Claudia DeMonte: Self and The Everywoman

Trustman Gallery, Simmons College • Boston, MA • www.simmons.edu/trustman • Through March 18, 2011

Claudia DeMonte is an artist who starts with women’s experiences and surroundings and explores these aspects in a number of different art media: acrylic painting, bronze sculpture, photography, scratchboard, and painted pulped paper relief.  Coming from a Roman Catholic background in Astoria, New York, she creates work that ranges from religious icons to traditionally female implements: shoes, dustpans, hairdryers, and irons. Working in series, she covers both the universal and the specific. The exhibition at Simmons College (a women’s undergraduate institution), curated by Trustman Gallery Director Michelle Cohen, is particularly appropriate to its milieu. It includes female representations from prehistoric goddesses to contemporary exercise classes with expressive symbols and witty undertones.

Coming from a Roman Catholic background in Astoria, New York, she creates work that ranges from religious icons to traditionally female implements: shoes, dustpans, hairdryers, and irons. Working in series, she covers both the universal and the specific. The exhibition at Simmons College (a women’s undergraduate institution), curated by Trustman Gallery Director Michelle Cohen, is particularly appropriate to its milieu. It includes female representations from prehistoric goddesses to contemporary exercise classes with expressive symbols and witty undertones.

Chronologically, the exhibition starts in the 1970s with a series of photographs by a photographer hired to follow DeMonte around and chronicle her activities. She also created Claudia’s Calendar (1976), which uses photographs of herself and her family and, instead of national holidays, uses family events to mark the days—perhaps a take on the feminist idea that “the personal is political.”

In the 1980s, her works explode with color and reflect art history, such as Fears of St. Claudia (1983) informed by both religious tradition and her own life. In 1988, DeMonte turned to Greek art with a series of amphoras, pulped paper reliefs with vibrant decorations and floral adjuncts as if to feminize a classical mode.

The ’90s saw the beginning of a powerful series in bronze, Female Implements. In these works, most about twelve inches high, DeMonte conjoins female figures with items such as screwdrivers, salad servers, crab claws, and forceps. Some of these figures comment on pain in the female experience, wryly and forcefully. These are domestic goddesses, ones who show women’s experiences in everyday life.

Goddesses take over in DeMonte’s Artifacts series, offering such works as Vesteria and Arani (2007), bronze figures that hark back to prehistoric female fetishes such as Cretan snake goddesses. The modeling of these figures almost shows the artist’s fingerprints, reminding one of Degas’ sculpture: hand-fashioned, informal, capturing characteristic motion, and honoring the female.

DeMonte’s interest in the figure is demonstrated especially in her Camouflage and Scratchboard series (2008), which show small outlined female figures in motion. These representations move into three dimensions in Exercise Class, a series of ten small bronzes of women in exercise positions. These, as the artist points out, are really a representation of luxury and leisure time in American culture in which women overeat and then must take special classes to stay in shape.

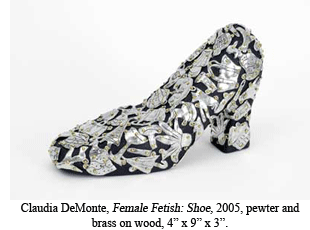

The most powerful and original of DeMonte’s works are her Female Fetishes series of 2002–2008. Here, in their natural dimensions, DeMonte has taken domestic implements and turned them into icons with pewter reliefs on blackened wood in such manifestations as Hair Dryer, Small Iron, and Shoe. Each piece is decorated with small pewter representations of a woman’s world: gloves, purses, tennis rackets, cups and saucers, suitcases, umbrellas. Here the artist combines characteristic feminine artifacts with specific references to her own life and creates amazing icons of female experience with wit, irony, and originality.

The most powerful and original of DeMonte’s works are her Female Fetishes series of 2002–2008. Here, in their natural dimensions, DeMonte has taken domestic implements and turned them into icons with pewter reliefs on blackened wood in such manifestations as Hair Dryer, Small Iron, and Shoe. Each piece is decorated with small pewter representations of a woman’s world: gloves, purses, tennis rackets, cups and saucers, suitcases, umbrellas. Here the artist combines characteristic feminine artifacts with specific references to her own life and creates amazing icons of female experience with wit, irony, and originality.

The exhibition at the Trustman Gallery is one of over sixty solo shows Claudia DeMonte has had. Her work, rooted in her own experiences as a woman, has expanded into global identifications of women from goddesses to fitness mavens. She has investigated and captured icons of female culture in both time and space. Some of these expose the dangers and pain of the female experience, such as the daggers in Fears of St. Claudia and the ominous forceps in the Female Implements series. Her inspiration comes from many sources: antique sculpture, pop art, body art, and feminism, but her voice is distinctively her own, challenging our perceptions and presuppositions of both art and women.

—Alicia Faxon