AMBREEN BUTT

Carroll and Sons • Boston, MA • carrollandsons.net • Through December 22, 2012

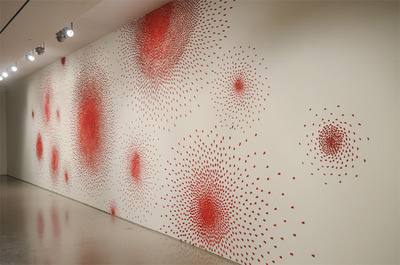

Ambreen Butt, I Am My Lost Diamond, 2011, dimensions variable.

Artist Ambreen Butt takes on extremism in her latest body of work, presented in this solo exhibition. Her subject isn’t extremism itself, but the cultural polarities that force political or philosophical views into a diametrical spectrum of ostensible opposites. Despite the polemical material of her work, however, she claims to dislike politics.

This is not an easy position to take as a Muslim woman born in Pakistan, now living in the United States, where it may be impossible for anyone assigned such an identity to express herself without being politicized. Yet, like her work, Butt resists classification. Identities change and “depend on how the world evolves around you,” she told me.

The concept of one’s surroundings constructing one’s identity drives much of the work in Butt’s show. Extremism exists in a polar system. It can’t exist without the presence of its opposites, while Butt dissolves the space between these binaries. In a diptych with the appearance of a giant open tome, the artist hand-renders statements from opposing sides of a criminal conspiracy trial into two endless vortexes of word fragments framed by classical arabesque patterns. The trial was that of Tarek Mehanna, who is now serving a sentence of seventeen and a half years for charges as dubious as translating publicly available religious texts from Arabic to English. On one page are the words of the federal prosecutor who calls this act material support for terrorism; on the other is Mehanna’s 2,600-word exhortation to the court in which he compares the Minutemen of Lexington and Concord to jihadists and recalls President Reagan’s use of the term “freedom fighter” in order to define the same individuals considered terrorists in our current era.

In another work, Butt draws a dozen portraits that are displayed in a horizontal line. On one end is Salman Taseer, a governor of Pakistan’s Punjab province who was assassinated for opposing the country’s anti-blasphemy law that was enacted under British rule. At the other end is Mumtaz Qadri, Taseer’s murderer, and the ten portraits between them show a slow merging of their two faces (recalling Nancy Burson’s Warhead 1 composite, said to be mostly Reagan and Brezhnev, less than one percent each of Thatcher, Mitterand, and Deng Xiaoping). Butt’s men are “two ends of the same thread,” she told me. In the narrative of history, one can’t exist without the other, and like the converse properties of her Mehanna diptych, each one is at the same time martyr and terrorist.

The largest, most imposing work in the show has less to do with politics than an individual’s experience of extremism. It comprises 25,000 to 30,000 life-size casts, portions of toes, fingers, and feet and entitled I Am My Lost Diamond, hinting at the value of a lost body part. Butt was impelled to create the work (which travels to Tufts University in January as part of Realms of Intimacy: Miniaturist Practice from Pakistan), after a friend narrowly escaped a deadly suicide bombing in Butt’s hometown of Lahore. Close up the work is morbid, but from afar it resembles a delicate pattern of rose petals in three hues from pink to red.

Each of Butt’s works in this show is constructed with the same sensibility of past works that the artist created through the painstaking technique of Persian miniature painting. Whether a microscopic paint stroke or the fragment of a word or toe, each one is an individual mark in an epic work. They draw you in, closely, before they can be identified. They each defy overt appearances, and, though they make bold statements, they also defy classification.

—Christian Holland