Olu Oguibe: Wall

Real Art Ways • Hartford, CT • www.realartways.org • Through March 20, 2011

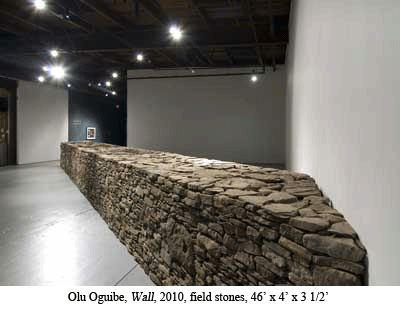

Olu Oguibe creates a stonewall, dividing Real Art Ways’ main gallery in a crisply managed diagonal, in order to establish common ground between minimalism, conceptualism, and environmental art. While the wall fulfills its metaphor, employing an ancient manual craft in an intellectual exercise that is modest, elemental, and pure in form, the effect is more visceral than cerebral, but not by much.

Materially speaking, this installation is a tactile matter couched in verbal puns—stacked stone versus drywall. Though Oguibe compares his work with Andy Goldsworthy’s, his is disappointingly static. One misses the great dialogue of the stone set out in nature with natural light, ice melt, or erosion: “Something there is that doesn’t love a wall…” as Robert Frost might say.

Materially speaking, this installation is a tactile matter couched in verbal puns—stacked stone versus drywall. Though Oguibe compares his work with Andy Goldsworthy’s, his is disappointingly static. One misses the great dialogue of the stone set out in nature with natural light, ice melt, or erosion: “Something there is that doesn’t love a wall…” as Robert Frost might say.

Instead, there is an urban, constructivist spin to this experience. Its dialogue is between the pristine gallery space and the equally pristine form of the chinked wall. Much as it seems out of place in the gallery—marking a diagonal slash across the clean white box of sheetrock (like the slash over the international symbol for smoking)—it also resounds with a certain geometric affinity. The life of the piece is in this contrast, within a defined space without the distractions of decorative paraphernalia.

What is offered is a massive stone barrier. This hand-stacked wall is as perfect a geometric form as anything newly built. Constructed out of gray flats of bluish stone, interrupted occasionally by loaf-like boulders, the weighty mass is faintly powdered with gray dust that sifts and gathers in the myriad of crevices that crackle its sense of mass. It demands to be measured in human anatomy: Its height crowns at the ribcage; its depth stretches as far as you can reach by bending at the waist. The largest of its stones have the approximate bulk of one’s buttocks, the smaller ones the span of a palm. These familiar measures must suffice for nature in this brilliantly white room, just as the hand’s own memory of the touch of stone, coupled with the inhaled dust of labor and the presentiment of tumbledown that inevitably follows human construction, provides a humbling “clock.”

—Patricia Rosoff