Totally Tommy

A few years ago, before Tommy Simpson’s mother passed away at the age of ninety-three, she told him how, when he was a little boy of three or four and being naughty, she would tell him to sit on a chair in the living room for ten minutes to think about what he had done. One time—or maybe it was many times—she came in after five minutes to find he was not serving quiet penitence as instructed, but rather had removed the laces from his shoes and was playing with them.

A few years ago, before Tommy Simpson’s mother passed away at the age of ninety-three, she told him how, when he was a little boy of three or four and being naughty, she would tell him to sit on a chair in the living room for ten minutes to think about what he had done. One time—or maybe it was many times—she came in after five minutes to find he was not serving quiet penitence as instructed, but rather had removed the laces from his shoes and was playing with them.

Simpson tells the story to illustrate how the creative mind will find a way to entertain itself no matter what, but it’s also an apt illustration of this artist’s character.

Simply put, Simpson is irrepressible—he works seven days a week, ten to twelve hours a day, always with several projects, in several media, ongoing at once. The work flows from his Connecticut studio into the attached home he shares with his wife, artist Karen LaFleur, in a veritable Gesamtkunstwerk.

“You walk into his place and you enter an entirely different world,” says Meg White, co-director with Arthur Dion of Gallery NAGA, where Simpson will have a solo show in May. “Every inch is covered and carved,” from the floors to the cabinets down to the doorknobs. “It wasn’t even that clear that we would do something with Tommy until we visited,” she says, but once you’re there, “you can’t help but agree to anything that he wants to put in your space.”

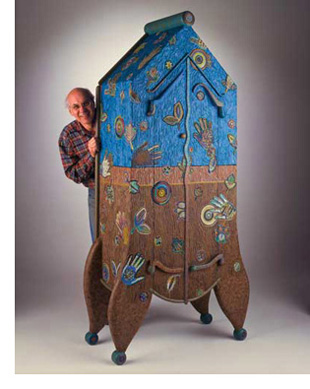

The exhibition, Simpson’s first solo show with the Newbury Street gallery, which has been a supporter and dealer since it featured him in its groundbreaking survey of studio furniture in 1985, will celebrate the acclaimed craftsman’s breadth and output. There will be, according to Simpson: some wooden furniture, some paintings, some ceramics, some prints, some rugs, probably some jewelry, some sculpture. The furniture will range from tables to chairs to dog benches, some painted, some unpainted. There will be some tall, thin jewelry cabinets, and there will be some drawings.

“It’s going to be diametrically opposite of how we install,” says Dion. “We’re spare, with lots of room for each object to capture your attention, undistracted by anything else, and that won’t be possible. It’s going to be a dive into the pool of Tommy.”

“We thought we should give him the show he’s always wanted a museum to do,” Dion adds, “representing every single department in which he works.”

“The object,” Simpson says, “is to show a person enjoying being involved in the arts; it’s more of a person thing than a product thing.”

“A lot of the art world is driven by products,” Simpson continues, but “that’s not my way of doing it. I’m trying to deal with myself, rather than the art market.” In the art world, he explains, “you can be known as the person who does so-and-so,” like Josef Albers and brightly colored squares, “but I don’t find it very healthy for my spirit. I try to work on things I’m really interested in and have fun with, because I think it shows.”

For Simpson, fun is paramount, both for himself and his audience. Irrepressibly whimsical, Simpson’s creations burst at the seams with it. The abstract paintings are brightly colored and frenetically composed; the furniture bears carved sayings or poetry, or animals or characters or symbols, where nary a woodworker would see fit to include them. Enfant de L’Amour, an armchair in mixed wood from 1992, features arms carved to resemble those of a child; framed photographs built into one leg and one upright; rails adorned with a carved heart, moon, star, and knot, respectively; and one upright carved with a face pursed as if blowing air, the rails next to it curved in receipt of the breeze. The seat reads “Enfant de l’Amour,” the top crosspiece is asymmetrical, the front two legs do not match, and attached to the underside of the seat, by a chain skillfully carved of wood, is a slender, freestanding arrow pointing into the earth.

For Simpson, fun is paramount, both for himself and his audience. Irrepressibly whimsical, Simpson’s creations burst at the seams with it. The abstract paintings are brightly colored and frenetically composed; the furniture bears carved sayings or poetry, or animals or characters or symbols, where nary a woodworker would see fit to include them. Enfant de L’Amour, an armchair in mixed wood from 1992, features arms carved to resemble those of a child; framed photographs built into one leg and one upright; rails adorned with a carved heart, moon, star, and knot, respectively; and one upright carved with a face pursed as if blowing air, the rails next to it curved in receipt of the breeze. The seat reads “Enfant de l’Amour,” the top crosspiece is asymmetrical, the front two legs do not match, and attached to the underside of the seat, by a chain skillfully carved of wood, is a slender, freestanding arrow pointing into the earth.

Looking at Simpson’s creations, one thinks of the old chestnut attributed to Coco Chanel: Before leaving the house, take one thing off. For some, there is simply too much going on in his pieces. But for Simpson, it’s all about letting his true self out and encouraging joy and pleasure in his viewer, a goal he finds worthy and much more difficult than the alternative.

“In the last twenty years, the art world has pushed angst,” Simpson says. “Angst is easy. Anybody can stick a knife in a baby. That’s an easy, horrible thing. Trying to make something that’s joyful in spirit” is much harder, he says, and more rare, citing such artists as Paul Klee, Marc Chagall, Joan Miró, Pablo Picasso, Wassily Kandinsky, Arthur Dove, and Charles Burchfield as role models.

Their influence is clear, especially in Simpson’s paintings, which reference Dove’s naïveté, the surrealists’ use of archetypal symbols, and the artfully scattershot compositions and adventurous coloration of Klee, Chagall, Miró, and Kandinsky.

Simpson’s work bears some of the hallmarks of the outsider or naïve art movements: a flouting of the rules of perspective and scale, childishly rendered creatures and other symbols, and a lack of the slickness seen in galleries in major metropolises. But unlike some of the stars of those movements, Simpson’s use of them is an educated, deliberate choice.

Born in 1939, Simpson grew up in Dundee, Illinois. To hear him tell it in his 1999 monograph Two Looks to Home, he had a picture-book childhood straight out of Norman Rockwell. Farm animals mingled with townspeople, kitchen counters always boasted fresh-baked pies, and a ride on the bus cost forty cents. “I lived in the cornfields and the woods and you’d just go out every day and have an adventure,” he says. “I lived on the Fox River, and you’d make boats and get canoes and fish, and it was a wonderful existence.”

Art was never discussed at home, where the talk was more likely to skew toward his father’s medical practice or antique car collection, but Simpson spent a lot of time with his aunt Mary, who would pick wildflowers with him in the woods, and his great aunt Florence, who taught him how to paint them. In school, he was known as a doodler, and around the neighborhood, he handpainted everyone’s skateboard with personalized designs.

“It wasn’t until I was about nineteen that I found out what I’d been doing all these years”—meaning everything from painting to romping in the woods—“was called art,” he says.

Simpson graduated from North Illinois University with a degree in education and went on to earn an MFA in painting at the Cranbrook Academy of Art in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan. He started with printmaking, jewelry, and ceramics at the interdisciplinary institution before switching to painting and sculpture.

Today, he is best known as a leader in the studio furniture movement, Dion says, canonized in the traveling exhibition New American Furniture, organized by the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston in 1989.

But furniture is only one branch of his output, explored initially, Simpson says, “because I didn’t have any,” and pursued because “six out of ten people will buy furniture, but only one or two will buy sculpture.”

While Simpson adheres strongly to his own personal vision, he does vary what media he’s working in partly along with the market for his work—a concession that has allowed him to support himself and his creative needs for nearly fifty years. With six published books, dozens of solo and group exhibitions, two US postage stamps, and works in the collections of such museums as the American Craft Museum in New York, the Renwick Gallery and the Hirshhorn Collection in Washington, DC, and the Boston MFA, Simpson has proven that staying true to one’s vision can pay off.

“I don’t think anyone else could make the sort of work that Tommy makes,” says White. “He always seems in awe of life and what he’s been given, and there’s a real innocence in that.”

Simpson “seems like proof of the contention that all kids are talented, and then they’re taught not to be,” says Dion. “He’s one of those people who seems never to have been taught that.”

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________

Kris Wilton is a freelance writer and editor based in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Her writing has appeared in Modern Painters, Art+Auction, ARTnews, Emerging Photographer, Slate, and the Village Voice, among other publications.