GREENHOUSE EFFECTS: PHOTOGRAPHY BY MARJORIE GILLETTE WOLFE

Stevens Gallery • Homer Babbidge Library, University of Connecticut • Storrs, CT • lib.uconn.edu • Through June 21, 2013

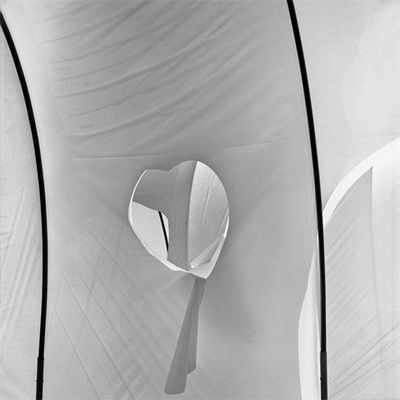

Marjorie Gillette Wolfe, Clinton 14, 2002, archival inkjet print. Courtesy of the artist.

Think of a greenhouse as a machine for shaping light. This is one way in which Marjorie Gillette Wolfe has rendered these workplaces in the series of photographs that she has been making since 1996. The earliest of these, for example, Kurtz Farms #9 and Summer Hill #10, present a vocabulary of recognizable forms for the ongoing subject. The hooped arches with translucent walls sealed against a lowering sky read like prison huts for shadows. The sharp lines of their frameworks, whose arcs are inscribed with the precision of a draftsman’s compass, will be traced again and again as the photographs accumulate.

This entire body of work could function as a lesson book in the investigation of hidden abstractions, with the photograph Blue Brown, Clinton 308 offering a concise visual catalogue of the geometries of tension that these structures contain. It also provides case studies in color saturation, where Wolfe has the subtlest tonalities register with a magical clarity, especially at the thin line that separates the first trace of color from black and white.

Yet the depository of allusions in her work contains far more than merely formal exercises. Boulder might be an Edward Weston nude; in Blue 1, there is an Arthur Dove landscape; and Rose displays a detail of Tintoretto drapery. Other references are architectural, with catacombs and yurts and Romanesque vaults in Clinton 14, 15, and 60. And then there are the suggestions of various media with the dampened and folded paper of Phase 1; the water beading on surfaces in Clinton 408; the carved, tactile presence of Blue 8, the irrational calligraphy of West Tisbury; the collaged, torn arrangements of Blue 3 and Triangular; and the lithography of Snow Greenhouse 3.

Most striking in this thorough documentation of an artificial environment is the boundary work that Wolfe does with these membranes of vinyl and their fragile hold on the space between inside and out. These are the heat treasuries, made to counter weather and calendar in the service of floral commerce. But plastic can go to ruin, too, and its punctured surfaces through which the sky is visible might well offer a means of escape for plant convicts desperate for the risk of the world as it actually is.

—Stephen Vincent Kobasa