David Driskell: Evolution

Amistad Center for Art & Culture at Wadsworth Atheneum • Hartford, CT • www.amistadartandculture.org • Part I, Printmaking, 1952–1999, through March 6, 2011 • Part II, Printmaking, 2000–2007, March 19–August 7, 2011

In every one of David Driskell’s prints there is a diaspora, though never rendered as a thwarted past. Rather, it is absolutely of the moment, reinventing everything encountered. There is a permanence of ghosts in the lithograph Ancestral Images, The Forest, threading through to the present. Even the common houseplants of Thelma Festival and In the Shadow assert their inheritance of the African landscape. In Ancient Totems, the apparent abstraction is the wilderness overlaid with its own resilience.

Although Driskell’s work from the mid-1950s contains no documentary reference to the ongoing witness of the Montgomery bus boycott, he makes clear that struggle and protest exists here. In Watermelon (1956), the seeds resemble dragons’ teeth waiting for the harvest of violence; in Raven and Owl (1955), the carrion bird is tinted red, perhaps symbolizing wisdom versus death; and in Figures in the Rain (1955) one senses a crowd assembled in a funeral or maybe protest.

Although Driskell’s work from the mid-1950s contains no documentary reference to the ongoing witness of the Montgomery bus boycott, he makes clear that struggle and protest exists here. In Watermelon (1956), the seeds resemble dragons’ teeth waiting for the harvest of violence; in Raven and Owl (1955), the carrion bird is tinted red, perhaps symbolizing wisdom versus death; and in Figures in the Rain (1955) one senses a crowd assembled in a funeral or maybe protest.

Driskell finds material fit for reimagining everywhere, from the comic eyes of Northwest Coast Indian masks in Jonah in the Whale, to the stylized scales of The Fish out of a medieval bestiary, and then the animated geometry of Matisse’s cut paper in Dancer II.

In the series of variations on Eve and the Apple that date 1967–2007, both the brightness and the darkness of the image become progressively more pronounced in later versions, as if the weight of the story grows in its retelling. In each rendering, Eve stretches her hand across her breasts in the modesty learned from the Fall.

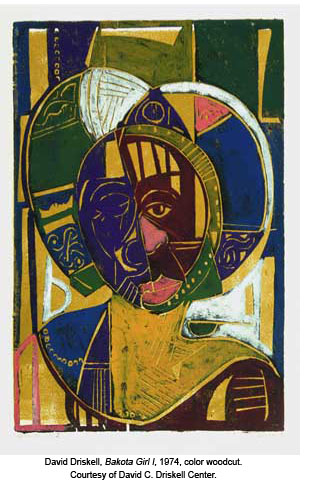

In Bakota Girl, there is the vocabulary of a Christian icon with its variegated halo, as well as the perfection of a mask found in the Head of a Woman (1907) by Picasso, now at the Barnes Foundation. As in Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, the vocabulary of the smaller painting comes from Africa. In Driskell’s woodcut, he returns the image to its origins with cubist transformation intact.

Such a restoration, celebrating what has changed, is characteristic of Driskell’s defining insight that beauty is the companion of justice.

—Stephen Vincent Kobasa