TRICKSTER IN FLATLAND: LINDA LINDROTH

Giampietro Gallery • New Haven, CT • www.giampietrogallery.com • September 7–October 3, 2012

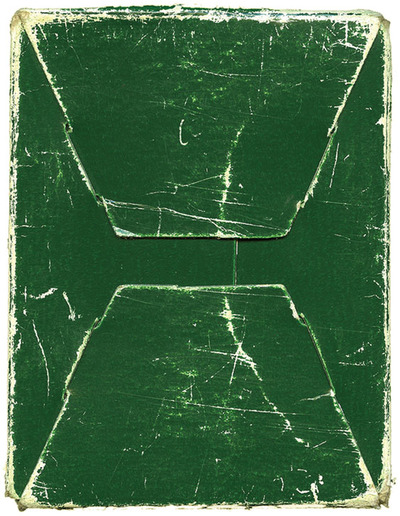

Linda Lindroth, Ellsworth (Green Box), 2011

Giving emptiness a shape is not a small task. As a Samuel Beckett character notes, “There’s no lack of void.” The question of how we define space by the containers we make for it runs through the recent photographs of Linda Lindroth.

What Lindroth does is to compile formulas of three-dimensional geometry using a colorful menagerie of disassembled packages. Reduced to a single plane, they require an act of imagined history on the part of the viewer. What they were when intact is as important as what they are. Lindroth shares some of what Shakespeare called the poet’s gift of taking “the form of things unknown,” and giving it “a local habitation and a name.” The boxes and cartons are signage for the mysteries of form, like origami in reverse, or recycling as subject as well as medium—the traditional garbage of packaging become transcendent waste.

In Elsa (Pink Schiaparelli Box) with its delicate maps of wear, the slightness of shadow along three of its sides edges into a third dimension, marking that permeable boundary between material and absence; Totem (Wrappers) in red and white reads as visual instructions for a pattern of folding and insertion; and Le Contact (Box with Yellow Borders) is an accidental collage where patterns of repair are the surviving traces of missing volume.

For all its homage to a Motherwell painting, there is something in Elegy, Robert that can be strangely reimagined: a pattern on a box of Victorian cereal from which a child might fashion toy coffins or a miniature hearse? Automatic Drawing (Pastel Box) is the floor plan of an Imperial Roman villa that reveals, like the strata of an archaeological dig, a history of its use in the marks of chalk and crayons it once held. Ellsworth (Green Box) retains in its folded form a diplomatic pouch scratched and worn from clandestine travel, or a large tropical leaf pressed into a memento of malaria season.

Other of these varied images are punctured openings that turn a flat surface into a paradox, masking tape like permanent shadows, and a topography of glue, all evidence that, contrary to King Lear, something striking indeed can come of nothing.

— Stephen Vincent Kobasa