10 Emerging Artists 2025

Art New England’s Annual Highlight of Ten Exceptional Emerging Voices

The Emerging Artist feature is one of Art New England’s most impactful traditions. Over the next ten pages, you’ll be drawn into the imaginations, processes and aspirations of ten artists whom you may be learning about for the first time. We offer you a window into their work, knowing you’ll want to learn more. This year’s artists carve, write, dance, paint, weave, make films, design jewelry, throw pots and make cheese. Each year we marvel at how much we learn from these voices and how much bigger the world seems. And when has it ever been more important to be reminded that art expands our world and helps us make sense of it. Through the eyes and hands and words of these ten artists—as well as through the passion of their nominators—we are offered the gift of fresh perspectives, fascinating thought-processes, and outrageous hopefulness. We are challenged by their questions and demands of themselves and of society. And we are relieved to know that there is so much brilliance at work.

Art New England is excited to celebrate: Alison Croney-Moses, woodcarver; Amy Rowbottom, cheesemaker; Zach Raley, painter; Tiffany Vanderhoop, Haida weaver/jewelry maker; Fermin Castro, sculptor; Erin Trahan, filmmaker; Myles Kercher, dancer; Mckendy Fils-Aimé, poet/educator; Naomi Ferenczy, potter; and John Vo, multidisciplinary artist. Art New England is also grateful to this year’s nominators: Ngoc-Tran Vu, artist, activist and a 2024 Art New England Emerging Artist; Sarah Slifer Swift, director MAGMA (Movement Arts Gloucester Massachusetts); Loren King, entertainment journalist, film critic and Art New England contributor; Almitra Stanley, director of Boston Sculptors Gallery; Michele D’Aprix, winemaker; Beth McLaughlin, artistic director and chief curator, Fuller Craft Museum; Diannely Antigua, Inaugural Nossrat Yassini Poet in Residence, University of New Hampshire; Stephen Procter, Stephen Procter Studios; and Tyler Martin, board member Newport Artist Collective and PR director, CUSP Gallery & Lifestyle. Thank you for your time, collaboration, and for helping Art New England raise these voices higher.

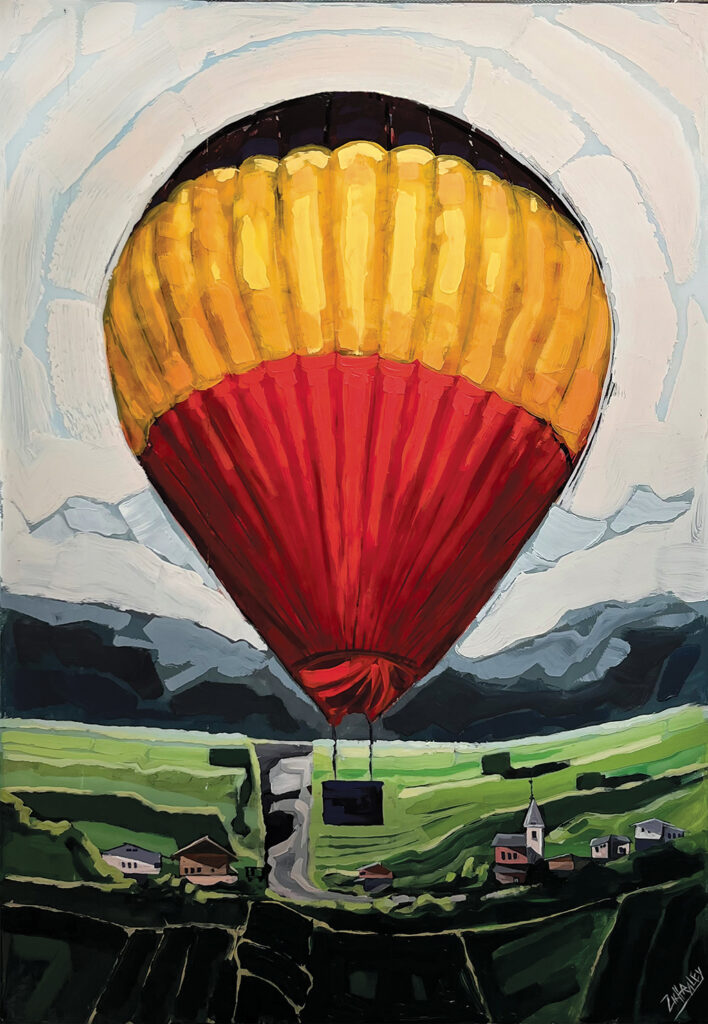

Zach Raley

Needham, MA

raleyart.com

@zachraley_art

Being a part of the Newport Artists Collective, one is surrounded by extraordinary talent on any given day. Walking into the artist salon at the Brenton Hotel on the evening of Zach Raley’s salon, I instantly knew we were in the presence of a young artist who’s on his way to the top of the art world. At seventeen years old, Zach has mastered complex layering of color and texture into his pieces. Whether an inanimate object or a moody street scape that draws you in for a closer look, Zach’s work captivates the viewer, through size, scale, impeccable technique and attention to detail and emotion. — Tyler Martin, board member, Newport Artists Collective & PR director, CUSP Gallery & Lifestyle.”

To Zach Raley, making art is synonymous with eating, sleeping, and breathing. “When I think of art in relationship to myself… It’s a compulsory thing,” Raley says. “It’s not something I like to do—it is part of me.”

As a high school student, Raley’s emergence into the world of art happened at an early age. Raley picked up his first paintbrush in the fifth grade for a class assignment. “I hated everything I made. I was crying. That was the start of the whole thing,” he explains.

From the get-go, improving his craft was central to his motivation. “When I can’t do something, I have to do it and do it and do it until I get really good at it,” Raley explains. “Painting became something I was determined to get good at. I enjoyed doing it and I knew I had to get good at it.”

His interest in the arts stemmed from Raley’s great-grandfather, renowned Armenian-American artist Ariel Agemian. Agemian’s paintings cover the walls of Raley’s grandmother’s Colorado home. “My grandma’s house is filled. It’s basically a museum,” Raley says. “I grew up going to Colorado and seeing all the work.”

After Raley’s emotional fifth-grade art project, he began teaching himself painting techniques. “I haven’t had any specific art education, but I just kept working. I started with Bob Ross paintings and then I moved more into an impressionistic style as time went on.” When Raley discovered artist Kim Rose and her technique of layering epoxy resin and ink, he knew he had to try it. First, he practiced the ink and epoxy technique. “Once I got really good at that, I then applied it to my own painting style,” he shares.

Raley feels drawn to creating not for the final product, but for the creative process itself. “For me, it’s about spending time in my studio and being able to disconnect from everything.” However, people outside Raley’s studio feel drawn to his work. Galleries like CUSP in Newport, Rhode Island, and the Jamestown Art Center’s Salon Series showcase Raley’s emotional, textured paintings of real-world scenes and objects.

This spring, Raley has plans for a few more shows to display his art, which honors his goals of leaving a legacy—a mark on the world. “It makes me feel like I have something that I’m leaving behind, and the more I make and the bigger my work gets, the more I feel like I’m fulfilling that.”

— Maya Capasso

Alison Croney Moses

Boston, MA

alisoncroney.com

@alisoncroney

Alison Croney Moses is one of the country’s most innovative artists working in wood today. With exceptional skill, ingenuity, and precision, Alison brings a sense of care and connection to her creative practice. She combines traditional woodworking techniques, such as hand-carving and shaping, with deeply personal themes and a keen eye for beauty. Her work reveals a deep understanding of her chosen material—one that’s firmly rooted in both knowledge and intuition. — Beth McLaughlin, artistic director and chief curator, Fuller Craft Museum

Themes of foundation and impact emerge when discussing art and the emerging career of wood-carver Alison Croney Moses. For this now Boston-based artist, it all began at home, in North Carolina. “I was always the art kid… My mom was a very creative person who identified as an artist. My sister has that gene, too. There’s a foundation of making. It’s important to acknowledge that it doesn’t come from just me. I have clear memories of my dad teaching me how to draw my first tree. He made some of the furniture pieces in our house, very simple, out of necessity. They grew up in Guyana, where making is very much a fabric of the household and the way of life… I cooked with my mom, sewed hair bows. I remember making two skirts that I wore all the time. I loved them…”

Croney Moses attended Rhode Island School of Design. “I went into graphic design and I hated it. I was bad at it… and switched to furniture design. I had no thoughts to its application in the real world only that I thought I could do it and it looked enjoyable… I switched and I loved it.” Crafting furniture emerged into carving wood.

Smart and self-aware, Croney Moses’ work is grounding and deeply contemplative. In this moment of blind chaos and uncertainty, we yearn for solace and centering which is often found by engaging with art. The focus of Brown Out, her current solo exhibition at Abigail Ogilvy Gallery in Los Angeles, evokes connection, warmth and centeredness. The pieces are made from walnut wood, sourced from a Boston sawmill. “I love walnut, it reflects my skin. There’s a richness to it that I think can be found in brown skin. I see myself reflected in this material.” Our Unit represents family; The Spaces offers sanctuary: “You can’t physically get in there yet visually, you want to.”

After several years in non-profit arts administration, Croney Moses began making art full-time in January 2023. “I’ve always known doing full-time art was an option. It was a choice to work in arts administration because I wanted impact, community impact… From early on it was about young people. I had been working at the Eliot School of Fine & Applied Arts for eleven years before I left to do art full-time. I have always known it was a valid pursuit, that it was a calling of mine…”

And the power of art today? “I think we can take that for granted,” she states. “This is an opportunity to think creatively about impact and how we can achieve impact…” From hair bows to Brown Out, Croney Moses’s impact on wood, young artists and her community is one to watch. As this issue goes to press, we learn that Croney Moses is a recipient of the 2025 James and Audrey Foster Prize at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston which recognizes four exceptional Boston artists.

“How does my art have impact?” she poses. “How does it move people without alienating them? Or maybe it doesn’t matter if I alienate people. I’m gonna alienate some…” Which is just another form of impact and an invitation to explore her work further.

— Rita A. Fucillo

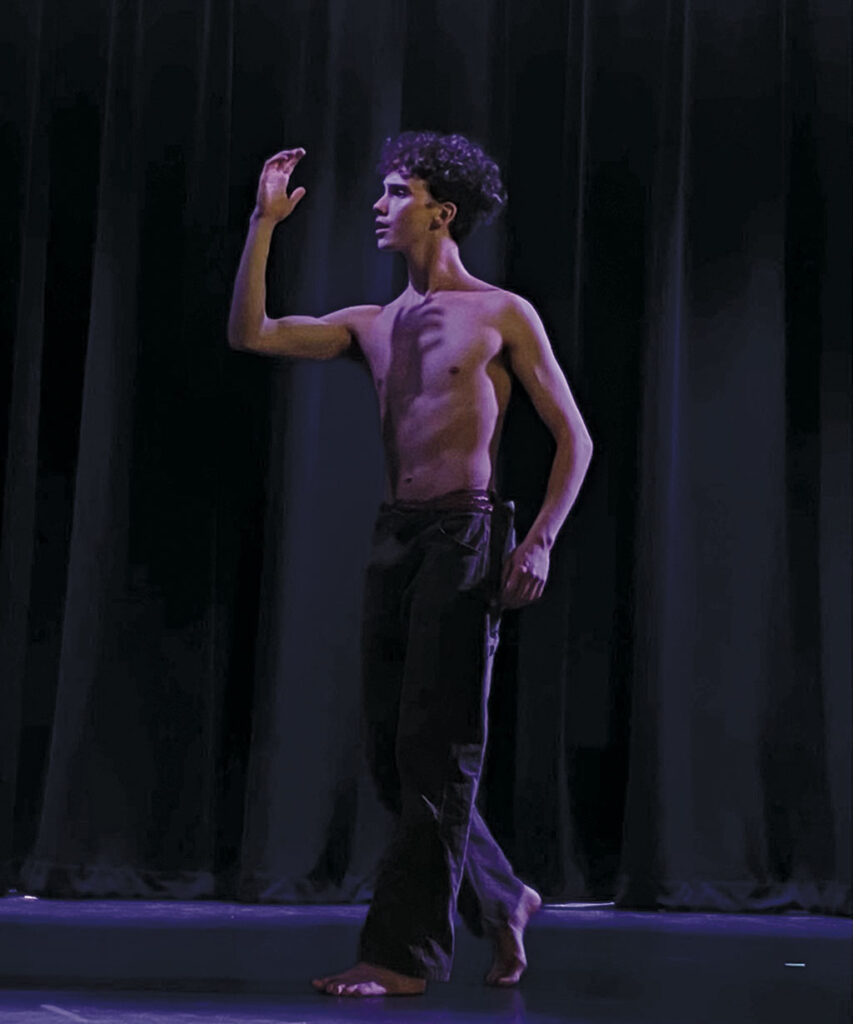

Myles Kercher

Ipswich, MA

@myleskerch

“Myles Kercher is just twenty-one. After an intense ballet training in his high school years, Myles is now reinventing himself as a contemporary dancer and choreographer—and absolutely crushing it! He is a thoughtful artist, allowing his love for visual art, poetry, and music to come through his choreographic voice. His work is physically dynamic and powerfully emotional, exploring that interesting line between theater and dance. He has an extremely bright future in the arts.” — Sarah Slifer Swift, MAGMA (Movement Arts Gloucester Massachusetts)

At just twenty-one years old, Myles Kercher is redefining movement. His work is dynamic, emotionally charged, and deeply human—a fusion of contemporary dance and theater that resonates beyond the physicality of movement. Rooted in an intense ballet foundation, Kercher’s journey has been one of evolution, exploration, and ultimately, self-discovery.

Before dedicating himself to ballet, Kercher’s love for dance was born in improvisation. “I used to go in my backyard and just move to music, exploring movement while playing with props like hula hoops, tap shoes, string, and blankets,” he recalls. While ballet refined his discipline and technical strength, it was during the COVID-19 lockdown that he rediscovered the joy of improvisation, opening the door to contemporary movement. “I was desperate to move and grow, but found ballet on Zoom constricting and frustrating. So, I went back to play and improv… learning Hip-Hop movements, how to isolate my body, and move with more freedom.”

By his senior year, Kercher had immersed himself in the works of Jiri Kylian, Crystal Pite, William Forsythe, Marco Goeke, and Wayne McGregor—choreographers whose innovative styles fueled his passion. “I knew I wanted to dance in their works,” he says, a dream he has already begun pursuing through programs like Arts Umbrella in Vancouver.

While ballet remains an integral part of his technique, Kercher finds power in deconstructing its rigid structure. “Ballet has been my foundation in many ways. I think because of ballet I can reach and create certain lines and shapes with my body that I wouldn’t be able to do otherwise,” he explains. “The biggest influence has been the unlearning of ballet. I love being on the floor, on my hands, my head, my hips. I love exploring more animalistic movements—flailing, crawling, shaking, diving, slithering.”

One pivotal experience in shaping his contemporary path has been his participation in Little House Dance’s Creation Lab in Portland, Maine. “This space pierced my desire to make and move in a contemporary form like no other program has,” he shares. The sense of collaboration and raw vulnerability within this setting cemented his commitment to making work that is unfiltered and emotionally true.

Beyond his own work, Kercher is committed to uplifting emerging artists. “One thing I always want to do within my work is give other young artists opportunities,” he says. His recent collaborations with students from the Boston Conservatory reflect this mission. “I want to be an artist who inspires and mentors others on their creative journeys, as many have inspired and mentored me.”

For those looking to carve their own paths in dance and choreography, Kercher offers simple yet powerful advice: “Don’t give up. There’s a discipline in being passionate and an artist. Perseverance is everything. I promise you there is a space for you and your work.”

As Kercher continues to evolve, experiment, and push the boundaries of movement, one thing is certain—his work will continue to resonate, provoke, and move audiences for years to come.

— Celine Gomes

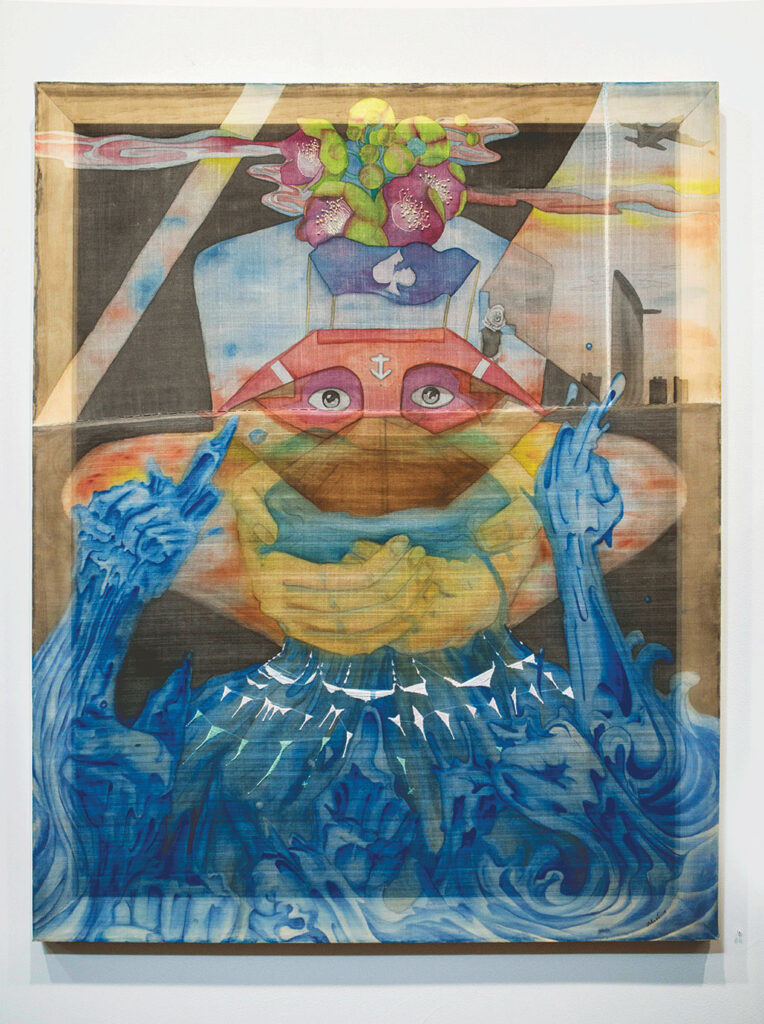

John Vo

Worcester, MA

byjohnvo.com

@by_johnvo

Years ago, I first encountered John Vo’s work as a fellow Vietnamese artist and through his engagement with Worcester’s creative community. Since then, I’ve collaborated with him as a co-facilitator with Artist U and now as a board member at Assets for Artists. His practice seamlessly blends storytelling, craft, and cultural memory, weaving traditional techniques with contemporary narratives to explore resilience and belonging. As both an artist and organizer, John uplifts and inspires through his deep commitment to community and the transformative power of art. — Ngoc-Tran Vu, 2024 Art New England Emerging Artist, multimedia artist and strategic consultant

John Vo was raised in Worcester, MA, and has since returned there, where he lives, works and engages in community organizing with fellow artists. Vo works in silk painting, a technique he was able to study for a year in Vietnam with a Fulbright Scholarship. “My practice primarily revolves around storytelling. I use my parents’ migration story to share that space with others.” Vo’s parents are Vietnamese immigrants from the American war. “I produce work that revolves around the telling of that story from their lens as they try to explore this idea of home.” He uses photographs that survived migration, interpreting them in his own visual language that he has developed here, as an American.

Vo has always shown a proclivity for the arts, something “the adults in [his] life always made space for.” Originally, Vo was driven by a desire to learn about and take ownership of his family’s migration story. He wanted to connect with Vietnam in both the past and the present. Now, Vo is trying to understand what inheriting this story means and what that ownership looks like. “The future work that I am describing now is more about chosen family, this idea of a family, and how it kind of expands into, in a western lens, the people that make up your every day.”

In speaking of his inspirations, Vo stated, “[f]or me, a lot of the inspiration is meeting everyday artists.” He has had the opportunity to connect with other young artists through Mass MoCA’s Assets for Artists, among other community organizing activities. “Growing up, I never got to meet any artists. I’ve always wanted to be this thing, but there was no examples of that. And as I’m becoming an elder in my community, I want to hold that role a little bit.”

Vo’s practice is undergoing some changes. One is that he is moving towards using more recycled products. In the past, Vo would travel to Vietnam every three to five years to collect his silk. Now, he is scouring local recycling plants to build a sustainable practice. True to his word about being inspired by other artists, he explains how Atlanta-based artist Jamal Wright, whom Vo encountered during a residency at Mass MoCA, is changing how Vo approaches his visual storytelling. “A big statement out of [Wright’s] work is that he’s no longer doing figurative work because he doesn’t want to be a part of that story of moving bodies. He wants to create this experience with living bodies in real time and it has really made me think about my work and sensibility, where it’s like, I don’t want to be in the market of selling bodies, or these images of bodies. So, I’ve been thinking about how abstraction and the word ‘figurative’ is an expansive word, and how that can reflect on personhood in my experiences right now.”

Vo is in between studios currently and is working on a new body of work.

— Autumn Duke

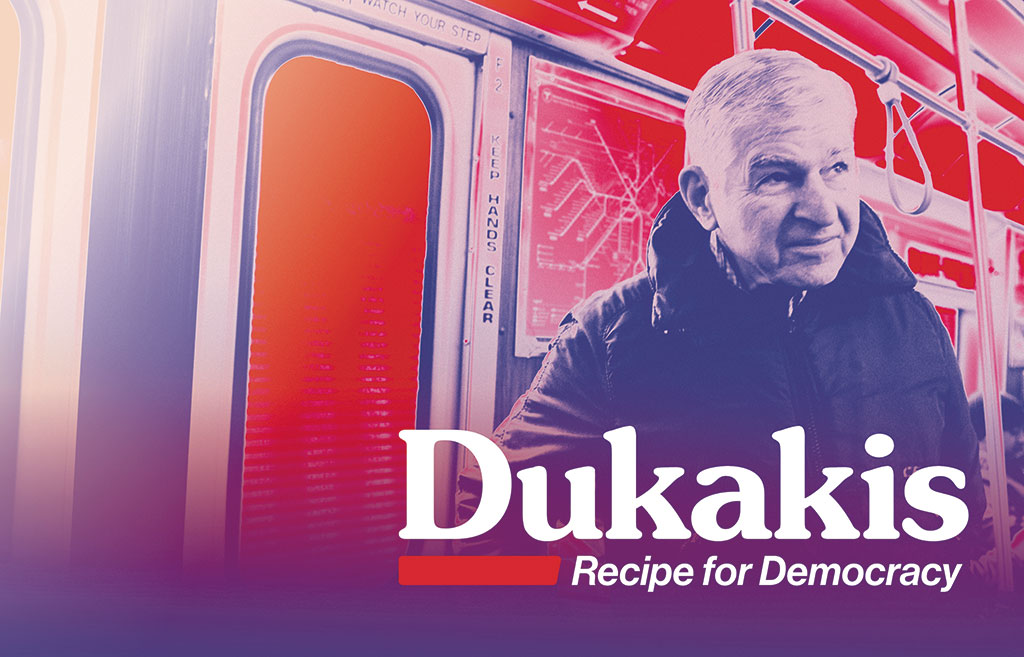

Erin Trahan

Boston, MA

erintrahan.com

I’ve known Erin Trahan as a colleague with the Boston Society of Film Critics and as an active participant in the local film community. I’ve always appreciated her astute and empathetic writing—of course it helps that we share similar tastes in films—but I didn’t know Erin was also a filmmaker. I was thrilled when her first film, Dukakis: Recipe for Democracy, which she co-directed with Jeff Schmidt, was selected to open the GlobeDocs Film Festival last fall. When I interviewed Erin for GlobeDocs, I was impressed and inspired by her humility, dedication and respect for her subject and for the process. Yet I wasn’t surprised. — Loren King, entertainment journalist, film critic

A self-described self-taught journalist, Erin Trahan entered the field in the early 2000s after a career in nonprofit work. Faced with skepticism about “online” publishing, Trahan went for it, eventually adding print, radio, and film to her resume. And teaching: as a faculty member at Emerson College, she offers courses on TV and film journalism. She also co-taught “Creative Expression for Climate Justice” as part of the college’s Transforming Narratives for Environmental Justice initiative.

As a journalist Trahan loves having to become a fast expert on a topic and then translating what she has learned in a way that benefits others. She is especially keen on shining a light on people and stories that may not otherwise get attention.

While attending Notre Dame, Trahan took film study and production. For many years writing about movies “mostly” satisfied her interest in independent media. Wanting to give filmmaking a try again, she found a collaborator in Jeff Schmidt, a Massachusetts-based Emmy Award-winning producer and programmer emeritus of the Salem Film Fest. Together, they made the documentary Dukakis: Recipe for Democracy, which premiered last year.

Asked to pick out a moment in the film that especially pleased her, Trahan chose a scene where the former Massachusetts governor and presidential candidate and his wife Kitty walk their dog through their Brookline neighborhood. In voiceover, Dukakis talks about the importance of knowing your neighbors and establishing a home. “You get a sense of the strength that comes from being rooted,” Trahan notes, “but it’s also him subtly suggesting that roots allow you to flourish, and with that foundation people can better nurture democracy on every level.”

As a creative producer, Trahan is currently working on two documentaries, Impermanence, about the “seemingly contradictory attempt to use ephemeral street art to preserve a crumbling remote, medieval Italian village,” and Lost Village, a first-person film about a woman weighing whether or not to be a mother. Also under consideration is a film about environmental justice, “probably related to limiting PFAs,” and another featuring “a raw, first-person look at a parent’s death and green burial.”

Since finishing the Dukakis documentary, Trahan has returned to an earlier love—poetry (she earned an MFA in poetry at Bennington). Hoping to pull together a manuscript, she compares her pile of poems to “a closet full of clothes” that needs to be sorted through “to create a new ensemble venture out into the world.”

— Carl Little

Fermin Castro

East Somerville, MA

fermincastrosculpture.com

@fermin_castro_sculptures

I first learned of Fermin Castro’s archetypal carved wood sculpture when he applied for a solo show in Boston Sculptors’ LaunchPad Gallery. Considering that he is a self-taught artist who only embarked on a studio practice in 2017, I was impressed with his technical prowess, the sublime surfaces he achieves, and with the iconic beauty and playfulnature of his work. Castro is a talented sculptor and a genuinely warm and generous spirit. — Almitra Stanley, director, Boston Sculptors Gallery

Artistic emergence can take many forms.In sculptor Fermin Castro’s case, a creative passion nurtured quietly over a lifetime blossomed quickly into a full-fledged artistic vocation. Born and educated in Cuba, then moving to the United States, Castro spent years working as a scientist, yet an undercurrent in his life has always been art—from drawing and painting since childhood to a decades-long admiration of works by Afro-Cuban and other sculptors.

In 2017, having finished his science career, Castro taught himself to sculpt in wood. He moved from creating smaller pieces, exploring form and volume, to larger, more intricate abstract figurations, integrating ideas and myths from his Caribbean heritage, as well as themes of evolution and spirituality.

Castro’s pieces entice the viewer to look and contemplate and—just as important—to touch. (He encourages touching the artwork.) Carved and polished with exquisite care, each block of wood emerges smooth and luminous, with rounded organic shapes and, often, suggestions of fish tails, bones, and human forms. In Castro’s sculptures, the interplay of positive and negative space results in an expressive harmony that’s alluring and mysterious.

Castro works with a wide range of wood species (black walnut, red oak, African limba, maple, elm, to name a few), which come from many different, and often serendipitous, sources, like a gift from a friend or a limb from a local downed tree. He keeps sketchbooks filled with hundreds of images that he’s been drawing for years. When a piece of wood matching one of his sketched imaginings presents itself, he goes to work giving shape to his vision. If the wood he’s manipulating offers surprises, like hidden spalting or color variations, he works with it, adapting his approach. This dialogue between artist and material continues until the piece is finished.

Dialogue, language, and communication are words Castro uses often when discussing his work. He considers his pieces (including his paintings, which complement the sculptures) a non-verbal language that enables him to “translate” fantasies and ideas. He wants his work to communicate with those who experience it. And he views his art in a larger context of communication across time and generations, whether through the way a piece addresses ideas of human lineage and inherited stories or in how his work engages in a timeless conversation with past sculptors who’ve influenced him and future artists who’ll encounter his work.

— Alix Woodford

Amy Rowbottom

Skowhegan, ME

orders@crookedfacecreamery.com

@crookedfacecreamery

I met Amy Rowbottom not long after she procured her wine license, a little over a year ago. Amy grew up on a dairy farm and started making cheese in her parent’s barn. Five years ago, she was able to move her operation to the Grist Mill, and after several years of planning, the construction of her new cheese cave was completed in January 2025. This will allow her to expand production.

Amy’s philosophy of honoring and expressing a sense of place, her love of and respect of nature and animals, and her love of community, spoke to what is important to me as a small production winemaker. Amy’s joy in her work is summed up best in her own words: “At the end of the day, after selling cheese and talking to customers and seeing their reaction, it lifts me up, no matter what kind of day I’ve had. It just feels right.” — From Michele D’Aprix, winemaker

There’s a certain poignancy when returning to one’s roots.

Amy Rowbottom grew up on a dairy farm in Norridgewock, Maine, one town over from Skowhegan. She attended college in Massachusetts, yet felt a strong pull back to Maine and family. Returning home, she started making tiny amounts of fresh ricotta cheese in her parent’s barn, working part-time. After a few years, and looking to expand her production, she bought a barn close by, yet a series of life events necessitated a shift in her priorities. While she didn’t have the time to make cheese for several years, her ambition to find her way back to creating never left her heart.

With positivity, determination and faith, Rowbottom returned to her parent’s barn and rebuilt her creamery. Just prior to the pandemic, she signed a lease on a sweet little slip of a shop in the Grist Mill, in Skowhegan, and set her hopes on finally expanding production with ‘Crooked Face Creamery’. Again, she had to pivot and reconfigure how she could really grow her business. She also dug deep, asking herself what was most important.

“As you grow older, you re-determine what you consider success. When I set my sights on opening my creamery and retail in the mill, I thought I would go big, Whole Foods, national placements. The onset of COVID rearranged my thinking, and I realized that going big wasn’t aligned with my values. I had moved back to small town Maine, to the community I grew up in, and I wanted to honor a sense of place and purpose, and focus on celebrating what I do at the creamery as a work of art. I don’t want to change who I am to work with big corporations. You lose touch with why you’re doing it. I realized that my community, my roots, this is everything to me.”

Rowbottom’s entire operation takes place in her little space. Production is in the back and retail out front. Last year, she procured a wine and beer license and offers an intimate, rotating selection of small production wines and local beers. She sells additional products from local artisans, and has hired an assistant in production, retail and accounting—all women, a team of four.

Fresh ricotta has been the “bread and butter” of her business, the engine, the cash flow. When Rowbottom started, she needed a fresh cheese that could sell the next day, to sustain the business. While her dairy of choice has always been cow’s milk sourced from local farmers, having just completed her “years in the works” cheese-aging cave in January, she can now explore the aging process and further evolve as a cheesemaker.

“I finally feel poised to really launch. I have been constantly redefining myself. It’s taken a long time to get where I am, to know what’s important to me, and to better align my work with my values, my family, my resources and my market. I celebrate that small is big. This little store has fed my soul!”

— Paige Farrell

Tiffany Vanderhoop

Shrewsbury, MA

huckleberrywoman.com

@huckleberrywoman

Tiffany Vanderhoop is an innovative artist of Haida and Aquinnah Wampanoag descent, best known for her stunning beaded jewelry. A true visionary, Tiffany creates beautiful, wearable art forms that seamlessly blend generations of tradition with contemporary design and a modern edge. Her geometric beadwork serves as a wearable tribute to the richness of textile arts and the resilience of Indigenous handwork. I’m excited to see what’s next for her! — Beth McLaughlin, artistic director and chief curator, Fuller Craft Museum

Growing up, Tiffany Vanderhoop found herself surrounded by traditional arts. On her mother’s side, she saw her mother and aunties engage in traditional Haida weaving. “My whole family on my Mom’s side are weavers, artists or textile artists. When I was around seven, my aunties taught me how to weave.” Her father’s culture, Aquinnah Wampanoag, brought her in contact with beadwork. “I learned how to bead on a loom when I was a kid in Aquinnah,” Vanderhoop shares.

The amalgamation of Vanderhoop’s Indigenous cultures inspires her art-making. As a teen, Vanderhoop and her sister learned the art of Haida weaving under the careful eye of their mother. While living on the West Coast, Vanderhoop found many delighted customers for her weaving. However, when she moved back to Aquinnah on the East Coast island of Martha’s Vineyard, she struggled to make sales.

That’s when Vanderhoop pivoted towards beadwork. “I wanted to do something that would connect me to my Dad’s family traditions so I started beading,” Vanderhoop explains. “I had been doing a lot of Haida art, dancing, singing, and drumming. It was like a balance between my two cultures to start picking up beadwork.”

Vanderhoop fell into her stride. “I started using design patterns from my Mom’s side, Haida traditional textile weaving geometric patterns, and graphing them and beading them onto earrings. That’s when I really found my niche,” says Vanderhoop. “It was a fun balance between my Dad’s beadwork side and my Mom’s textile side. I really loved the way the patterns translated into the beadwork.”

This combination of art from two different cultures inspired Vanderhoop’s unique style. “I create a graph and I take an ancient pattern that has been used and passed down generations since time immemorial. I translate them into beadwork and I like to think of them as a contemporary way to share these ancient patterns,” Vanderhoop explains.

After Vanderhoop’s brand, Huckleberry Woman, was picked up by the collective B. Yellowtail by Bethany Yellowtail in 2018, Vanderhoop gained more customers and admirers. This visibility allows the artist to further achieve her art’s mission. To her, finding success as an artist means “the preservation of Indigenous traditional arts and sharing to those who are curious,” she says. “Indigenous people are still here, still creating, evolving and modern. We’re not relics of the past, but innovators of the future. I’m thankful my children get to see me sustaining myself in a way that is a continuation of how our ancestors created.”

— Maya Capasso

Mckendy Fils-Aimé

Lowell, MA

Instagram: mr.mack88

Bluesky: mrmack88

X: mrmack88

I first encountered Mckendy’s work when we were both emerging voices in the New England slam scene, two young BIPOC poets with roots on different sides of the same island. Our shared histories and unique narratives have continued to intersect, shaping our present journeys as poets. Mckendy’s debut poetry collection, Sipèstisyon (YesYes Books, 2026), is a powerful exploration of memory, migration, and mythology, intertwining personal and collective histories through the lens of Haitian superstition and the weight of generational trauma. His work—both poignant and fearless—dives deep into the complexities of survival, resilience, and the ghosts that shape us, offering a profound meditation on the stories we inherit and the healing power of memory. — Diannely Antigua, Inaugural Nossrat Yassini Poet in Residence, University of New Hampshire

Mckendy Fils-Aimé is an up-and-coming Massachusetts-based poet. Fils-Aimé began writing poetry in high school and found his voice when he began attending open mic events in Manchester, New Hampshire, where he grew up. “The first couple times I was really shy, so I didn’t really read my poems like that, but eventually I warmed up to it and started reading on the open mic somewhat regularly,” he said. Around this time, Slam Free or Die began hosting poetry slams. Fils-Aimé began reading up on the history of that genre and became more invested in this form of artistic expression. “I started slamming and after a couple years went by, I started doing a little bit well for myself on that scene, regionally, a little bit nationally.”

Getting involved in the slam poetry scene allowed Fils-Aimé to start taking his craft more seriously. New England’s slam scene tends towards the literary, and Fils-Aimé found himself reading the works of Patricia Smith and “other poets who were really giving attention to the page, and so I was at the same time learning about the importance of how a poem shows up on the page, and really trying to work towards improving that element of my craft.” Fifteen or so years later, Fils-Aimé is still doing slam poetry and is under contract for his debut book of poems Sipèstisyon, set for release in 2026.

Of his poetic process, Fils-Aimé said, “Living life is a part of it, right? Just living life and taking in experiences.” When he is not actively writing, he is thinking about writing. “I’m always looking, always thinking about writing and poetry, and always thinking about new concepts I could write about.” Reading is a large part of this process. In addition to online literary journals, which he lists as a great source of inspiration, he lists Blood Dazzler by Patricia Smith, Good Dress by Brittany Rogers, The Big Book of Exit Strategies by Jamaal May, If Pit Bulls Had a God, It’d Be A Pit Bull by Gabriel Ramirez and Best Barbarian by Roger Reeves as current reads.

In addition to his artistic work, Fils-Aimé considers community organizing to be imperative. “I think that the poems can be great, but you have to be a decent person, and also really doing something for your community. That’s something that I think about all the time, and I try and take steps to make sure I’m doing that.” True to his word, Fils-Aimé organizes poetry readings and workshops, works with high school students, co-organizes and consults on writing retreats.

Currently, Fils-Aimé is working on revisions for Sipèstisyon as well as a shorter chapbook centered on Haitian folklore. This chapbook would consider the shapeshifting lougawou “as a vehicle to talk about imperialism, white supremacy, race and other stuff too.” His goal is to finish by the end of the year and, if it feels right, turn this chapbook into a second collection of poems.

— Autumn Duke

Naomi Ferenczy

Brattleboro, VT

@bigpotgirl

At age 22, Naomi Ferenczy is forging her path into the world of ceramics. After distinguishing herself in one of my big pot workshops, I persuaded her to commute from the Hudson River Valley to Brattleboro, VT, to work with me two days a week. After six months, she left for a three-month ceramics intensive course in Barcelona, followed by months of soaking up European culture and art. In spring 2024, I hired her to work with me full-time as my studio assistant. A $15,000 apprenticeship grant from Studio Potter is supporting a year-long professional development curriculum that will culminate in her curating and producing a public exhibition of a new body of her own large-scale work alongside mine. — Stephen Procter, Stephen Procter Studios

It’s remarkable to come upon a young artist who embodies the poise and quiet intention of certainty. Ceramicist Naomi Ferenczy grew up in Coxsackie, NY, a small village in the Hudson River Valley. She took an introductory ceramics course during her junior year in high school, and seeing Ferenczy’s interest, her instructor suggested she matriculate to an independent study, working with clay, during the spring session of her senior year. Ferenczy would build her own syllabus, and create two projects on which she would be graded. Due to the pandemic, she was only able work in the school art room until March of 2020.

Determined to keep producing, and with the gift of a small potter’s wheel from her sister, Ferenczy created a small studio space in her parent’s basement. For two and a half years, she worked as a barista part-time, and worked at the wheel, creating tableware, and selling her work in town. When she learned of a large-

section ceramics workshop in June of 2022 at Stephen Procter Studios in Brattleboro, VT, she enrolled. “I knew I needed to work in an artists’ studio, I needed instruction, to learn technique, and I thought that would be the best way. I actually told a friend when I signed up for the workshop that I hoped Steve might hire me to work at his studio!”

The stars aligned and Procter did offer her a job. For six months, Ferenczy worked in his studio two days a week. She then left for a three-month ceramics intensive course in Barcelona, followed by several months exploring European culture and art. In the spring of 2024, Procter hired her to work with him full-time as his studio assistant.

Last year, Procter and Ferenczy applied for an apprenticeship grant from Studio Potter, an online publication focused on ceramic arts, written by and for potters. Each year, five Mentor-Apprentice teams are chosen. The grant supports a year-long professional development program, culminating in a collaborative exhibit. They were one of five teams elected for the $15,000 grant for 2025.

“For me, the grant will help me educate myself—I never studied ceramics formally at an art school, beyond a little bit in high school—so much is a mystery. I don’t know why everything works, I only know what works. I want to keep growing, with all I’ve learned at the studio working with Steve.”

For the first half of the year, Ferenczy’s focus will be on furthering her understanding of the chemistry of clay. “In addition to working in the studio, I’ll be taking an online course in clay bodies. I’ll make my own clay recipe, for throwing large-section works. We already work with a good sculptural clay, but this will be my custom clay that Steve will continue to use, too, moving forward. I’ll also create a few custom glazes.”

The second half of the year will be about production, and toward the end of the year, Ferenczy will curate and produce a public exhibition, with a new body of her own large-scale works, alongside Procter’s. This will be Ferenczy’s first public exhibition.

— Paige Farrell