Persian Visions: Contemporary Photography from Iran Imagining the Islamic World: Early Travel Photography from the J. Brooks Buxton Collection

The Fleming Museum, University of Vermont • Burlington, VT • www.uvm.edu/fleming • Through May 20, 2012

By turns abstract, edgy, and haunting, the photographs in Persian Visions: Contemporary Photographs from Iran fully transcend the geographic boundaries imposed by the exhibition title. These are not the images that have flashed across American television screens for the past ten years; they’re far subtler than that, muting everyday violence with digital multimedia, blurred focus, and the ever-present veil motif.

Subject matter simmers just beneath the surface, at times brought to a rolling boil by Fleming curator Aimee Marcereau DeGalan’s decision to juxtapose the contemporary prints of the traveling exhibition (toured by International Art & Artists, Washington, D.C.) with nineteenth-century photographs of the Middle East in a complementary show. Photographed entirely by Western photographers, the sepia-tone photographs of camels, galloping Arabs, palm trees, and sculptural architecture were designed to lure Westerners to the East, capitalizing on the nineteenth-century fascination with “the Orient.” The contradictions between these romantically choreographed tourist scenes and the haunting, culturally accurate images of Persian Visions create a conversation-provoking tension that Fleming Museum director Janie Cohen says is vital to the mission of a university museum.

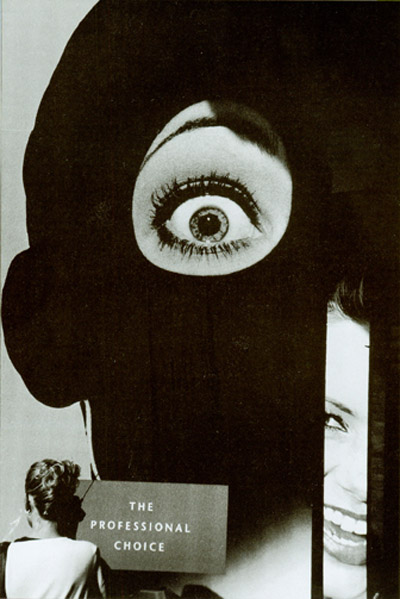

The veil, or chador, is a motif repeated throughout Persian Visions, frequently invoked as a statement of gender politics in works including Koroush Adim’s Revelations series, depicting three women half-obscured by their chadors, or the Barbara Kruger-esque series from Ahmad Nateghi critiquing Western materialism. Other photographers rely on digital manipulation to create a similar effect, such as Kaveh Golestan (killed by a roadside bomb in 2003), whose photographs of a dead girl, a half-charred baby, and bombed-out rubble are shrouded in a red blur that distorts the violence with a visually pleasing glaze.

Diluted by blurred focus or half-obscured subjects, the photographs in Persian Visions largely avoid direct references to war and violence, yet seen in the context of Imagining the Islamic World, the harsh realities of everyday life are made clear. Equally clear is the realization that artistry transcends cultural difference.

—Lindsay J. Westley