William Kentridge: Calling History into the Studio

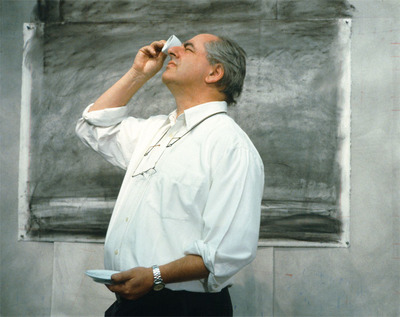

William Kentridge in his studio, Johannesburg, South Africa, 2003

Visiting an artist’s studio is often a disappointing affair: the scrutinizing judge meets the exasperating poseur; artists who’d be better off expressing themselves visually mumble and stumble, as do their puzzled viewers; an entire afternoon can suffocate in the stale odor of turpentine and regret. What a contrast, then, to spend this spring in the studio of South African artist William Kentridge, who presented “Six Drawing Lessons,” the Norton Lectures in Poetry at Harvard University, delivered separately over more than a month’s time. Kentridge’s lessons introduced listeners to his art—a dazzling combination of drawing, animation, and performance—and challenged them to confront, and embrace, what ultimately is at stake in an artist’s studio.

In the last decade, the world has discovered William Kentridge. In 2010 alone, the fifty-seven-year-old Johannesburg-based artist had a retrospective at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, exhibited his drawings at the Louvre, and directed Shostakovich’s opera The Nose at the Metropolitan Opera in New York. That the world has embraced Kentridge reflects the extent to which Kentridge has engaged the world; in his Harvard lectures, he placed his art in conversation with philosophical and creative works ranging from Plato and Rilke to Albrecht Dürer and sculptors of African ceremonial objects.

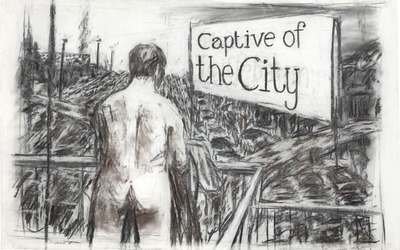

Kentridge is best known for his “drawings for projection,” short, animated films that assemble fragments from the history of art, the history of South Africa, and the artist’s imagination in order to confront the troublesome legacies of the twentieth century. Most memorable is a series from the 1990s featuring the character Soho Eckstein, a fictional Johannes-burg mine owner who eats breakfast, makes money, and confronts mortality in breathtaking but plotless films that depict Soho as the Everyman of modern life. A work by Kentridge is always also a performance; he has drawn on the transcripts of the 1930s Soviet show trials and South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission to stage works that contemplate power and its performance. For Kentridge, who struggled in the 1970s and 1980s to make art under the apartheid regime, politics is inseparable from art—not simply as the subject of a drawing or a film, but because politics imbues every act of looking and each step of the artist’s process.

Through his lectures, William Kentridge impresses on his listeners the political urgency of artistic creation. Asserting “the primacy of the image,” he began his initial lecture with a mesmerizing reading of the ancient story of Plato’s cave. In a world saturated with images—“an endless promiscuity of projection,” as Kentridge put it—we need to free vision from the habits of art and the burdens of history, not by waiting for the emancipating hand of Plato’s philosopher king, but through our own doing. For Kentridge, the search for a democratic way of seeing derives from his art, his reading, and his life in South Africa. That quest happens in his studio, a place he understands as both exalted and ordinary. In “Six Drawing Lessons,” we watched the artist at work. He is sometimes drawing, filming, and contemplating philosophy; other times drinking coffee, walking in circles, doodling, and drinking more coffee.

Like the walls of his studio, Kentridge’s lectures are smeared with charcoal, the artist’s medium of choice. In his films, lines appear and disappear in smudges and erasures like a palimpsest. Charcoal lends itself to the South African landscapes Kentridge depicts; he is drawn to the region’s colorless winter terrain, which is regularly seared by winter fires that coat the veld in charcoal and ash. And charcoal suits the subject of Johannesburg, itself a palimpsest, a boomtown perpetually built and rebuilt on top of gold mines, layers of construction and destruction, remembering and forgetting. Kentridge spoke eloquently of being “disappointed by landscape”: not only a distress at the crimes that took place in these locations, but his sense of disappointment that the landscape cannot be made to remember them. That makes more urgent his drawings, which he executes as “revenge against the landscape.”

William Kentridge, drawing for the film Johannesburg, 2nd Greatest City After Paris, 1989

If Johannesburg’s landscapes do not stand still, neither do William Kentridge’s drawings. In his studio, he draws, then steps away from the work and photographs it. Then he either erases or draws some more, and films again, in a compulsive loop that among other things explains his fascination for early film. (The Georges Méliès 1902 film A Trip to the Moon featured prominently in one of the lectures.) As Kentridge explained in a 1998 interview, “the hope is that…the arcane process of obsessively walking between the camera and the drawing-board will pull to the surface intimations of the interior.” All that coffee-drinking and pacing, it turns out, happens for a reason.

The past is a heavy burden in Kentridge’s work, and much of that weight was on display here: his announced interest in the relationship between “enlightenment, emancipation, and violence”; his account of the suppression of a colonial revolt in the British African territory of Nyasaland in 1915; his reflections on witnessing a racist assault from a car window while riding with his father as a boy; his explanation of the violence inflicted when Africans appear as specimens in natural history museums rather than makers in galleries of art. Kentridge’s talk of the intimations of the interior, together with the reflections woven throughout his lectures about the exhaustion of art in our times, might suggest that his obsession with the studio is motivated by what he describes as a “lack of confidence in action in the world.” Confronted by such history, one might easily crave “a retreat into the studio” as a place apart from problems, whether weighty or mundane. Quite the contrary. The most valuable insight of “Six Draw-ing Lessons” was Kentridge’s insistence on “call[ing] history into the studio.”

Kentridge’s is a daunting intellect, and in less gifted hands “Six Drawing Lessons” could have gone very badly, a weekly appointment with pontification, inscrutability, or oversimplification. But before and after becoming a visual artist, Kentridge has had a life in theater, and it shows—not only as a dynamic and amusing lecturer, but as a thinker deeply concerned with the embodiment of the artist, with gesture and expression, and the generative space between the artist and the audience. If these were drawing lessons, Kentridge made few efforts to draw conclusions. In his final lecture, Kentridge exposed his anxieties: “Do I believe these lectures?” he asked. He means to caution against a naïve optimism in the redemptive possibilities of art. But, whether impishly or insistently (and in William Kentridge’s work there is never any point trying to distinguish the two), there is also an explanation that if what comes out of the studio is implicated in history, it offers much else as well.

William Kentridge in his studio, Johannesburg, South Africa, 2003

So why the studio? There we find an “impure mixture of history, ideas, and materials,” deeply connected to the world around us. As Kentridge points out, his own studio in a lush Johannesburg suburb rests atop miles of gold mine tunnels. But inside the studio is a critical space where history can be productively confronted, by letting “making jump ahead of thinking.” The tragic history of the twentieth century shattered the aspirations of art into fragments, but from the floor of the studio, the artist can pick them up and assemble them, not into their old shapes, but into something new. In 1942, Picasso pulled apart the seat and handlebars of a bicycle to create his brilliant sculpture, Head of a Bull. In “Six Drawing Lessons,” Kentridge shuffled scraps of paper into the form of a horse or a procession of miners, but what he was really teaching was the path into the studio. Summoning Plato in his final lecture, Kentridge explained that “we return ready to enter the cave, ready to cast our own shadows.” And then to go out from the studio into the world again, armed with the very fragments we had once thought to cast aside.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

Christopher Capozzola is an associate professor of history at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.