COMPOSITE LANDSCAPES: PHOTOMONTAGE AND LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE

The more we learn about Isabella Stewart Gardner, the more interesting and complex she becomes. Tiny in stature yet large in her embrace of art and life, she is best known as a collector of old master paintings, though she was also a generous patron of contemporary painters and musicians, a rabid Red Sox fan, a Dante enthusiast and an intrepid world traveler. Among her interests was horticulture and landscape design, the seasonal floral displays in her eponymous museum’s courtyard the most visible evidence of that passion.

Since the opening of its Renzo Piano-designed addition, the museum has programmed exhibitions and events derived from Gardner’s interests; landscape design is an important part of its new identity, and the museum appointed a curator of landscape design, the first in any American art museum. As his first exhibition, curator Charles Waldheim chose as a theme photomontage, a design technique practiced by landscape designers to help conceptualize their projects and to communicate their ideas to clients and the public.

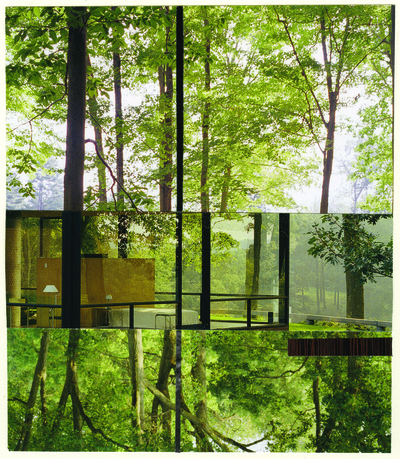

Gary Hilderbrand, Glass House Reflections II, 2012, handcut collage/montage, offset print, handmade paper, 6 x 5″. Private collection.

It is an academic yet nonetheless engaging and informative choice. Waldheim dates the use of montage—“the overlay of one image over another to produce a composite image”—to the 18th century. He roots his show of mostly contemporary works with a few vintage ones, including a photo album assembled by Gardner in which she glued together disparate images. While largely a survey of design work by the profession’s international stars, there are a few artist-made examples of landscape-themed photomontages. John Stezaker’s vintage image of a woman with her profile replaced by a postcard of a cliff and stream is particularly effective as an illustration of the idea and as a work of art.

The design work ranges from the purely artistic like that of Gary Hilderbrand who made lovely collages using photographs of Philip Johnson’s Glass House, to the more practical schemes of Michael Van Valkenburgh for the Minneapolis Sculpture Garden, to the purely conceptual 1970 proposal of the Italian Superstudio for a vast cubic garden in the middle of San Francisco’s Golden Gate. Works on paper are trumped, however, by the digital projects programmed on two large monitors. Colorful, slick, easy to read, they are the profession’s future.