Held to Account

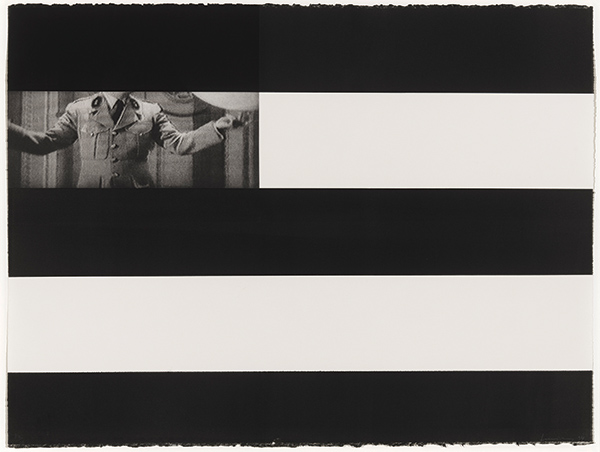

Grainy black and white images. A dictator’s military uniform. Stripes that simultaneously evoke the US flag and a government bureaucrat’s black tape. Such fugitive moments span the five photolithographs from Annette Lemieux’s 1994 portfolio Censor currently on view in her one-woman show Mise en Scène at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. These are timeless images of censorship and repression—abstractions, almost. And yet, just now, to many viewers, they hardly feel timeless at all.

As readers have pushed Sinclair Lewis’s 1935 novel of homegrown American dictatorship It Can’t Happen Here to the top of the bestseller list, it’s worth remembering that the repression of dissident voices has happened here in New England, which has a particularly rich history of limiting what artists can say and where they can show their work. For decades, volunteers in the Watch and Ward Society kept an eye on questionable books and plays. Controversy surrounded the 1896 installation at the Boston Public Library (BPL) of sculptor Frederick William MacMonnies’s Bacchante and Infant Faun, denounced by temperance activists as the depiction of a drunken woman leading a young child down a path to dissolution. The BPL returned the statue to its donor, Charles Follen McKim, who donated it to the Metropolitan Museum of Art (where intemperance was presumably less problematic), and only in the 1990s did the library acquire the replica cast that now graces the fountain of its courtyard.

If the (mostly apocryphal) “Banned in Boston” labels slapped on salacious books by the Watch and Ward Society won New England a reputation for suppression, there were also episodes of resistance, as when Mary Ware Dennett, an artist and designer from Framingham, challenged her prosecution for the 1918 publication of The Sex Side of Life, a rather tame birth control pamphlet. So too, a century ago, activists challenged works of art that distorted and demeaned minority groups in the hunt for fame, profit and entertainment. That was the argument of William Monroe Trotter, a fearlessly uncompromising African American activist in Boston, when he learned that D.W. Griffith’s outspokenly racist film The Birth of a Nation (1915) would be screened at the Tremont Theatre on Boston Common. Trotter convened nearly two dozen public protests that demanded the commonwealth’s restrictive film laws be applied to Griffith’s film. From New York, Roger Baldwin—who would soon establish the American Civil Liberties Union—called Trotter’s position censorship. And today, as artists and writers find themselves on the receiving end of similar critiques, they echo Baldwin’s words. Yet are they really the same thing?

That question came to the fore this spring in New York, when the Whitney Museum of American Art found itself held to account for including in its biennial exhibition the work Open Casket (2016), Dana Schutz’s vividly painted evocation of the 1955 funeral of lynching victim Emmett Till. In an open letter drafted by artist Hannah Black and joined by dozens of artists and critics, the authors argued that “the painting should not be acceptable to anyone who cares or pretends to care about Black people because it is not acceptable for a white person to transmute Black suffering into profit and fun.” “The painting,” they insisted, “must go.” Calls to remove Open Casket (or, as Hannah Black argued, that it “be destroyed”) not only questioned the artist’s motives, but indicted the Whitney’s curatorial process, from which artists of color felt excluded. A biennial “in which Black life and anti-Black violence feature as themes” left Black and her fellow authors wondering whether “this inclusion means no more than that blackness is hot right now.”

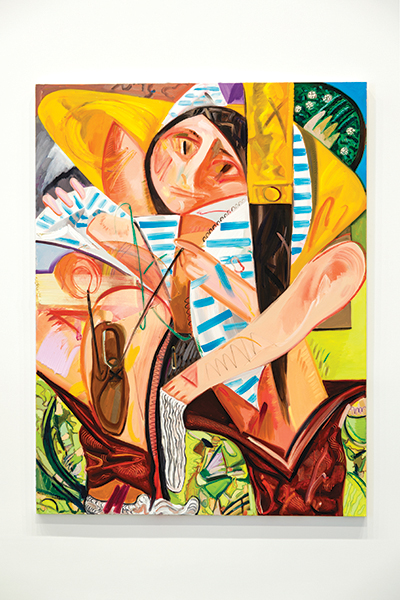

Curatorial process also came under scrutiny at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston as the museum opened an exhibition of Dana Schutz’s recent paintings on July 26, just a few months after the Whitney Biennial. (Indeed, the ICA show’s checklist was confirmed well before the New York controversy, and Open Casket was never planned for display.) Yet the Whitney debate nevertheless reached the ICA when a group of Boston-area artists, students and scholars took to social media and wrote an open letter protesting Schutz’s exhibition in Boston. Left “unconvinced that ICA has the will to challenge the egregiousness of continued institutional backing of this type of violent artifact,” they urged the museum to “[p]lease pull the show.”

A star-studded list of established artists defended Schutz’s exhibition, warning the protestors that it is “of the utmost importance to us that artists not perpetrate upon each other the same kind of intolerance and tyranny that we criticize in others.” In a recent interview, Eva Respini, the ICA’s Barbara Lee chief curator, reflected that the debate was a reminder that museums need to “be transparent about the curatorial process.”

Local critics of Dana Schutz, called to the carpet for “intolerance and tyranny,” were asking for something different. “This is not about censorship,” they explained. “This is about institutional accountability.” Respini, for her part, does not disagree. “Museums need to acknowledge we’re a place of privilege, and try to understand and change that history,” she observed. Interventions at the ICA during the Dana Schutz exhibition included programming, dialogue and context, “giving a platform to a variety of voices and perspectives…as many as we can.” First steps, perhaps, on the route that Hannah Black and her fellow letter-writers mapped, “to live in a reparative mode, with humility, clarity, humour and hope…”

What might that look like? For one thing, it requires attention to process. At Yale University, where the campus echoed last year with calls for renaming buildings, removing public art and reckoning with the university’s past, the first step was to develop transparent, accountable principles for deciding whether to change public spaces and campus art. The Committee to Establish Principles on Renaming carried an Orwellian name yet executed a democratic mission. It ensured that before people jumped to irreconcilable political positions or let a college bureaucrat erase two centuries of history, they begin with a more fundamental question: How will this community decide who we are, what we honor and how our campus structures and artworks reflect both the community itself and the decision-making process we chose?

Yale’s principles and its follow-up committees (which include a Committee on Art in Public Spaces, chaired by painter Samuel Messer) arrived a bit too late to save the campus from its own good intentions. The elaborately detailed exterior of Sterling Memorial Library, constructed between 1929 and 1931, included an architectural feature depicting a Puritan settler aiming a musket at a Native American. Because the corbel—a supporting element—could not easily be removed, university officials simply covered it over with a sloppy dash of stonework. (They have since turned its fate over to consideration by the committee.) They were not the first or the last New England institution to choose silence or invisibility. Dartmouth College is famous for Mexican muralist José Clemente Orozco’s The Epic of American Civilization (1934), while in a nearby building, murals by Walter Beach Humphrey splash cartoonish stereotypes of Native Americans across the walls of a beer garden. Haven’t seen them? You’re not alone. While tourists file past Orozco’s masterpiece, Humphrey’s murals remain awkwardly covered, notionally available to curious students, fond alums and dedicated researchers, but in point of fact hidden and, the college seems to hope, forgotten.

Forgetting is also a risk as Boston dismantles its lone Confederate monument, a granite marker placed on Georges Island in 1963 by the United Daughters of the Confederacy to commemorate 13 men who died in a prisoner of war camp on the island during the Civil War. As cities and towns across the country have removed monuments honoring Confederate leaders, the Boston marker was boarded up this summer. In early October, Massachusetts officials announced the memorial would be removed from its site and stored at the Commonwealth Archives until it can be returned to the UDC.

Governor Charlie Baker noted that symbols like it “do not support liberty and equality for the people of Massachusetts.” True enough, but the people of Massachusetts deserved something better: the participatory process outlined at Yale; the multivocal dialogue aimed for at the ICA; the accountability called for by the open letter writers in Boston and New York. The memorial’s awkward place on state land was an opportunity for context, contemplation and dialogue—about history, about race, about unfinished legacies. Instead, we get a bromide from the governor and a hole in the ground, while the good ladies of Richmond get a stone slab in the mail.

A century ago, when a group of New York artists found themselves and their journal The Masses on trial for sedition, the presiding judge, Learned Hand, assured them that “I do not have to remind you that every man has the right to have such economic, philosophic or religious opinions as seem to him best.” Then, as now, artists and audiences are grappling with the fact that artistic expression is at once more fragile (the artists of The Masses were, after all, convicted) and more dangerous than Judge Hand’s platitude might suggest.

Respini explained that museums are “not courting controversy to get people in the door.” What about the other way around? Will powerful institutions—museums, galleries, universities, municipal governments, preservation commissions—continue to take risks? Or will they quietly choose a slightly less provocative path? The wooden boards that cover the Confederate monument on Georges Island look a good deal like the black stripes in Annette Lemieux’s Censor. How can we make sure they don’t end up doing the same work?

Image 1: Annette Lemieux, Censor (A), 1994, photo etching printed in black and gray, one from the portfolio of five prints. Printed by: Robert Townsend, Harvard University, Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts. Published by: Harvard University, Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts. Promised gift of Richard E. Caves. Courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Image 2: Frederick William MacMonnies, Bacchante and Infant Faun, 1894, bronze, 34½ x 10″. Acquired by Sterling and Francine Clark, 1950. 1955.17.

Image 3: Dana Schutz, Getting Dressed All at Once, 2012, oil on canvas, 73½ x 56¼”. Private Collection. Courtesy of Reiss Klein Partners. Photo: John Kennard. © Dana Schutz. Courtesy of the Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston.