Maine Moderns: Art in Seguinland, 1900–1940

Portland Museum of Art • Portland, ME • www.portlandmuseum.org • June 4–September 11, 2011

American modernism has been a favorite subject of art historians; its many figures—Georgia O’Keeffe, John Marin, Arthur Dove, Marsden Hartley, et al.—make for a compelling draw. What more can be learned about these artists and their time? On the evidence of this nifty exhibition and its expert catalogue (Yale University Press), a great deal.

Putting a place with the somewhat unprepossessing name Seguinland on the art history map is what co-curators Susan Danly and Libby Bischof manage to pull off. This retreat on Sheepscot Bay at the southern edge of Georgetown Island in Midcoast Maine got its name from nearby Seguin Island Lighthouse and from real estate developers promoting the area to turn-of-the-century rusticators.

The Seguinland line-up features many American modernist stars, most notably, Hartley and Marin, Gaston Lachaise, Max Weber, and William and Marguerite Zorach. Add a number of renowned photographers—F. Holland Day, Clarence White, Gertrude Käsebier, and Paul Strand—and you have a concentration of creativity worthy of special notice.

The Seguinland line-up features many American modernist stars, most notably, Hartley and Marin, Gaston Lachaise, Max Weber, and William and Marguerite Zorach. Add a number of renowned photographers—F. Holland Day, Clarence White, Gertrude Käsebier, and Paul Strand—and you have a concentration of creativity worthy of special notice.

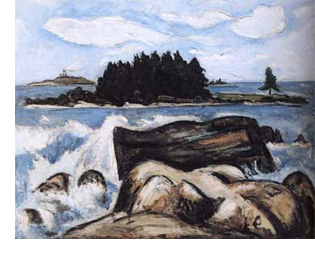

This stretch of Maine coast wasn’t simply a vacation spot for these artists, many of whom traveled there from New York City and vicinity. They produced significant work among the dark spruce and rocky glades. Hartley painted several iconic pieces, including Robin Hood Cove, Georgetown (1938); and Strand began a remarkable series of studies of natural forms while in residence.

Other connections of place and art are less certain, but compelling. The curators suggest that Lachaise may have been inspired to sculpt the stunning Sleeping Gull (1925), the “famous bird” commissioned by poet Hart Crane, during a summer sojourn. Likewise, they argue, Weber’s cubist Forest Scene (1911) may owe its gray-green palette and dynamic shapes to the Maine milieu.

Perhaps the greatest revelation here is the posse of pictorialist photographers that set up camp on Little Good Harbor. Clarence White, who established the Seguinland School of Photography in 1910, and his comrades produced some haunting images. Käsebier’s The Widow (1913) is a spooky soft-focus study of an interior with mother and child; according to Danly, the image did double duty, as an art photograph and a commentary on the plight of indigent women. White evoked classical Greece in his photogravure Boys Wrestling (1908), which features a statue of Pan watching over his nude sons grappling on a sunlit ledge.

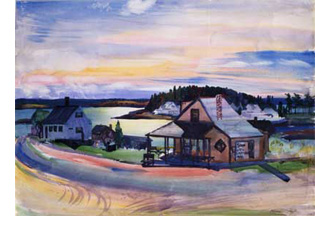

The Zorachs were the most rooted in Seguinland. They bought a homestead in 1924 and made Robin Hood Cove their permanent seasonal residence. William painted watercolors of area motifs and used local granite in his sculpture. He and Marguerite depicted family and acquaintances. The latter’s Clambake (ca. 1945) is a quintessential Seguinland scene.

The Zorachs were the most rooted in Seguinland. They bought a homestead in 1924 and made Robin Hood Cove their permanent seasonal residence. William painted watercolors of area motifs and used local granite in his sculpture. He and Marguerite depicted family and acquaintances. The latter’s Clambake (ca. 1945) is a quintessential Seguinland scene.

Danly, who is curator of graphics, photography, and contemporary art at the Portland Museum of Art, and Bischof, assistant professor of history at the University of Southern Maine, score art historical points in delineating the role the showman Alfred Stieglitz played—from a distance (he never came to Maine). Stieglitz had ties, some of them not so cordial, to most of the Seguinland cast. He makes an appearance in the show by way of a bust by Lachaise (ca. 1925–1928).

The exhibition, which includes major loans from the Whitney, Phillips, Princeton Art Museum, and other collections, is divided between the museum’s second-floor galleries, where paintings and sculpture are displayed, and a recessed space by the first-floor elevator that is custom-made for light-sensitive photographs. Fittingly, Lachaise’s eighty-inch-tall concrete Garden Figure (1935) greets visitors in the main foyer. This statuesque “dryad,” as Hartley called it, once stood on a shaded terrace of the sculptor’s home in Seguinland.

—Carl Little