Art Under the Microscope: Real or Fake

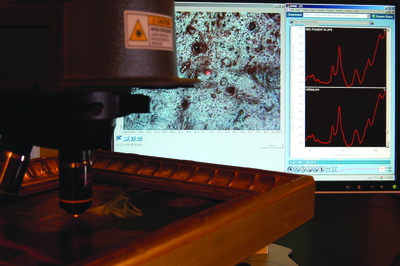

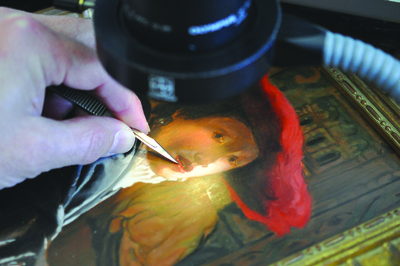

Above: A painting is placed on a Raman microscope for in-situ (non-invasive) chemical analysis of the paint. Below: Removal of a sample from the same painting using a surgeon’s scalpel, while viewing the sample location using a stereomicroscope. All images courtesy of Orion Analytical.

A stone’s throw from the village green in Williamstown, a picturesque New England college town, James Martin runs a business that is rare if not unique in the art world. An artist, art conservator and forensic scientist, he works with law enforcement agencies to uncover art fraud and with art owners and agents to determine authenticity. Others may offer the same professional skills, but not all three in one package.

The head of Orion Analytical, which he founded in 1990, Martin investigates the chemical and structural composition of disputed art objects for the US Department of Justice and FBI and for private collectors, galleries and insurance companies involved in civil litigation. He also analyzes cultural and industrial objects to help conservators and engineers solve treatment problems.

“It’s like a pathologist in a hospital providing a physician with the information she needs to treat a patient,” he says of his work.

Colleagues are less modest in their appraisals: “He is the ‘rock star’ of his field,” says Manhattan attorney John R. Cahill, who specializes in art law and has known Martin for years. “He has no equal. There’s nobody else who can do both the level of chemistry and science and also has the understanding of how the materials are applied and used at a really core level.”

Narayan Khandekar, director of the Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies at the Harvard Museums, adds, “He can sit in court and know all the legal ramifications of what he says and does.”

Martin has been in court often as an expert witness. One high-profile criminal case, which he would not discuss because it is ongoing, involves a Long Island art dealer who sold forged abstract expressionist canvases as originals to recognized Manhattan galleries that resold them to collectors. The fraud was calculated at $80 million.

The dealer, Glafira Rosales, pleaded guilty in 2013 to tax fraud and selling forged paintings and is awaiting sentencing. Three co-conspirators, including the alleged forger, a Chinese immigrant, are under indictment. The galleries that bought and resold art from Rosales—Knoedler & Company and Julian Weissman Fine Art—are facing civil lawsuits, says Cahill, who represents several victims. Knoedler

closed in 2011.

Martin also figured in a noncriminal dispute over the authenticity of a cache of paintings said to be by Jackson Pollock, discovered in a Long Island storage locker in 2002. Several were exhibited as part of a larger Pollock show at the McMullen Museum of Art at Boston College in 2007.

A recognized Pollock scholar initially supported the attribution, the Boston Globe’s Geoff Edgers reported at the time, but Martin and the Straus Center, working independently, concluded some of the pigments tested were not patented until after Pollock’s death in 1956. Viewers at the McMullen exhibition were invited to consider the authenticity question for themselves.

It was a watershed event, Martin says, prompting the College Art Association of art scholars in 2009 to include technical/scientific examination along with stylistic analysis and provenance in its guidelines for authentications and attributions.

Artworks have long been authenticated on their stylistic similarity to undisputed works by the artist and on their provenance, or record of ownership traced back to the artist. But scientific analysis is comparatively recent.

It had its beginnings in the United States at Harvard’s Fogg Art Museum, Khandekar says, when Edward Forbes, the second director, discovered the museum had been sold several forgeries. Forbes started collecting pigments from around the world in 1910 to build a color reference library, and in 1927, he hired chemist Rutherford John Gettens—whom Khandekar describes as “the father of scientific investigation in United States of works of art”—to analyze them. A year later, Forbes established the Straus Center.

It’s impossible to calculate how many honest copies by studio assistants, mistaken attributions or outright forgeries pass as the real thing. Scholars may disagree on attribution, gaps may exist in provenance, even scientific findings can be open to discussion, Khandekar says.

An artwork may test correct in the materials it contains, he explains, but that “doesn’t prove it was by that artist. It can tell you if something is wrong, but it can’t tell you that something is right.”

A known forgery, painted in the style of Max Ernst by Wolfgang Beltracchi. This forgery (of La Forêt (2) by Max Ernst, 1927, oil on canvas) is highlighted in a 60 Minutes report from 2014, in which James Martin is featured as an expert examining the painting.

The consequences of fraud can be far-reaching. Beyond the monetary loss to the buyer, a forgery can taint a private or even a museum collection, casting doubt on the authenticity of other artworks and on the reputations of those who authenticated them. An artist’s legacy and even the historical record can suffer when false information is inserted.

With art market prices at an all-time high, Cahill says the number and sophistication of art forgers is growing. So, too, is the willingness of art owners to sue when the legitimacy of what they’re buying or selling is questioned.

“It’s harder to get an opinion,” Cahill says, “because scholars, even if they have an opinion, are afraid of being sued by the buyer or the seller. Foundations are afraid because fees can be massive to defend themselves.”

Among high-profile artist foundations said to have stopped authenticating artworks are those of Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner, Roy Lichtenstein, Andy Warhol, and Keith Haring. Robert Motherwell’s Dedalus Foundation continues to offer opinions. Jack Flam, foundation president, says, “It’s important to protect and defend the integrity of the artist’s work.”

The College Art Association recommends art historians offer opinions “only when there is a written request by the owner of the work” and then only when the owner promises to indemnify the scholar against legal damages.”

In New York State, Sen. Betty Little introduced a bill in the legislature last year “setting a very high standard for suing art experts,” Cahill says. Reintroduced this year, it is still under consideration.

Martin, 53, married with two children, grew up in Baltimore in a military family. He studied classical painting and drawing methods as a teenager and planned to enroll in a medical illustration program at Johns Hopkins University when he visited the Baltimore Museum of Art on his way to register for classes.

“I bumped into an art conservator, literally, who gave me a tour of the conservation laboratory and told me about art conservation,” he says. “I never made it to Johns Hopkins.”

Instead, he went to Towson University where he earned a bachelor of science degree in studio art with a concentration in chemistry. He got his master’s of science in art conservation at the University of Delaware in 1989.

He taught for two years at the Getty Conservation Institute in Los Angeles, and then joined the Williamstown Art Conservation Center in 1991. While there, he established the country’s first fee-for-service analytical laboratory for museums and conservators without access to scientific analysis. He left the art conservation center in 2000 to launch Orion Analytical.

Today, he works in a light-filled laboratory that could be an art studio, if not for the array of microscopes and spectrometers positioned at spotless workstations. Microscopes magnify objects and samples otherwise too small to see. Spectrometers measure the energy of light interacting with an object or sample.

Martin insists on taking his own artwork samples rather than accepting ones sent to him by clients. And he alone handles specimens in the lab to prevent contamination and assure a chain of custody.

He first conducts a surface examination with incandescent and ultraviolet lights to detect damage, fading, repairs and the ways paints and other coatings are distributed. Then he uses infrared light to search beneath the surface for underdrawings, alterations and faint inscriptions.

Using a microscope, he looks for “adventitious materials” such as strands of fiber or particles in the atmosphere that may be incorporated into the paint.

Raman and infrared spectrometers help him identify the materials in a sample by the spectrum, or line pattern of peaks, they produce. These spectra can be matched with ones produced by known pigments and other materials.

The aim is to determine if all the materials in the painting were available during the artist’s lifetime and if they were applied as the artist would have done. A material developed after an artist’s death, for example, might have been reasonably used in a later surface touch-up by a conservator, but would be suspicious if found in layers the artist painted.

While Martin works with sophisticated devices, he says art buyers armed with only a magnifying glass and an iPad can alert themselves to potential problems by “looking for simple clues that are hiding in plain sight.”

Dirt rubbed across a painting to make it look old is one clue. Circular sanding marks that suggest an old canvas has been scoured and overpainted is another.

An iPad, he says, can be used for on-the-spot Google searches to determine if the gallery that’s offering the artwork or the art expert authenticating it has been involved in lawsuits. A Google image search may also uncover artworks elsewhere that are very similar or even identical to the one in question.

For anyone planning to spend money on art, Martin says, “This is simple due diligence.“

Beyond money issues, authentication can transform an artwork in other ways. When the Clark Art Institute learned last year that a portrait in its collection “attributed to Rembrandt” had been upgraded by a leading Rembrandt scholar as the real thing, Senior Curator Richard Rand observed that, while the artwork itself remained unchanged, the allure of “one of the most magical and revered artists of the 17th century” would attach itself to the painting and transform it into something viewers would hold in deeper reverence.

Charles Bonenti lives in Williamstown and is an art critic for The Berkshire Eagle. He is a regular contributor to Art New England.