Berenice Abbott

MIT Museum • Cambridge, MA • web.mit.edu/museum • Through December 31, 2012

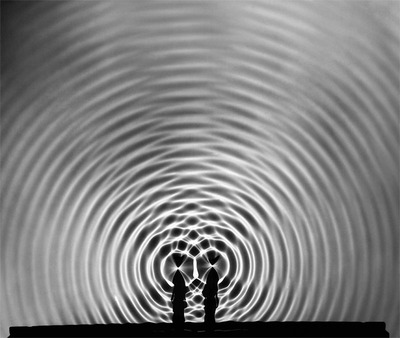

Berenice Abbott, Interference Pattern, 1958-61

Berenice Abbott’s photographs remind us just how much the belief in the veracity of the photograph has diminished. Somewhere in the last half-century it circled back on itself, referencing the act of picture-taking with its exaggeration and propensity for manipulation, invention, and storytelling. Abbott’s emphatic black-and-white photographs return us to the age when photography was valued as a form of evidence, documentation, and rapt description.

This exhibition features Abbott’s photographs of scientific phenomena, a body of work made relatively late in her career and perhaps better known within the scientific than the art community. So it is particularly fitting that it opens the new Kurtz Gallery for Photography at the MIT Museum, where subject matter can be contextualized properly and the broad interdisciplinary approach of the institution brought to bear on a body of work that slips between objective record and pure abstraction and back again. Moreover, MIT is central to the story of how many of these photographs were produced at all.

In 1939, Abbott wrote a manifesto of sorts about the intrinsic role of photography in elucidating the principles of science. It took nearly two decades before she found an outlet at MIT, where the newly formed Physical Sciences Study Committee (PSSC) employed her and gave her a space to work. When Abbott approached Doubleday about a book on her science photographs, the publisher put her in touch with E. B. Little at MIT. Little, a photography enthusiast himself, served on the PSSC committee, organized at MIT in 1956 to reform physics education in American high schools. Abbott made the trek to Cambridge in a snowstorm to meet with Little and pitch her idea, and was hired on the spot.

In 1958, with Russia’s Sputnik looming in America’s immediate memory, Abbott began intensive work to illustrate the principles of physics for a new generation. Her photographs, created in an MIT lab in Watertown and her New York studio, formed the basis of the Image of Physics textbook, brochures, lab guides, and films, and were subsequently seen in a national exhibition toured in the 1960s by the Smithsonian Traveling Exhibition Service (SITES). The current installation is drawn from the collection of Ronald A. Kurtz, a gift to the museum, and includes an original set of the thirty-two enlarged and mounted photographs that comprised the SITES exhibition, as well as Abbott’s early prints of scientific phenomena.

The installation includes wonderful artifacts—reproductions of original wall labels written by critic and Photo League activist Elizabeth McCausland in collaboration with other PSSC scientists, and a pair of road-weary wooden exhibition crates with labels identifying the sender and the shipping cost (.50 cents per pound). It is deep in archival material, including a wall of the widely distributed PSSC physics textbook translated into every imaginable language. There are numerous examples of innovation, as Abbott built contraptions for lighting, design-ed a unisex field jacket for photographers, perfected the technique of shooting ripple tanks by applying the principles of Man Ray’s photogram, hovered above the experiments on ladders, and generally solved an endless stream of problems on how to visualize the laws of physics.

The printed matter shown here, including an enlarged manifesto she’d written while living in New York City while trying to generate support for her early science work, is critical in conveying not only Abbott’s pioneering work but her ability to comprehend the pure exchange of science and photography, one discipline informing another. “There is an essential unity,” she wrote, “between photography, science’s child, and science, the parent.”

Abbott set out to make science poetic, captivating, and alarmingly beautiful. Her images bring evidence of the supreme grace and physical potential of scientific inquiry, illuminated in the elegant arc of a bouncing golf ball, the geometry of momentum, and the terrifying force of a radiating wave pattern.

—Diana Gaston