10 Emerging New England Artists

A New Panel of Nine Elevates the Voices and Visions of an Exceptional 10

Emerging is a versatile term. Art New England has enjoyed broadening its definition over the years since the inception of the Emerging Artists Issue. There are no boundaries in art, how could there be a set definition of an emerging artist?

Last year’s Emerging Artist Issue, amidst the height of the pandemic, was particularly poignant. Artists were intense, intentional, political, fired up. 2022 is no different. The personal and professional awakenings that have occurred as a result of pandemic-induced life changes have fostered bold ideas, deep conversations and powerful art. This year, however, we’re emerging from the pandemic itself. Injured, outraged, exhausted—and empowered. We’re wiser, grateful, more self-aware. What’s striking amongst all 10 emerging artists is their fearlessness. The journey of the past two years has not been lost on them.

There’s an energy in this moment that these artists have embraced. It’s found in the serenity and elegance of Berta Burr’s clouds and folded linens; the observant landscapes of musician-turned-painter Jarid del Deo; the choreography and community initiatives of Assi Coulibaly; the piercing poetry of Joan Kwon Glass; the healing themes within the work of Ryan Murray; Oona Gardner’s study of space and object through sculpture; the symbolic sculptures of William Ransom; Tyler Berry’s exquisite pursuit of the Old Masters; the expanding color palette of Lucy Mink’s oils and watercolors; and the fascinating projects of climate activist and interdisciplinary artist Justin Levesque.

These artists are working with new materials, wild ideas and a wide eye. They’re from small towns and big cities. They are of all ages. They’re problem solvers, soul soothers and explorers. They have much to say and are all in varying stages of emerging or re-emergence. We’re grateful for their stories, their honesty and a peek at their process.

One of the best aspects of this feature is the exuberance with which each artist is nominated. Working with the nominators is almost as much fun as working with the artists. Thanks and appreciation go to Jordan Sokol and Amaya Gurpide, co-artistic directors of Lyme Academy; Gerald Auten, senior lecturer in studio art and director, studio art exhibition program at Dartmouth College; Hilary Irons, gallery and exhibitions director at the University of New England; Sophie Bréchu-West, director and founder of 571 Projects in Stowe, VT; artist printmaker Edwige Charlot; Matt Garza, co-founder and creative director of Rhode Island’s The Haus of Glitter Dance Company; Rosemary Tracy Woods, executive director and chief curator of Art for the Soul Gallery; and Zoe Donald, managing editor, Diode Editions.

Ryan Murray

Springfield, MA

“When I first met Ryan Murray at an art showing at the Springfield City Library, I was moved by his shyness. He brings a quiet kindness and peace into every space he enters. I am filled with warmth when I think of his gentle nature given where he grew up, and he impresses me more every time I see him. I adore how open he is talking about mental health. His art feels like a desperately needed hug for the parts of us we have been told to keep in the dark, and there is so much power in that. It’s not a matter of if but when a contemporary art museum picks up his work,” says Rosemary Tracy Woods, executive director and chief curator of Art for the Soul Gallery

Ryan Murray has spent the better part of the pandemic working on community art projects: a mural in Springfield, MA, as a memorial to its forgotten history as a pivotal stop on the Underground Railroad; another at Gardening the Community, a food justice organization battling food deserts. The artist included a quote from its director Liz O’Gilvie: “When you heal the soil, you heal yourself and you heal your neighbors.” A theme of healing runs through Murray’s work; his art centers on mental health and the conversations, or lack thereof, within the Black community. “African Americans are four times more likely to develop some sort of mental illness than their white counterparts and out of that group only 20% seek treatment.” The barriers, he realizes, include access to healthcare and discussing generational trauma.

Murray, who graduated with a BFA from Carnegie Mellon in 2014, creates largely autobiographical work. “I was very shy growing up so I’ve been letting my art speak for me for a while now.” Being vulnerable himself, he hopes to normalize the topic of mental wellness. Murray paints scenes both urban and bucolic, present day and past. From Concrete, 2019, is a scene with three young boys playing basketball with a Wellbutrin instead of a ball. SSRI’s (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) are often featured in the artist’s pieces. As part of the permanent collection on the elevator doors at the Springfield Public Library is Inhibitors, 2019, a piece that features a woman, possibly a dancer, releasing of a fistful of medication in a beautiful arc. In the original piece, Murray uses medication as a material.

Murray starts to plot a painting using Photoshop. In some, the background has a pattern sprayed through objects found at a thrift store. The artist uses a mix of acrylic, spray paint, and stencils while being deliberately heavy handed. “[My work] is a pastiche of symbolism and imagery, a mix of stuff I have drawn, pictures I have taken and online stock images.” He then hand cuts the layers. This laborious process allows Murray to spend more intimate time with the piece.

His work examine every day struggles like the threat of police violence and its effect on the psyche of a community. In Flying the Coop, the artist examines the school to prison pipeline. He uses the number ‘twenty-five’ embedded in a highway sign as a reference to the percentage of Black Americans seeking treatment. “I knew the road more than I knew myself,” Murray says of the constant moving he did as a kid.

Murray will continue to use his platform to address mental health issues while hoping to increase the rate at which Black Americans receive treatment. In Transition, he puts himself at the forefront of this cathartic piece. “It makes me feel as large as I deserve to be and less self-conscious.”

— Jennifer Mancuso

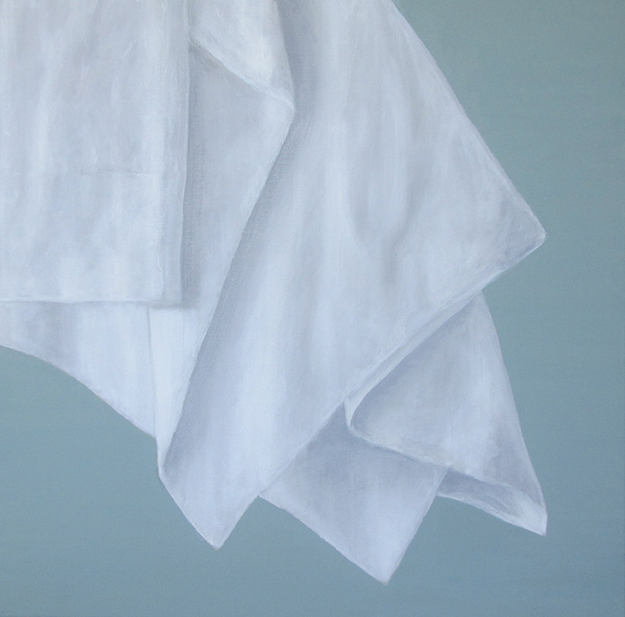

Berta Burr

Hoosick Falls, NY

“Viewing Berta Burr’s oil paintings on canvas—whether her sky scapes, or her draped fabric series—is a powerful and contemplative experience. The quality of her brushstrokes and the sheer, quiet beauty of her chosen palette compel us to linger. By focusing our attention on a detail of a landscape or still life, it’s as though she suggests the infinite possibilities of beauty and calm within the chaos of modern, everyday life.

Focusing her compositions on dispersing and coalescing clouds, Burr connects the viewer to the immensity of the wide open sky, and alludes at once to the sublime and the quotidian. Capturing the shifting beauty of cloud and sky, her paintings are profound, poetic and elemental: with great gentleness she offers the viewer a moment of wonder and a lens through which to rest the weary mind.

While her work is rooted in the history of art—the gorgeous, luminous skies of the painters of the Hudson River School come to mind, the stunning drapery folds of the Italian Renaissance—here she courageously offers a contemporary exploration of this subject matter, with altogether less artistic hubris and a great sense of her own deeply felt humanity,” says Sophie Bréchu-West, director and founder of 571 Projects in Stowe, VT.

“I have to admit that I’m merely post-adolescent. It’s been a long emergence.” That’s how Berta Burr describes her lifelong engagement with painting. Her career has been a mosaic of connecting with her artistic practice. Drawn to the performing arts yet discovering that tap dancing was not her calling, she swapped tap shoes for art lessons when she was younger. Her first contact with painting took place when she was four, “I discovered realism at that time. When I started working in a space of my own in 1980, I realized that it was where I wanted to be and what I wanted to be. I have never been bored when I was painting.”

“Boredom is a curse,” she states as she talks about her drive. And although she, like other artists, has faced moments of struggle, of concepts not translating well to the canvas, she shares, “Self-doubt is not a bad fuel.” And speaking to what is motivating Burr these days, her focus is towards common, everyday images that we may take for granted. Burr states that it’s important for her as an artist to “…awaken in people the possibility of beauty in things that are not unusual.”

Take something as simple as cloth and the way it folds or drapes. Upon Burr’s canvas these items carry a stillness and serenity. The viewer feels the folds, the creases, the softness of the fabric. “Recently, I have turned all my attention to painting draped cloth. There is a familiarity and a timelessness to [it].” Her technique is gentle and meticulous. Burr elaborates that her practice has been informed by working with her husband. “At a very young age, I married a harpsichord maker. He is a strict historicist and it has inspired my approach to researching techniques.”

Burr returned to the question of what it means to be an emerging artist, allowing some time for reflection after our interview. In answer, she shares: “I taped a quote by jazz artist Sonny Rollins to my wall; it is a studio motto of sorts. ‘I simply want to reach a level where I will never cease to make progress.’ Recognition as an emerging artist makes me think I am nearing that ideal. Also, another quote from Mark Twain, ‘I can live for two months on a good compliment.’ So it is with me, the compliment of being included in the Emerging Artist Issue of Art New England offers real sustenance.”

— Shanta Lee Gander

Jarid del Deo

Biddeford, ME

“Jarid’s paintings speak with the directness and intensity of a newcomer to a place of surprise and delight. His landscapes, often painted from direct observation, open up the beauty of a New England environment that often hides behind familiarity. Deeply anchored in both place and intentional defamiliarization, these works offer a window into a transcendent experience,” says Hilary Irons, gallery and exhibitions director at the University of New England.

It’s rather unconventional how Jarid del Deo found his way back to creating art after nearly 20 years of touring as a musician yet reinvention is at the core of his creative process. After graduating from University of New Hampshire with his BFA in the 90s, he separated from his visual arts background for a musician’s life.

At 40, del Deo decided abruptly to leave music for painting as he sat in the home of a fellow visual artist, feeling the saturation of his friend’s artistic vision as if “living in a painting.” This inspired del Deo—“something clicked and I told myself I was going to be a painter.” Just like that del Deo flew back to Maine, rented a studio and went to work, never to look back on his former life.

A decade later the modest del Deo is literal in describing his use of oil on canvas, paper or wood, yet his aesthetic is not. “I’m a landscape painter and the arrangement of color, shape and the mark making, that keeps me in a painting. I want people to relate to the landscape with signs of human activity. My subject matter is secondary to the more formal elements of painting and the human scale of a piece.”

What becomes noticeable is that del Deo’s process is undeniably present. There is a haunting realism and atypical nature to that which is recognizable. His paintings catch you off guard and comfort you in the same instant. Seldom does one see human subjects in his paintings however humanity runs throughout his work.

The struggle to find the best description for his art is precisely why Jarid del Deo succeeds. Every day he begins his narrative with a different take on the

subject matter and how he defines his work. Noting simply that he is an observer, “who is looking for that thing that catches his eye, the unique or strange. There is something aesthetically exciting about that.” This is how del Deo connects with his audience—through an undeniable eagerness to create.

— Maureen Canney

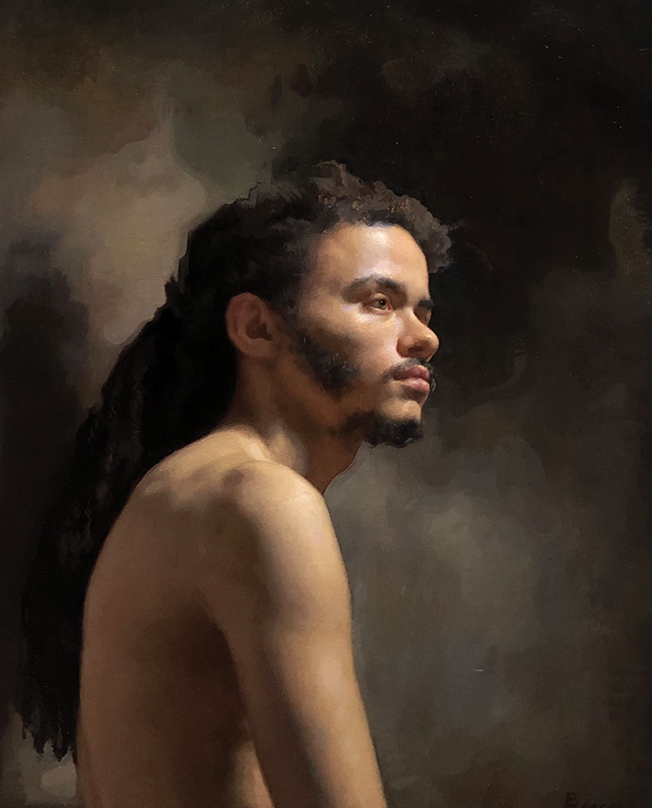

Tyler Berry

Long Island City, NY

“Tyler represents a rapidly growing number of young artists who have turned to an alternative form of art education, outside of the mainstream college or university setting, in search of a solid technical foundation in drawing and painting within the figurative tradition. Tyler’s work is exceptional in its virtuosity, and sensitive in its execution. He has an extremely bright future ahead of him, and we’re excited to watch his career develop,” say Jordan Sokol and Amaya Gurpide, co-artistic directors of Lyme Academy.

“I’ve been interested in learning how to draw and paint since I was a child,” says Middlefield, Connecticut-born artist Tyler Berry. He grew up playing piano and then skateboarding, two skill-based passions he believes fueled his interest to learn to draw. While earning a BFA at the Hartford Art School, he studied art history, illustration, and graphic design. The latter was a “career safety net” while illustration was an excuse to be in the model room for as many credits as he could fit into his schedule.

During his stint as an animator on the feature film Loving Vincent (2017), Berry had the opportunity to visit art museums across Europe. His encounters with the Old Masters sealed the deal: He set out to emulate their energy and spirit—and their accuracy.

To that end, Berry is currently wrapping up the final year of the Grand Central Atelier’s four-year core program, which offers artists “an authentic classical art education.” The fine-tuning his practice is undergoing is, he says, “just a necessary preamble” to fulfilling his artistic goal: to be in conversation with the Old Masters and develop “that common language.”

One of the headings on Berry’s website is “Academic,” an acknowledgment of his love for the tradition of precise rendering. He is especially

enamored of the nude figure, which he finds “infinitely beautiful, complex, and unique.” He doesn’t work from photographs, saying, “I just enjoy being present and working from life.”

Berry feels he is still in the “apprentice stage” of his career. His virtuoso studies of the human form say otherwise, providing ample evidence of an artist whose sense of line and contour simply amazes.

— Carl Little

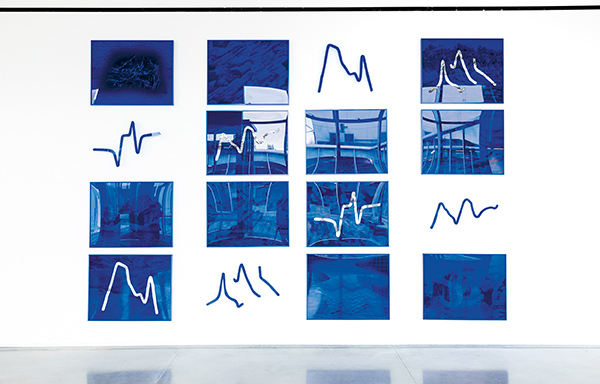

Justin Levesque

Portland, ME

“Justin Levesque is an incredible, innovative artist.In his photo-based practice, he has centered the unique relationship of the North Atlantic context to the Arctic. His interdisciplinary approach brings in historical narrative, environmental impact and attempts to locus the Queer and disabled body within that context. Justin has self-initiated artist-led partnerships and projects across disciplines and sectors and has yet to be fully recognized for his strategic leadership,” says artist printmaker Edwige Charlot.

Interdisciplinary artist Justin Levesque’s image-based, sculptural projects explore the interconnectivity between nature, cyberspace, history, and media culture. Using images of glaciers, ice, and other polar ecosystems, Levesque reconstructs the lens through which viewers experience the North Atlantic. Rather than stopping at the intersection of digital and material, Levesque’s works exist on a fluid continuum—the digital becomes material, creating a world within a world. Levesque creates a vehicle for these worlds to communicate through the color blue, a pigment synonymous with both nature and technology. Levesque’s monoprinting and UV printing techniques create dynamic, multi-layered compositions with blues of every shade: from deep navys and vivid ceruleans, to pale, icy hues and aquas with jewel undertones.

These projects are often part of larger conversations, like the ongoing climate crisis and the exploitation of the natural world as a means to gain popularity online. In 2019, Levesque’s Hoax, Heroic: Egocentric Magics Creepin’ On Your Socials in Blue (Frozen Networks) debuted as part of the Center for Maine Contemporary Art’s Melt Down exhibition. The three-dimensional, interactive installation used blue plexiglass, photo negatives, and laser-cut lines from scientific graphs to pose the question: How does the Arctic make you feel? Viewers were invited to call in and leave a voicemail response.

2022 proves to be an exciting year for Levesque, with new opportunities and projects on the horizon. “I’m always putting irons into fires,” he explains. “The hard work pays off by being strategic, persistent, and grateful.” Levesque is one of 30 artists chosen for the North Atlantic Triennial—a first-of-its-kind exhibition dedicated to contemporary art of the North Atlantic region. A historical collaboration between the Portland Museum of Art in Maine, the Reykjavík Art Museum in Iceland, and the Bildmuseet in Sweden, the triennial focuses on fostering the unique relationship between Maine and the Arctic countries. Once the exhibition closes on June 5 in Portland, Justin’s work will travel to the Reykjavík Art Museum where it will be on display through spring 2023. Born and raised in Maine, Levesque recognizes his love for artmaking in his home state. “I couldn’t have done this work anywhere

else,” he explains, “It has been super supported by the community.”

— Nicola Alexander

Lucy Mink

Contoocook, NH

“Lucy Mink lives and works in the studio in her home in Contoocook, New Hampshire. Her paintings are among some of the most original and intriguing works I’ve seen in quite some time. They vacillate between a mysterious abstraction, combinations of color and form that you’ve never seen, and a reassuring familiarity that you’re certain you can identify, that never settles. Her work is a door through which I travel to a place both wonderful and beguiling,” says Gerald Auten, senior lecturer in studio art and director, studio art exhibition program at Dartmouth College.

Lucy Mink is a patient artist, a characteristic that allows her to not worry if her paintings are not shown right away or when she needs to scrap a few pieces from the stretcher that aren’t working. It’s how she has built a successful art practice over the years with the idea of success evolving at different stages of her life. At one time, the artist felt accomplished with a studio in New York City, later winning the Pollock-Krasner grant, and was Dartmouth College’s artist-in-residence in 2018. Today, Mink, originally from New Jersey, paints from her home studio in New Hampshire, which allows her “to make things go in her favor a little bit.”

Mink’s impulse to paint started at a very young age and her primary goal was never rooted in money. “I didn’t know I wanted to go to art school until I knew it existed.” Without thinking of a career, Mink was drawn to Minneapolis College of Art and Design for grad school to immerse herself in painting and experience other artists. Her current practice toggles between paper and linen, watercolors, and oil paint, depending on what she can commit to on a given day.

Picky with the relationship of colors, the artist begins many of her pieces by mixing her own paint, an art in itself. Her small batches tend to be free from other mediums and use dry pigment. The benefit allows Mink to control the thickness and hue. This also sets the tone for the piece by establishing a color influence. “It’s almost as if you force yourself into using a limited palette because you are just using the colors you mixed.” After the color palette has been established, she saturates the linen using spray bottles and watercolors. This gives the painting an undercoat before starting with oil. Although the artist uses both linen and canvas, she prefers linen for the texture and because it’s less absorbent.

Mink keeps her better paintings in plain sight as a confidence boost. Despite her struggles in school, she received As in geometry and it’s understandable why. Her paintings often feature repeating patterns and symmetrical shapes. “The visual language of anything is no problem for me.”

Mink keeps the pressure off herself by not conforming to a particular color palette or theme. Her concern isn’t to keep the pieces cohesive as a series, yet she finds her work has a connectivity running through it. “I don’t really plan the work towards a show, I just keep making work.” It may take a little extra time to choose the pieces yet for that, Mink has an endless amount of patience.

— Jennifer Mancuso

Assi Coulibaly

Providence, RI

“Assi’s care-centered practice invites us to dismantle and strengthen our relationship with rest, and the ways we prioritize the physical body in our personal healing, relationships, and institutional advancement. Her work as a co-director of The Haus of Glitter, in lineage with The Yeredon Centre For The Malian Arts in Bamako, Mali (West Africa), is a powerful demonstration of the preservation of embodied Afro-diasporic tradition, history, culture, wisdom and evolution,” says Matt Garza, co-founder and creative director of Rhode Island’s The Haus of Glitter Dance Company.

Assi Coulibaly’s creative process doesn’t end once she leaves the studio—she lives it every day. The Rhode Island-based dancer and choreographer began training in traditional West African dance at age 13, honoring her Malian heritage. She also specializes in Latin, Dancehall, Step, and contemporary dance styles. Growing up between Mali and the U.S., Coulibaly dedicated her work to bridging the two cultures. “I make it a point to always serve as a representation of where I come from,” she explains. “Whether it’s wearing jewelry that has cowrie shells on it, or wearing clothing from Mali, it feels even more authentic to my artistic process.”

Community and legacy are at the heart of everything Coulibaly creates, and play a large role in her day-to-day work. She is one of the five founding members of The Haus of Glitter Dance Company, a Providence-based performing arts company dedicated to the creative liberation of queer and BIPOC artists. In September 2021, Coulibaly choreographed and performed in the company’s dance opera The Historical Fantasy of Esek Hopkins, remixing the history of the infamous slave ship owner and centering the stories of BIPOC individuals. Coulibaly uses each class as an opportunity to educate and inspire, especially when it comes to younger audiences. Her choreography is rooted in West African traditions, oftentimes with corresponding symbols or stories passed down from generation to generation. She is also the director of legacy, arts and education at Centre Yérédon in Bamako, Mali—a celebrated cultural center operated by her father, a master West African dancer.

The past two years have brought much introspection for Coulibaly, and “emerging” is the perfect term to describe the next chapter in her career. “I’m coming to a point where I’m reexamining myself and the intentions behind the work I’ll create for the rest of my life. So when I think about ‘emerging,’ I think about how I am the caterpillar in the cocoon. Now I’m ready to spread my wings, take flight, and continue this work.” This journey will begin with the 20th anniversary celebration of Centre Yérédon, where Coulibaly will bring other artists and colleagues from the U.S. to share in the culture. She’s also excited to continue her community engagement work with The Haus of Glitter, which is in the planning stages of its next project. Most of all, she is eager to continue creating her own legacy.

— Nicola Alexander

Oona Gardner

Norwich, VT

“Oona Gardner grew up in Vershire, Vermont and recently returned with her partner, artist William Ransom, and their family to live and work in Norwich, Vemont. Gardner is a ceramic artist whose practice includes drawing, photography and participatory installation. The conceptual rigor and meticulous attention to material detail she brings to her work places her amongst that group of artists who have recently expanded our appreciation of ceramics beyond the realms of function and craft,” says Gerald Auten, senior lecturer in studio art and director, studio art exhibition program at Dartmouth College.

When Oona Gardner thinks about her creative aesthetic there is a flow and action that emerge from her description. Gardner hopes that the viewer will experience her large scale, clay sculptures through a careful moving around her art as if in a dance. Not unlike her own creative process, where she too moves in an immersive motion of three-dimensionality through consistency, color and tactile-engagement.

Gardner grew up in Vermont, in quite a creative family: her father painted, her mother was a weaver, and her grandmother was a potter. Gardner was taught that art had a function and result and she found a clearer sense of her artistic vision while in the graduate program at Cranbrook Academy of Art in Bloomfield Hills, MI in 2006. It was there that she found inquiry.

“I did not have to answer everything in one piece and it did not have to fit into a prescribed result. The way objects and spaces impact us on a daily basis is incredibly important and often completely overlooked.”

Her experience in performance art has been a signifier in her long history of creating. “For sculpture to be understood one has to be able to move around it. That quality of the dimensionality, you have to use your memory, it’s somewhat durational. You have to walk and encounter it. As I have grown my practice, performance art has affected my aesthetic.”

In recent months, Gardner has expanded that sense of three-dimensionality, to a pre-semiotic aesthetic she acquired through the Feminist Art Collective in Los Angeles and philosopher Julia Kristeva prior to moving back to Vermont with her husband, and fellow Emerging Artist, William Ransom and their children.

“It’s this process of drive, as it exists before language is developed. Aesthetically it’s not connecting to any signifier. It’s more about touch and tactile engagement. The sense of the bodily. This has impacted me quite a bit.”

Gardner attests to a good deal of reflection happening over the past couple of years, moving towards smaller scale projects and reopening herself to more opportunities. What’s exciting is that the expanse of her inquiry is not limited to her art but also to her individual maturation, therein lies such possibility in her prodigious dance with clay.

— Maureen Canney

William Ransom

Norwich, VT

“William Ransom grew up on a farm in Strafford, Vermont and recently returned to Norwich Vermont with his partner, artist Oona Gardner, and family after living in Los Angeles for a decade. He is a sculptor who transforms the most ordinary material such as wood strips, clamps, ash, charred wood, and billboards into powerful critiques of the U.S. and its sociopolitical history. Ransom’s masterly combination of form and content deserve a closer look,” says Gerald Auten, senior lecturer in studio art and director, studio art exhibition program at Dartmouth College.

Shortly after William Ransom graduated with a MFA from California’s Claremont University, he had a moment of clarity that shaped his artistic career unilaterally. It was the addition of a simple clamp into his artwork that opened up “the possibility of a new, different type of abstraction that allowed my work to be more about that visceral encounter.”

Ransom grew up as a Black man on a Vermont dairy farm and was greatly influenced by his mother, an artist herself, and his uncle who was “an interesting and eclectic man who leaned heavily into his own self-expression without concern for what others thought.”

This fostered a sense of problem solving and improvisation that influenced Ransom’s engagement with his artistic materials. He is a sculptor who incorporates wood, vinyl, concrete, clamps, tar, drawing, graphite, color, spray paint and fire to elicit an emotional response, yet every addition to his sculpture has intention.

At the time of this article, Ransom had just submitted the second installment of a billboard to the Social Justice Billboard Project, created in response to the murder of George Floyd, and located just above George Floyd Square in Minneapolis, MN. Ransom’s first installment in 2020 won that year’s Gold Obie award. “That billboard, and the one I just sent, remains the only time that I have put something into the world that I haven’t laid eyes on. That stretched my self-definition as a sculptor.”

The relevance of his art and voice as a Black man in the world, can be seen in a piece that he created after finding his family’s last known relative in North Carolina in 1832, an enslaved man named Jupiter, who was valued at $500. In response, Ransom encased five one hundred dollar bills into cement being held by a clamp, “illustrating the theme of bondage, in an action that can never be undone.”

Ransom was shaken by the murder of George Floyd and the cultural reckoning of 2020, and stepped into the studio to find his response. He has always incorporated tension into his work in order to elicit an empathic, visceral reaction. In a time when it is most important to share one’s experiences, to act and speak boldly, Ransom through his art, is becoming a powerful, influential voice.

— Maureen Canney

Joan Kwon Glass

Milford, CT

“Joan Kwon Glass works in opposition to silence. Her writing dares us to hold ourselves in our grief—our pain—to keep ourselves here. Gone are the euphemisms, the etiquette, those barriers to feeling. Her poems are doors ‘swung wide open’ to the frigid cold. They are breathtaking. Glass is a torrential writer. The author of three works of poetry forthcoming in 2022, she serves as the Poet Laureate for the city of Milford, Connecticut,” says Zoe Donald, managing editor, Diode Editions.

Hello Kitty notebooks every summer while in Korea; asking her family for the typewriter she so wanted for Christmas. This is how Joan Kwon Glass first came to writing. Glass describes her first memory of pen to paper: “I know exactly when it was.

I was about five years old and I’d just learned how to write sentences. I was alone a lot as the oldest child.” Every summer, while spending time with her mother’s family in Korea, those Hello Kitty notebooks were her outlet. Writing remains that place where she turns to “try to figure out what I am feeling or trying to process certain situations.”

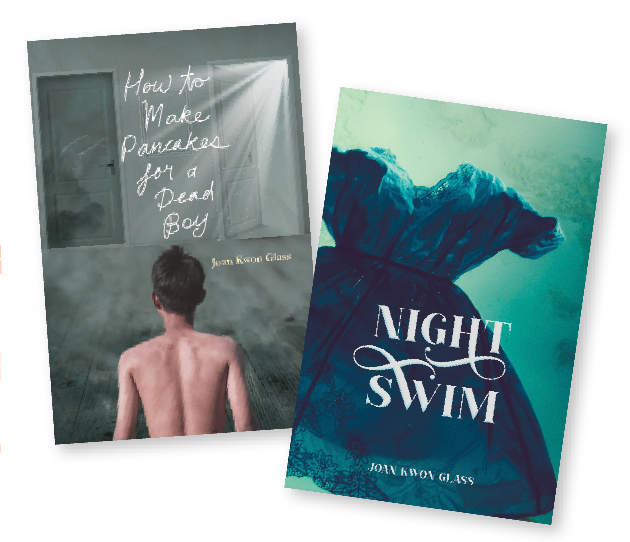

When it comes to the question of how Glass relates to the emerging artist description, the term is both challenged and reinforced by her successes over the past year which include Night Swim, her poetry debut and winner of the 2021 Diode Editions full-length book prize; How to Make Pancakes for a Dead Boy (Harbor Editions, 2022), and If Rust Can Grow on the Moon (Milk & Cake Press, 2022). Glass shares honestly, “I don’t know the answer to that question. It’s been amazing, surreal and it’s been strange because everything happened so quickly. I felt like I was an emerging writer for a very long time and I still consider myself to be emerging but I don’t know that other people would. I feel like I am always going to be emerging.”

Given this growing body of work from Glass’s period of emerging, it is impossible not to explore the connective tissue, the themes existing between the chapbooks (a publication of up to 40 pages, often poetry bound by saddle stitch), the micro-chapbook (approximately 10 pages), and her full-length work. How to Make Pancakes for a Dead Boy focuses on the loss of Glass’s 11-year old nephew to suicide in 2017; it’s the navigation of grief in the midst of trying to continue to parent her own children. Night Swim offers a deeper dive with the inclusion of poems from her chapbook in addition to grappling with the loss of her sister under similar circumstances. Organized around the five stages of grief, both books offer different angles, nuances on one individual’s cartography of loss and surviving. They are delicate and devastating.

As her work continues to unfurl in the world, we look forward to Glass sharing, through verse, more of her journey through the human experience.

— Shanta Lee Gander