ILLUMINATED GEOGRAPHIES: PAKISTANI MINIATURIST PRACTICE IN THE WAKE OF THE GLOBAL TURN

Tufts University Art Gallery • Medford, MA • artgallery.tufts.edu • Through March 31, 2013

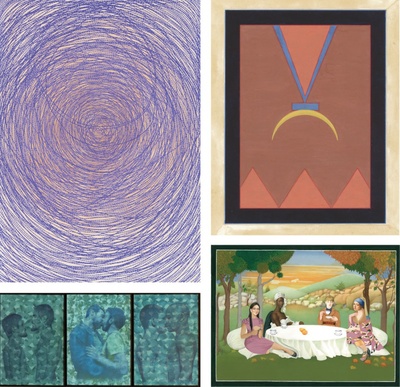

Top left: Ambreen Butt, Call Me a Blasphemy, 2011, paper on tea-stained paper, 57 x 78″. Courtesy of Carroll and Sons Art Gallery. Photo: John Horner Photography. Top right: Murad Khan Mumtaz, Revelation, 2011, opaque watercolor on wasli paper, 18.5 x 18.5″ (unframed). Courtesy of the artist and Tracy Williams, Ltd., New York. Bottom left: Faiza Butt, God’s Best 4, 5, 6, 2011, digital print and ink on polyester film, 33.1 x 23.4″ (unframed). Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Tony Walsh. Bottom right: Saira Wasim, Picnic, 2012, gouache on wasli paper, 14.5 x 10.8″ (unframed). Courtesy of the artist.

In 1918, poet Ezra Pound wrote, “I believe in technique as the test of a man’s sincerity.” He could have been writing about Illuminated Geographies: Pakistani Miniaturist Practice in the Wake of the Global Turn, now on view at the Tufts University Art Gallery. Curated by Justine Ludwig of the Contemporary Arts Center in Cincinnati, Illuminated Geographies builds on Empire and Its Discontents (2008), a pathbreaking Tufts exhibition showcasing contemporary South Asian art, and brings together four artists from Pakistan and its global diaspora who share a mastery of mesmerizingly intricate painting techniques and a passionate sincerity about their art.

South Asian miniature painting is a centuries-old practice that requires years of training. Artists handcraft a smooth and shiny paper called wasli, onto which they apply vibrant paints and even tiny jewels, sometimes using a brush made of a single hair from a squirrel’s tail. This nearly lost art has seen a resurgence in the past three decades as painters trained at the National College of Arts in Lahore maintain and advocate the skills. But Pakistani contemporary artists have not been content merely to replicate old styles, instead using the form to express new visual ideas. As Illuminated Geographies deftly shows, those concepts are not limited to the territorial space of South Asia or even to the cultural traditions of the Indian subcontinent. What began in the 1980s and 1990s as a high-stakes debate among South Asian artists over the terms of tradition and modernity—best known to American viewers in the work of contemporary miniaturist Shahzia Sikander—has evolved into a global conversation about power, identity, language, and artistic practice, articulated here in South Asian idioms.

Saira Wasim uses a lush palette and carefully applied tea washes to generate luminous miniatures in which icons of consumer culture (Ronald McDonald among them) appear where we expect to find the heroes of Mughal sagas. Images of Muslim men in London weave into Faiza Butt’s elusive narratives, which contemplate race and migration, gender and sexuality. Boston based artist Ambreen Butt boldly brings the miniature into the realm of the three-dimensional; her depictions of hands and fingers reflect on the meanings of embodiment even as they remind us of the necessary hand of the artist in her artistic practice. The paintings of Murad Khan Mumtaz are less obsessively detailed than some of the other works; selections from his series Return reflect his engagement with the colors of the American Southwest.

The four artists, all of whom were trained in Pakistan in the 1990s, often show together, obviously borrow from one another’s work, and now comprise the second generation of miniaturist innovators. Based largely outside of Pakistan, in London, Chicago, Virginia, and Boston, they place miniaturist traditions in dialogue with both the social forces of globalization and with the global marketplace for contemporary art. Mumtaz, whose observation that Mughal miniature paintings are about the same dimensions as a passport prompted his Origin, Departure series, provides a provocative meditation on powers great and small.

In looking at Illuminated Geographies, it is worth bearing in mind that the form matters more than the content. Indeed, the form is the content, as these four artists bring a historic art process to bear on concerns that are very much of the present. In the space of the wasli we glimpse the sincerity of the artist, grasp the significance of her technique, and clear our throats to join the conversation.

–Christopher Capozzola