressed look, but many histories lose the Abject Expressionist strain when it changes guise and splits into two streams in the ‘60s. On the one hand, it turned pop in the inflammatory Vietnam cartoons Peter Saul made in California and the stumblebum Richard Nixon and Klansman paintings of Philip Guston, who split his time between upstate New York and Boston. But as this pop Abject Expressionism blossomed among Chicago’s Hairy Who gang (Jim Nutt, Gladys Nilsson, Karl Wirsum, Ed Paschke, Roger Brown, and Christina Ramberg) as well as Robert Williams, Gary Panter and today’s Lowbrow artists (Mark Ryden, Tim Biskup, Camille Rose Garcia, Barry McGee, and Gary Baseman) it often lost its social critique. An exception is Providence artist Brian Chippendale’s psychedelic underworld screenprints of the past decade criticizing Providence real-estate development, American consumerism and the War on Terror.

L.A. Raw overlooks this body of work, but Duncan draws connections with Chris Burden and Paul McCarthy’s violent, seemingly self-endangering performances as well as Judy Chicago’s feminist 1971 lithograph Love Story, depicting a photograph of a hand holding a gun to a woman’s crotch above sadomasochistic text from The Story of O. McCarthy, Burden, and Chicago’s art might not mirror the fractured, tortured expressionist painters that came before, but a similar current of humanist concern crackles through their work. The pogroms, world wars, and death camps that haunted abject expressionists in the first half of the century have been supplanted by concerns about Vietnam, feminism, and civil rights. Still, it’s not hard to see resemblances between Lebrun’s crucifixions and Burden having himself crucified atop a Volkswagen. At the time, Burden’s social concern was obscured by the violent sensationalism of, say, having himself shot in the arm with a rifle, but in light of his later work that directly addressed Cold War nuclear arsenals, his explorations of American violence from Vietnam to the Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr. assassinations are striking.

“For many this dark, quirky art seemed to have emerged out of the blue,” Duncan writes, but the art of Lebrun and aesthetic kin in L.A. “set the tone for ensuing generations of figuration, encompassing political, ethnicity based, feminist, and body oriented art.”

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

Greg Cook is the custodian of The New England Journal of Aesthetic Research and a critic for The Boston Phoenix and The Providence Phoenix.