Now What? Plotting the Future

Interior view of the Ogunquit Museum of American Art. Photo: Dan Gair, Blind Dog Photo, Inc.

Museums have developed enormously since private “curio cabinets” went public. The highly professional museum industry currently serves some 850 million people in America annually. More than places for study and research, museums are the public repositories of humankind’s collective cultural capital. They are also wholly local institutions, keyed attentively to the fiber of the communities in which they aim to thrive. As Nick Capasso, hardworking Director of the Fitchburg Art Museum (MA), puts it, “You can tell a lot about a museum when you see who their ‘client’ really is; is it the board of trustees? Is it the big donors? Is it the already established art-going public? Or is it the community within which you are planted? The answer to that question changes your thinking radically.”

Museums today are more than hushed temples of art. Consider Fitchburg’s program title, “UFOs: Unidentified Fascinating Objects.” Its spirit is in keeping with the prominent banner that welcomes the world: FAM is for EVERYONE! It beckons, ¡FAM es para TODOS! In this all-too-familiar New England scenario (a fading mill town) the sign is not only a message of inclusiveness, it conveys institutional commitment to the cultural, economic, and community renewal of a city itself.

“Nonprofits are here to serve people,” emphasizes Capasso, “people who are actually in our community. Many are new immigrants, and there are barriers: linguistic, socioeconomic, cultural expectations. Our goal is to grow a future audience. In programming, we show contemporary work that is relevant, accessible, beautiful, and interactive, and we do so without dumbing it down.” The aim is to become an “engine of creativity, education, community building and fun.” The museum’s recent gallery face-lift, like its partnership with an affordable housing initiative, has wrought valuable change: an uptick in attendance, a broader geographic draw, greater press attention. Public art projects, a focus on contemporary Latino artists (a recent photography project literally put community faces in the permanent collection) and a dedicated community gallery are some of the ways the museum stands by its commitment to lead its community, not merely to be in it.

Transformation is even more dramatic at Maine’s Ogunquit Museum of American Art, in the midst of an ambitious remaking. This beautifully sited small museum just celebrated its 60th anniversary, waking to find itself changed from seasonal sideline to year-round professional museum—quite a contrast from the situation when Executive Director and Curator Ronald L. Crusan arrived. “The year I started, we were [literally] boarded up for the winter!” exclaims Crusan. In five years, the museum has doubled its budget, which has enabled improvement on several fronts: addressing the museum’s infrastructure, raising its profile, and professionalizing its operations. Ogunquit now has a full-time staff of five (soon seven), assisted by a steering committee of three that oversees the recruitment and training of some thirty docents. Program development and an improved website are in progress.

An extensive overhaul of Ogunquit’s physical plant replaced the museum’s spectacular ocean-view window and refurbished a three-acre sculpture garden. Additionally, the museum made quality-of-life repairs—renovating lighting and the roof and overhauling the HVAC system. Not least, it has also accessioned 300 works into the collection, and made strides towards improving the collection management system. Attendance soared with popular exhibitions, evening programs and noontime talks.

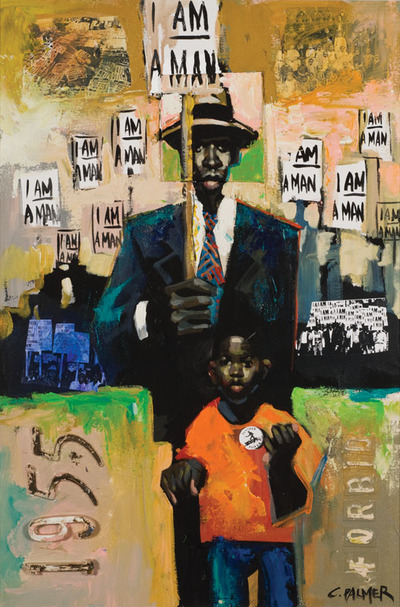

Charly Palmer, A Man from the I Am a Man series, 2006, acrylic on wood with mixed media. Purchase of the 1987 Society of the Amistad Center for Art & Culture. Courtesy of the Amistad Center for Art & Culture.

In Hartford, CT, for the former Amistad Foundation, change is conceptual as much as physical. First, the foundation, now 26 years old, changed its name to the Amistad Center for Art & Culture; second, because its host institution, the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, began a renovation project in its galleries, the center did some soul-searching. Rather than cope with the din, dust and disruption directly upstairs, it closed its own allotted spaces for 2014. “It was a challenge,” admits Olivia White, the Amistad Center’s Executive Director. “Oh, my gosh, we’re going to be closed! But, as always, there was a silver lining—it has taken us to the next level. We had to concentrate on our mission, which has meant creating a true center.”

Closure actually has broadened the center’s community outreach, with exhibitions and programs now dispersed citywide. Closure also necessitated an expanded, more accessible virtual presence to complement an already vital relationship to its community. “What we realized,” says White, “is that although we had an assigned spot in the Wadsworth [its own piece of real estate among the galleries], we did not have a formal presence. Museum visitors might look up and see that the images on the wall were of African Americans, but there was no gateway to signal that they had crossed over. Likewise, for researchers, the means for gaining access to the archives was cumbersome rather that user-friendly…”

“The name change,” says White, “begged the question, ‘Where is the center?’ Our answer had been it’s sort of here, but it’s sort of everywhere.” It is precisely this question that the center has been forced to answer. “What we recognized,” explains White, “is we were given the opportunity to accomplish two legs of our mission. The first element of the strategic plan was to create an identity.” This is exactly what’s in the works: The center is being designated with gateway signage, and operations are being consolidated. The separate entity facility enhances exhibition and research space. “Storage space is being created for the ‘greatest hits’ of our archive, which now will be readily available to scholars,” continues White, “and we’re creating project rooms to accommodate talks amidst the objects.”

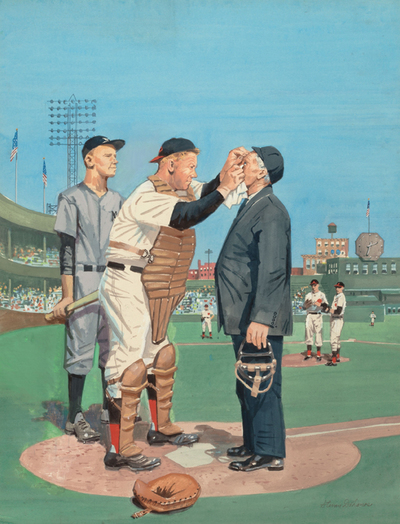

Norman Rockwell, The Umpire—Study, 1960, oil on board, 13½ x 12″. Unused cover idea for Saturday Evening Post. Rockwell used actual ballplayers as the models for this artwork: Batter is Stan Musial; catcher is Joe Garagiola, and umpire is Al Barlick. © 2014 National Museum of American Illustration™, Newport RI. Photo courtesy of the Archives of American Illustrators Gallery™, New York, NY.

For Judy and Lawrence Cutler, founders of the National Museum of American Illustration in Newport, RI, the outlook is likewise bright. Here, programming is comprehensive, even encyclopedic, and the outreach is global. And there’s also the little matter of bragging rights on the exquisite royal flush of its holdings. “Our collection of Rockwell works is second only to the Norman Rockwell Museum [in Stockbridge, MA],” says Lawrence, “But we’ve also got 149 other artists and the finest collection of Maxfield Parrish works in the world!” And he’s confident that the world will continue to beat a path to his door.

Small wonder. Appropriately set in a Gilded Age mansion (Vernon Court, erected 1898), on grounds inspired by Henry VIII’s at Hampton Court and abutted by another park-like tract laid out by Frederick Law Olmsted, this jewel-box of a museum has been adapted (since 1998) to house the “greatest collection of American art” in perpetuity. The collection, amassed and guided by its energetic founders, makes its way around the world—to England and the Far East, where printmaking and illustration, the “most American of American art forms,” as Cutler characterizes it, negotiate their way into the cultural dialogue.

Here is another museum that knows what it’s about, and has stepped forward vigorously to satisfy a global appreciation for a truly American art form that many Americans themselves may not fully credit. What’s new at the museum? Look to blockbuster showings of Norman Rockwell in South London; watch for international programming and print sales in Japan and/or China. With this eminently reproducible of art forms, gorgeous publications and educational initiatives are fostered by this engine of enthusiasm.

In two very different educational settings—the New Hampshire Institute of Art (Manchester, NH) and Vermont’s Middlebury College—growth and reevaluation have led to diverging exhibition philosophies and outcomes. NHIA, a small art school in the shadows of Mt. Monadnock, has grown significantly over the past decade. It is in the process of finding a new president even as it energizes programming and reinvests in its essential mission—to broaden its students’ connection to the greater art world. Since its recent merger with the Sharon Arts Center in Peterborough, NHIA has launched a new low-residency MFA degree (offering studies in Visual Arts, Photography, Creative Writing, and Writing for Stage and Screen).

New programs like the popular Distinguished American Artists Discussing Art (DADA) lecture series bring art world figures to campus and community. An annual event marked by lines forming hours before the doors open is the Minumental Exhibition, to which students, faculty, staff, and alumni submit artwork from all disciplines. Scale is restricted to 2 x 2 x 2 inches, and prices are set at an amusing maximum of $44.95. For the future? “We’d like to engage more with contemporary and historical artists,” says Andrew Lucas, NHIA gallery director. “Currently, most of our exhibitions are for educational purposes, an outgrowth of hands-on student interest and initiative. The school is growing; there’s new energy within.”

Foreground: Robert Indiana, LOVE, 1973, painted aluminum, 6 x 6 x 3′. Collection of Middlebury College Museum of Art, gift of Ken and Linda Wilson; Background: Clement Meadmore, Around and About, 1971, painted aluminum, 7 x 11 x 7’3″. Collection of Middlebury College Museum of Art, gift of Ken and Linda Wilson. Photo courtesy of the Middlebury College Museum of Art.

Throughout the 214-year history of Middlebury College, its Museum of Art has represented not only a calm pivot-point between historical art and a distinguished academic program, it occasionally has been a flashpoint in the sometimes contentious story of contemporary art’s challenge to tradition. Last year, the museum revisited a period of heated confrontation when it resurrected Vito Acconci’s Way Station I (Study Chamber), created when the artist visited in the 1982–83 academic year to teach the class Art in Public Places. This work’s original installation incited a virulent community response that included vandalism and wreckage (torching by unknown protesters in 1984). After nearly 30 years in storage, in October 2013, it was restored and relocated, and now stands among the 22 current and past works of public art at the college. This time, the work has been carefully contextualized, installed in coordination with a retrospective exhibition called Vito Acconci: Thinking Space that boldly locates the significance of its contentious events in the course of Acconci’s career, and the vagaries of conceptual art.

Even this small sampling of New England museums makes it clear that the shift from “curiosity cabinet” to “locus for dialogue” is as driving an impulse as it is diverse in practice. With each museum in the region addressing challenges rooted in the passionate understanding of where they have come from and where they would like to go, they have collectively rolled up their sleeves to confront the task of meeting the contemporary world at eye-level. They are mindfully, passionately, and purposefully turning around their institutions and their communities. In the process, they embrace the full spectrum of what it takes to survive in the midst of cultural, economic, and intellectual sea change. This is New England, isn’t it? That’s how we have always rolled!

Artist and educator Patricia Rosoff passed away on March 25. Please see In Memoriam