Window into the Artist’s Mind

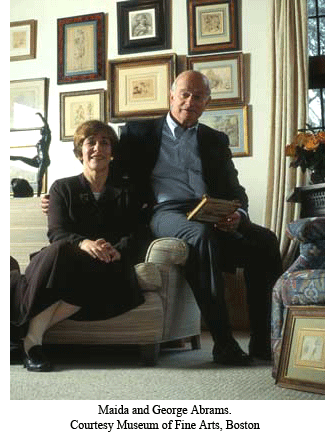

The man who amassed the greatest collection of old master Dutch drawings in private hands is, in several ways, like a character out of one of the works he owns. George Abrams is unpretentious, soft-spoken, and candid, a “what you see is what you get” sort of guy. Not that he’s exactly the kind of peasant or farmer who turns up in many of his drawings. The other side of his life is as a corporate lawyer in Boston, representing some high-powered international clients.

Now in his late seventies, he says he first became interested in the Netherlands because when he was at Harvard Law School, “I spent summers working with a Dutch student organization, helping students to travel and study. I wandered around a lot of Dutch museums. The directness of Dutch art attracted me. There were a lot of everyday scenes, peasant scenes.” Drawings rather than paintings particularly appealed to him “because they show the early stages of the artist’s thinking.”

Now in his late seventies, he says he first became interested in the Netherlands because when he was at Harvard Law School, “I spent summers working with a Dutch student organization, helping students to travel and study. I wandered around a lot of Dutch museums. The directness of Dutch art attracted me. There were a lot of everyday scenes, peasant scenes.” Drawings rather than paintings particularly appealed to him “because they show the early stages of the artist’s thinking.”

The formation of the collection began in 1960 when Abrams and his wife Maida acquired their first Dutch drawing from Boston art dealer Hyman Swetzoff, an early client of Abrams. Abrams’s law practice eventually expanded to include Sonesta International Hotels, which asked him to develop a hotel complex in Amsterdam. That assignment meant regular stays in the Dutch city, where he could track down works he wanted to acquire. When, in 1991, Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum hosted a show of the Abrams’s collection, the couple actually became celebrities of sorts, appearing on Dutch television and even being recognized on the street.

Maida Abrams, who passed away in 2002, was a full partner in the collection: The couple agreed early on that both of them had to like a work before they acquired it. She was also important in her own right as the founder of Very Special Arts of Massachusetts, an organization that advocates for artists with disabilities. Like her husband, Maida Abrams shunned ostentation. She sewed her own clothes, never wore a fur coat, and drove cars until they simply wouldn’t go any more. After his wife’s death, Abrams continued to collect. One of his solo purchases was a drawing by Jan van der Heyden, who, in addition to being an artist, was also Amsterdam’s fire chief and the inventor of the flexible hose. The drawing is a study for a print showing a house fire being extinguished.

When the couple started what would grow into a massive project and a major

passion, “a good Dutch drawing could be had for $1,000,” Abrams says. Now, he adds, “the Getty is buying them, and the price has soared to $500,000 and more.” Rembrandt drawings have fetched more than $3 million at auction. (Dutch drawings are still a relative bargain compared to the $48 million that a Raphael drawing went for at Christie’s auction house in London in 2009, a record for a work on paper.) Ironically, the Abramses’ avid acquisition of Dutch drawings helped drive up the market for them.

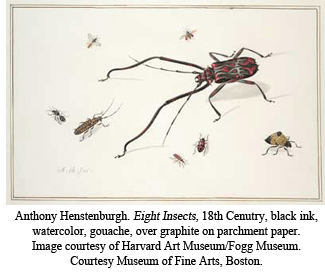

Many of the drawings in the Abrams collection are preparatory studies for paintings, and that freshness and spontaneity appeals to him. Some drawings will have, for instance, several views of a head or an arm in different poses, which gives a clue into the artist’s decision-making process. Drawings are also appealing because of their generally intimate scale, appropriate for a home. As Abrams once wrote, “We loved holding drawings in our hands and looking carefully at those markings in pen and ink, charcoal, gouache, and silverpoint. To see and sometimes possess works by artists who lived and worked 300–400 years ago seemed like a miracle. The finest drawings appeared to exist on two levels, the one material, the other spiritual, a peculiar unity between the expression of something eternal and the fragile being of a small piece of paper.”

On subject matter, Abrams says, “We used to be people collectors.” Hence all the figurative works among their holdings are scenes of people fishing, sewing, farming, gaming, skating, or engaged in other ordinary pursuits. Art in seventeenth-century Holland no longer consisted of portraits of the nobility or grandiose religious scenes. The rising mercantile class had other preferences. Abrams says that after their “people collecting” phase, “We then decided to create a better balance,” adding to the collection delicate landscapes of fields and seascapes that in the space of a few inches seemed to stretch into infinity, as well as drawings of animals, insects, and tulips that reflected the “tulipmania” in seventeenth-century Holland.

When the couple began collecting, “Most American collections of drawings were focused on Italian and French pieces,” George Abrams recalls. That was certainly true of Harvard’s Fogg Art Museum. As an alumnus of both Harvard College and Harvard Law School, Abrams was familiar with the Fogg’s collections. As an undergraduate, he’d even written about Fogg shows for the Harvard Crimson. Eventually, the Abramses gave to the Fogg a bonanza of drawings by the likes of Rembrandt, Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Jacob van Ruisdael, and others, a cache valued at $20 million. The gift instantly made the Fogg the preeminent center for Dutch drawings in the United States. By now, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, also has over 100 drawings given by the Abramses. (For the record, Abrams has collected Dutch paintings as well, of a cabinet size.)

When the couple began collecting, “Most American collections of drawings were focused on Italian and French pieces,” George Abrams recalls. That was certainly true of Harvard’s Fogg Art Museum. As an alumnus of both Harvard College and Harvard Law School, Abrams was familiar with the Fogg’s collections. As an undergraduate, he’d even written about Fogg shows for the Harvard Crimson. Eventually, the Abramses gave to the Fogg a bonanza of drawings by the likes of Rembrandt, Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Jacob van Ruisdael, and others, a cache valued at $20 million. The gift instantly made the Fogg the preeminent center for Dutch drawings in the United States. By now, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, also has over 100 drawings given by the Abramses. (For the record, Abrams has collected Dutch paintings as well, of a cabinet size.)

Among the more flamboyant of their adventures in collecting was one that might be termed “The Chatsworth Caper.” The saga began in 1723, when the Duke of Devonshire bought Rembrandt’s drawing Farm on the Amsteldjik. By 1984, the 11th Duke needed money and sold some of the art that his ancestors had acquired over the centuries for Chatsworth, the family seat in Derbyshire. On July 3 of that year, a sale at Christie’s in London included the Rembrandt, and George and Maida were in the audience bidding. They won. However, the British government was not pleased at the prospect of having a masterwork so long in the hands of a British noble family depart for the former colonies. So they delayed in granting the Abramses an export license. After some months, the British government granted one, thinking that Christie’s might have overvalued the work, making it somewhat less of a national treasure. The license was granted. Abrams made the most of the delay. “By then, I’d had time to find the money,” he once told me.

In 2002 the work made another transatlantic crossing, as one of the stars of the exhibition Bruegel to Rembrandt: Dutch and Flemish Drawings from the Maida and George Abrams Collection, which appeared at the British Museum in London, the Netherlands Institute in Paris, and, finally, at the Fogg. When I interviewed Martin Royalton-Kisch, then the senior drawings curator at the British Museum, about the show, he stood in front of the Rembrandt, gazed longingly at it and, remembering the export license affair, gritted his teeth and said, “It was actually undervalued.”

Unlike, say, an earlier Boston collector, Isabella Stewart Gardner, who relied on art historian Bernard Berenson for advice, George and Maida did their own shopping. The curator most associated with them is Harvard’s William Robinson, who has worked on their collection for over three decades, but it was the Abramses who taught him about Dutch drawings rather than vice versa. George Abrams is such a recognized authority that he has for many years been on one of the vetting committees for The European Fine Art Fair (TEFAF), held every March in the Dutch city of Maastricht. I tagged along one year. Abrams was in his element, schmoozing with other prominent people in the world of old masters.

In the house where George Abrams lives—handsome but hardly palatial—are not only hundreds of drawings but also thousands of books and catalogues. Research and scholarship have always played an important role in his collecting, as have his associations with dealers, curators, auction houses and fellow scholars and collectors. Research pays off. In 1992 the Abramses acquired a drawing attributed to an unidentified sixteenth-century Flemish artist. Two years later, literally on his deathbed, the great scholar Hans Mielke confirmed it as the work of Pieter Bruegel the Elder.

In the house where George Abrams lives—handsome but hardly palatial—are not only hundreds of drawings but also thousands of books and catalogues. Research and scholarship have always played an important role in his collecting, as have his associations with dealers, curators, auction houses and fellow scholars and collectors. Research pays off. In 1992 the Abramses acquired a drawing attributed to an unidentified sixteenth-century Flemish artist. Two years later, literally on his deathbed, the great scholar Hans Mielke confirmed it as the work of Pieter Bruegel the Elder.

The Abramses have always been extremely generous with their collection, lending to a plethora of exhibitions and inviting students and scholars to their home so they, too, can have the thrill of holding a Dutch masterpiece in their hands. On the eventual disposition of his holdings, George Abrams once told me that maybe he should just sell it all back so that someone else could have the fun of amassing it all over. I assume he was joking, and so do a lot of hopeful museums. He does, however, believe that in assembling a great collection, “You’re only a temporary caretaker.”

________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Christine Temin was the art and dance critic at the Boston Globe for over two decades and now writes for a variety of international publications. She has taught at Middlebury College, Wellesley College, and Harvard University. Her most recent book is Behind the Scenes at Boston Ballet, published by the University Press of Florida.