Aesthetics of Disaster

Resa Blatman, The Water Project / Rising Tide 3 (detail), 2016, oil and latex paint on hand-cut Mylar, 96 x 300 x 10″. Commission for the Somerville Hospital Atrium, Somerville, MA.

The 2015 Paris Agreement was at once a moment of triumph and despair. For the first time, emissaries of 195 nations signed a pact designed to limit greenhouse gas emissions through a global regime of transparency and accountability. But the Paris Agreement will not by itself deliver the world from auto-destruction.

Across the globe, the prospect of ecological apocalypse has spawned a new genre: climate change art. To coincide with the Paris Agreement, the Berlin-based artist Olafur Eliasson and Minik Rosing, a professor of geology at the Natural History Museum of Denmark at Copenhagen University, arranged 12 miniature icebergs in the Place du Panthéon in Paris that melted over a 10-day period, dramatizing the dwindling Greenland ice sheet. As climate change is a global catastrophe, it has impelled artists on every continent to address the social, political and ecological implications of a warming planet, from Minerva Cuevas in Mexico to Geert Goiris in Belgium to Leon Cmielewski and Josephine Starrs in Australia.

In New England, climate change art has been infused with a regional flavor, a cocktail of eco-aesthetics inflected by the transcendentalism of Ralph Waldo Emerson and the veneration of the sublime practiced by the Hudson River School. The sea permeates every aspect of life in New England, and there is a centuries-long tradition of depicting the lethal power of rough water, as in Winslow Homer’s The Fog Warning. In recent times, New England has emerged as a hub of climate change research and eco-activism, due in part to the galaxy of universities and liberal arts colleges across the region.

It is perhaps no surprise, therefore, that many New England climate change artists are well-versed in matters of public policy and have endeavored to effect social change through a variety of tactics. This is not a cohesive movement so much as a constellation of like-minded practitioners who have conscripted a range of materials and methodologies. This cadre of artists inhabits the nexus of art, science, exploration and activism.

“Global warming and climate change are vital to our planet’s survival [and] addressing it is a priority,” said Lisa Reindorf, an artist and architect in Newton, MA. “Artists have the ability to bring together scientific and creative disciplines and interpret data and information through creative insight and vision.”

Much of her work addresses the obliteration of the natural world to make way for cities—and the obliteration of cities by the natural world. “There is an inherent conflict between nature and building,” she said. “Nature has created its own systems, and anytime we build or put in infrastructure, we’re interfering with that…Not only are we adversely impacting the environment, but there is a counter-pressure. The environment strikes back.”

In Fragile City (2016), part of her series called Interrupting the System, Reindorf presents an aerial view of a partially submerged coastal city in a mixed-media composition on a metal panel. Much of the work is given over to grids and rectilinear geometries in a warm palette of fuchsia, coral and tangerine, but one corner of the imagined metropolis is inundated by water. The deluge heralds entropy and chaos: Some of the squares have been unmoored from the grid and are floating out to sea.

Lisa Reindorf, Toxic River, oil on metal, 64 x 96″.

The seductive spectacle of this apocalyptic cityscape touches on another distinctive characteristic of New England climate change art: the sublime. The manifestations of a warming planet, from coastal flooding to forest fires to violent storms, induces a delectable dread, an intoxicating brew of horror and rapture, as we contemplate the end of the world.

“Nature is full of delight and darkness, energy and decay, life and death,” said Resa Blatman, an artist based in Somerville, MA. “I endeavor to make work that offers me, and the viewer, an elegiac and seductive visual feast, with hints of surrender—surrender of the self, surrender of the natural world, surrender of the things we cannot control.”

In 2015, Blatman was one of 29 artists, writers and poets who sailed along the west coast of Svalbard, a Norwegian archipelago north of the Arctic Circle. During the month-long expedition, the artist hiked on glaciers, boated in and out of fjords and collected detritus—fishing line, fishing nets, combs, toothbrushes—washed up on the shore.

“My muse ended up being the ocean…” she said. “Water will be our biggest issue as the planet continues to warm—both in the negative effects of sea-level rise on coastal areas and the lack of fresh drinking water for our current and growing population.”

Upon her return, Blatman created The Water Project / Rising Tide, a series of large-scale installations made from hand-cut Mylar painted with latex. The third iteration in the series, on display in the atrium of the CHA Somerville Hospital, is a monumental sea-swell flecked with foam and laced with seaweed. The pliable material is puckered and crumpled, simulating the sinusoidal motion of the sea.

For Ellen Alt, a mixed-media artist who divides her time between Boston and New York City, the sight of polar ice melting is “simultaneously riveting and ruinous, gorgeous and ravishing, inspiring and catastrophic.” Like Blatman, Alt recently embarked on an expedition to Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve, in Alaska, to bear witness to the melting ice. Alt makes sense of the sublime—the hypnotic beauty of melting ice, volcanoes and wildfires—by distinguishing between the aesthetics of disaster and the semantics of disaster. “It depends which part of your brain is watching it,” she said. After a trip to Baku, Azerbaijan, where she encountered Kufic petroglyphs at the 15th-century Palace of the Shirvanshahs, Alt initiated Ice Writing, a series of mixed-media compositions in which linguistic fragments are revealed in the melting ice.

In Ice Writing: Warming (2016), a cluster of ice floes seen from above resembles a hybrid of Gaelic script and Ilythiiri, an invented language from the Dungeons and Dragons universe. This glittering archipelago is indecipherable, perhaps a warning from a lost civilization. “There is no readable message in the writing,” she said. “We may or may not understand, and by the time we do, the writing may have melted away.”

Like Alt, DM Witman has developed an expedition-based practice, but she has “traveled the earth via the internet,” she explains on her website.

In February 2014, the Maine-based artist read an op-ed by Porter Fox in the New York Times that foretold a snowless future. By mid-century, it is possible that only 10 of the 19 cities that have hosted the Winter Olympics will be cold enough to host them again.

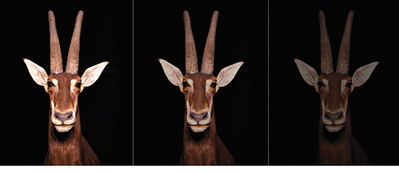

Christina Seely, Next of Kin: Sable Antelope (Hippotragus niger), 2016, kinetic light box, 30 x 40″.

Witman then mounted a digital expedition, visiting each of the former Olympic sites with Google Earth Pro, and printed satellite images of the snowy peaks on salted paper, a medium in which prints begin to fade as soon as they are exposed to light. In one image of the Fitzsimmons Range, outside Vancouver, snowy peaks are inscribed with a rectangular grid, a wilderness to be mapped, settled and exploited.

For her, it’s not just a matter of ecology and economics, but one of morality. In the fall of 2015, she mailed about 250 hand-printed postcard-sized images to a random selection of households in Maine. To view the postcards, recipients were required to remove them from light-tight black poly envelopes, thus initiating the degradation process.

Each mailing contained a description of the project and the attendant moral quandary. “Recipients make a conscious decision as to if and how often to open the envelope which will contribute to the image disappearance. This decision parallels our decisions made daily.”

For many New England-based climate change artists, the aim is not to hector or proselytize, but to stimulate discussion.

“I grew up in Berkeley, CA, where it was normal to be surrounded by strong opinions,” said Christina Seely, an assistant professor in the Studio Art Department at Dartmouth College.

“I learned from this environment that forcing a strong opinion on someone can shut down your audience…With this in mind, I made it an aim not to talk at my viewers through my work or to tell them what to think but instead to more elegantly draw up issues, point to them and leave room for deeper consideration.”

In collaboration with the arts collective Canary Project, Seely has organized an exhibition at the Harvard Museum of Natural History that seeks to provoke a “profound sense of empathy” with extinct and endangered species. Next of Kin: Seeing Extinction through the Artist’s Lens is anchored by a succession of kinetic light boxes in which portraits of at-risk species fade away to reveal the reflection of the viewer. We are witness to the erasure of biodiversity as imperiled species such as the grizzly bear (endangered), the maned wolf (vulnerable) and the jaguar (near threatened) recede into a black void.

The exhibition also includes a set of 10 daguerreotype portraits of vulnerable species that Seely took during expeditions to Greenland, Alaska, Svalbard and the Galápagos Islands between 2012 and 2016. By choosing an obsolete medium associated with the carnage of the Civil War, the artist once again appeals to the empathy of the viewer, forcing her to confront the casualties of our carbon-based economy. As with the kinetic light boxes, the reflection of the viewer in the daguerreotypes implicates her in the annihilation of these species, the degradation of the planet and perhaps the demise of humankind.

“In the first world, we are both incredibly removed from the natural world and natural systems while also inherently connected to them,” Seely said. “Hopefully, [my work] fosters a longing to care for the planet as our survival is dependent on it.”

Christopher Snow Hopkins is an independent writer and critic living in Boston.