Curating New Conclusions

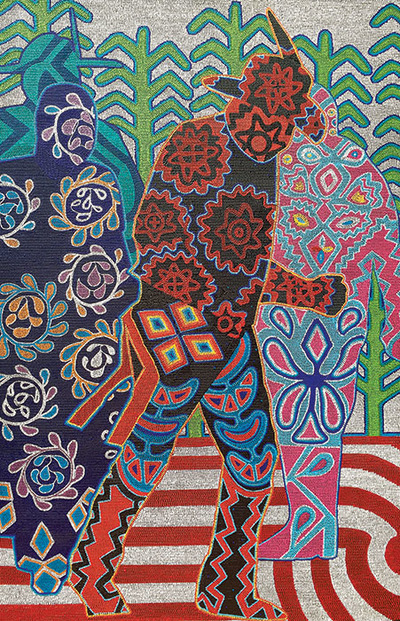

Starr Hardridge, Renewal, 2016, acrylic on canvas, 30 x 24″. Courtesy of the artist.

Courtney M. Leonard’s installation Sustenance 1, on view at the Mashantucket Pequot Museum & Research Center’s Without a Theme exhibit, features harpoon-like spears that hover over a bed of glistening coal that appears freshly purged from the sea. She draws inspiration from elements like water and memory that connect humans, such as the symbiotic relationship between sperm whales and her community, the Shinnecock Indian Nation, located on Long Island, NY. Her installation negotiates many realms, from her personal genealogy to the greater history of her tribal nation, but many of her ideas have the potential to be overshadowed by the audience’s preconceived notions of what Native American work should look like.

Contemporary artists like Leonard often see their Native American background inundate, not inform, their creative message in the eyes of a larger viewing audience; however, organizations are now taking a second look at this dilemma. Until recently, most museums have displayed their Native American collection as cultural artifacts. Curators have emphasized ethnography in compact displays and dioramas, choosing to omit artistic attributions when referencing individual pieces. Consequently, contemporary artists of Native American descent have struggled to break free from these cultural tropes. Yet, news of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s recent decision to exhibit 91 indigenous masterpieces, ranging from the 2nd to early 20th centuries, in a major exhibition in the American Wing suggests a larger change in the landscape. Exhibits are popping up across New England as Native American museums and art institutions recognize the talents of contemporary Native American artists.

Curatorially, it’s not easy to reevaluate existing standards and shift boundaries. There are over 500 active tribes across the United States, and these artists self-identify in differing ways including Native American, American Indian, Alaska Natives, Indigenous, a specific tribal nation or solely as “artist.” So how can curators satisfactorily present the vastness of visual expression in these communities without distorting any viewpoint? The task requires stepping back, rethinking past practices and reaching out to those who are marginalized. Cultural institutions in New England such as the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, MA; the Mashantucket Pequot Museum & Research Center in Mashantucket, CT; and the Abbe Museum in Bar Harbor, ME, are doing just that.

While these organizations have hosted contemporary Native American exhibitions, others are testing the waters of integrating historical artworks into their general American art wings, such as the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, whose 19th-century gallery highlights a water jar attributed to the Laguna Pueblo potter Arroh-a-och (active around 1870–80). The MFA and the Met join the Brooklyn Museum who reinstalled their American gallery last year, incorporating Native American artifacts. “I am excited to see institutions take responsibility to include true American history in the broader sense, and it’s critical that other organizations re-narrate this history,” says Dr. Jason Mancini, director of the Mashantucket Pequot Museum. The over 300,000-square-foot museum combines exhibits and events to connect tribal communities, scholars and the public, such as their annual Indigenous Fine Art Market and residency program for Native American artists—opportunities that are rare in New England but more common in parts of the Southwest and Pacific Northwest due to higher populations of indigenous peoples. Dr. Mancini’s sentiments seem to be echoing throughout New England, yet the Met’s overdue decision reveals there is a long road ahead to truly understanding and supporting the work of contemporary Native American artists on a national and international scale. As a case in point, a number of artists worth mentioning in this article have declined to be included for fear that they would be misrepresented. Many don’t want to be labeled Native American because it typecasts them; they want to be regarded as artists.

Jonathan Perry, Aquinnah Wampanoag, Blue Heron necklace, 2014, slate, copper, glass trade bead, and sinew. © 2015 Peabody Essex Museum. Photo: Walter Silver.

The Peabody Essex Museum (PEM) has long celebrated indigenous art of the past and present, while also looking to its future. They house the oldest collection of Native American items in the country (15,000 artworks alongside 50,000 archaeological objects) and previously assembled the first touring exhibit of contemporary indigenous art and artifacts. “It is great that the Met plans to display their recent gift of works from the Diker Collection within the American Wing. It will be interesting to see how this plays out interpretively. It is one thing to add visual dialogue, but another thing to dig deeper into the complexities—into the entanglements of shared political histories and shared landscapes. The public needs a bridge between the two,” says Karen Kramer, curator of Native American and Oceanic art and culture at PEM. Kramer organized the exhibits Shapeshifting: Transformations in Native American Art in 2012 and Native Fashion Now in 2015–16, which is currently at the National Museum of the American Indian in New York City. She will help lead PEM as they plan for new installations of their Native and American art collections in the Putnam Gallery slated for 2020–21. Alongside PEM’s American art curators Austen Barron Bailly and Dean Lahikainen, she is exploring ways to present these collections together.

Many Native American artists respond to present times while ingeniously honoring and evolving their tribe’s time-honored customs. Jonathan James Perry (Aquinnah Wampanoag), a jewelry maker on Martha’s Vineyard, builds on his ancestor’s intimate understanding of materials and manipulates them into modern designs. Perry’s necklace, Heron Collar, featured in Native Fashion Now, gracefully harmonizes sinew, cold hammered copper, glass beads and a slate pendant inscribed with an abstract depiction of a blue heron. The geometric copper adornments—copper is esteemed by the Wampanoag and its warm reflective qualities are a catalyst for creativity to this day—spread outward like a pair of wings in flight.

The Mashantucket Pequot Museum’s exhibit, Without a Theme, features a new generation of artists whose work rejoices in visual, not cultural, dialogue. Animated shapes and symbols melodiously interplay in the form of paintings, glass sculptures and mixed-media installations. Independent curator Tahnee Ahtoneharjo-Growingthunder wanted the seven participants, each an alumni of the Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA), to contribute their favorite works, allowing a fresh perspective that challenges societal expectations of art made by Native Americans. The IAIA supports indigenous creative rights, while bringing artists to a national and international stage.

Without a Theme’s minimal wall labels and limited context is designed in the hopes that visitors appreciate the work purely for aesthetic reasons. To be labeled Native American means the public will likely discuss the piece under the guise of the artist’s cultural background. This is fine for those Native Americans who choose to align their work closely with their heritage. But for others, who simply want to be known as artists, it makes them reluctant to speak about their work openly. And that’s not the end of the challenges Native Americans face. If an artist is expanding upon creative customs in their work, museums likely exclude showing the pieces if the work contains material from an endangered species. And what’s equally challenging for contemporary Native American artists who create jewelry is how to overcome the assumption that their work should look like Southwestern silver and turquoise. Combined with lingering hierarchical attitudes of indigenous pieces being once considered curios, some still falsely consider Native American art as “craft” or “primitive.” Additionally, says Dawn Spears (Narragansett/Choctaw), a multimedia artist and director of the Northeast Indigenous Arts Alliance, “I don’t think that the Western idea of an artist has ever been in our vocabulary, and it is not a word you will find in our language,” highlighting the constraints of definitions.

Joshua Carter (Pequot/Narragansett) of Wakefield, RI, works in the ancient medium of wampum—a bead derived from shells that reflect the ocean’s sustaining and healing properties. Carter meticulously cuts and sands each tiny piece before he weaves it into intricate designs. “Working with wampum awakens my ancestor’s talent within myself,” says Carter. As he interchanges between centuries-old stone-cutting methods and electric tools, it is another example that traditions are always adapting.

Other artists express their creativity through modern materials and self-designed techniques. Upon researching how his Southeastern tribe, the Muscogee (Creek) Nation, was displaced to the Oklahoma Territories, Starr Hardridge of Redding, CT, renewed his paintings with graphic infusions of Muscogee beadwork and pottery to explore the notions of displacement and perseverance. Hardridge reinterprets these aspects into pointillistic acrylic paintings with subjects that are part personal mythology/part historical influence, flooded in saturated fields of patterned color that converge into rhythmic, mesmerizing designs that reflect a 21st-century aesthetic.

Courtney M. Leonard, Breach #2, 2015, glazed ceramics on wood pallet, 48 x 40″. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Some institutions use contemporary art exhibits to underline current issues within Native American communities. Julia Gray, director of collections and research of the Abbe Museum in Bar Harbor, ME, organizes their galleries using a “decolonization initiative.” The museum, which owns the largest collection of Maine Native American basketry, combines artifacts and contemporary works that function as materials that support one approach to understanding indigenous stories, particularly those of the Wabanaki Nations, who extend from Maine into eastern Canada. The invitational exhibit Twisted Path IV: Vital Signs includes additional programming such as a two-day artist summit that highlights discussions about identity and the physical and mental well-being of tribal nations.

“Curated shows [should] be based on concepts, not sectionalized paradigms,” says Leonard. She also advises accompanying catalogues with writings by exhibiting artists that help the public better understand per-sonal viewpoints.

“Education is key…without acknowledging [Native American art], or respecting it, or supporting it, it will eventually be lost,” urged Perry. As New England museums develop solutions, it seems society already has the tool to break the bias—the artists’ voice. Joshua Carter concludes, “As humans, we are all from somewhere…art is the best way to erase differences.”

Carand Burnet is a poet and creative nonfiction writer. Her work has been listed as a notable in the Best American Essays.