- Fiore at 100: Maine Observed

Maine Art Gallery, Wiscasset, ME • maineartgallerywiscasset.org • Through August 24, 2025

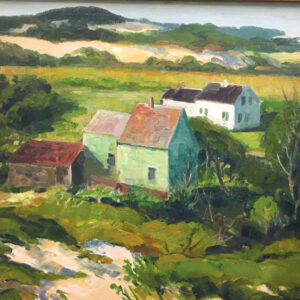

Joseph Fiore, Megunticook, 1987, oil on canvas, 38 x 48″. Courtesy Maine Farmland Trust and Maine Art Gallery. While at Black Mountain College in the 1950s, as student and then teacher, painter Joseph Fiore (1925–2008) worked with, and alongside, the likes of Josef Albers, Willem De Kooning and Ilya Bolotowsky. As art scholar Mary Emma Harris has noted, there was an expectation at the college to be abstract, a directive Fiore respected but also rebelled against over a creative lifetime.

Curated by watercolorist David Dewey, a former Fiore student, this exhibition highlights the painter’s transition from abstraction to representation—and back again, often overlapping. Arriving in Maine with his family in 1959, the painter shifted to a realist mode. As it has for so many artists before and after him, the landscape cast an irresistible spell.

Fiore wasted little time responding to the tidal reaches and rock-bound edge of the Gulf of Maine, setting up his easel in front of various coastal prospects. He also looked inland, to orchards, hay fields and a view of distant Mount Katahdin. As art historian Susan Danly observed in the monograph Nature Observed: The Landscapes of Joseph Fiore, “The big theatre of nature rather than the indoor drama of the art world held Fiore’s attention and affection.”

Later in life, Fiore embraced his earlier abstract leanings. “Conflating time, observation, and memory,” states arts writer Suzette McAvoy in the exhibition catalogue, “these late works, like the sonorous Sounds of the Mountain, 1985, and Megunticook, 1987, reflect on the symbiotic relationship between the earth and humankind.” The latter painting offers four landscapes in one, riffing on the mid-coast Maine lake and mountain in different seasons.

“It is like a journey laid out in visual shorthand,” Danly has written.Fiore was an active member of the nonprofit Maine Art Gallery in the 1960s and ‘70s. In celebration of the hundredth year of his birth, the gallery is partnering with Maine Farmland Trust, which was gifted a significant portion of his estate in honor of its work to preserve Maine farms. Fiore at 100: Maine Observed is an overdue—and most welcome—survey, making a powerful case for revisiting and admiring anew this artist’s remarkable work.

— Carl Little

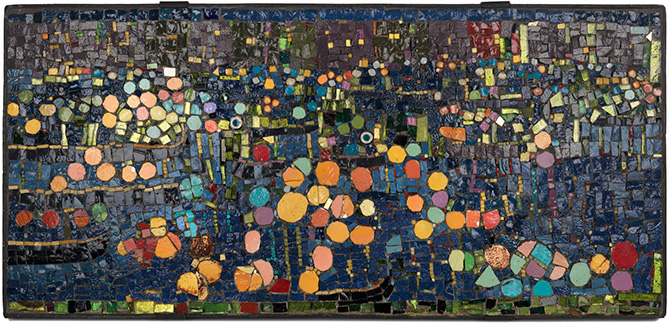

- MosaicArt Collective

Mosaic Art Collective, Manchester, NH • mosaicartcollective.com • Through June 27, 2025

Donna Catanzaro, Relationships, mixed media, 3 x 12 x 6″. Courtesy of the artist. Liz Pieroni moved back to southern New Hampshire during the pandemic. As she struggled to find studio space and a gallery that suited her needs, she realized others must be having the same problem. Pieroni began to reach out to fellow artists and makers in the community, and in 2022, Mosaic Art Collective was founded.

Mosaic consists of studio spaces for four artists and one gallerist, Amy Regan. Regan runs her boutique gallery See Saw Art out of the Collective. Mosaic runs their own storefront gallery space where they show monthly exhibitions around centralized themes. Most of these shows are open call. “I’d say the majority of the experience is based on building community around art,” said Pieroni. “There’s a lot of people that need to be in and around communities that make art.”

On view this spring, Impressions is themed around the concept of printmaking. The Collective’s first genre show, this exhibition seeks to expand the boundaries of what we call printmaking. Traditional methods such as lithograph, monoprint and screen printing will be on display as well as non-traditional methods including photography and 3D printed art as a form of sculptural printmaking. There will be an opening reception for this show on May 10. “You can expect lots of people that are wanting to talk to you, wanting to learn more about what you’re making, your process, it’s just a really great way of meeting new people.”

Community building is at the center of what the Mosaic Art Collective does. And never has this been more important. With federal funding cuts affecting the New Hampshire State Council on the Arts, many artists in the region will be feeling the loss of grants and support. “As culture keepers and history record keepers, which is what all artists are, I think it’s really important for our society to have this understanding of how important it is to show up for these events and show up for your friends who make art, even if it’s their first show or it’s their 70th show, to show up at these openings and take a chance and find local art galleries.”

— Autumn Duke

- Nora Valdez: ESPERANDO/WAITING

Boston Sculptors Gallery, Boston, MA • bostonsculptors.com • Through June 8, 2025

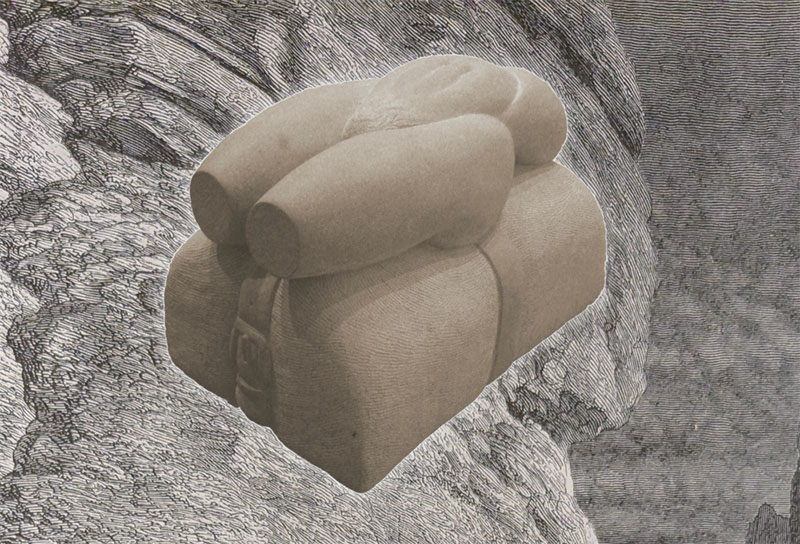

Package, Indiana Limestone , 36 x 21 x 20″. Courtesy of the artist. ESPERANDO/WAITING, Nora Valdez’ exhibition at Boston Sculptors Gallery leads the viewer on a journey that seems endless. The artist writes, “I realize I feel I’m always waiting . . . but for what? What exactly is it that I’m waiting for?” Originally from Argentina, Valdez has always felt suspended between two worlds.

Package, a particularly powerful installation, is an 8 x 10 foot drawing on two corners of a wall with a limestone sculpture of a woman’s torso atop a belted bundle. The torso is a metaphor for the artist’s self that she carries from place to place. The surrounding over life-sized drawings in black pastel pencil on the corner walls are figures in waiting—unwitting witnesses to the passage of Package—as anonymous as immigrants who can never be sure how they will be treated. A grey granite column to the right with a drawing of a face entitled My mother’s words includes words in Spanish, “Te espere y nunca regresaste.” “I wait for you, and you never come.”

On an opposite wall is a grid of ten ink drawings set in white hand-carved wood frames from Cuzco, Peru. The series, Esperando/Waiting, is drawn directly onto pages of an old book of Gustave Dore etchings. There is a powerful dialogue between the journeying figures and the delicately etched scenes, as if alluding to the continuity of the human journey yet not bound by time.

In addition to the installation and drawings, there are several limestone carvings of figures huddled together as if seeking protection, and a circle of child-sized white chairs with hands holding each other. Another wall shows photographs of Valdez’ numerous public art sculptures.

This sense of “waiting” is something that is shared amongst many people today. Valdez’s ability to infuse these drawings and sculptures with a sense of life passage is uncanny. Such work can only emanate from deeply held questions. This is a rare, emotionally full exhibition, one that gives voice to the questions that many of us live with daily. Perhaps there is comfort in seeing a reflection of shared feelings expressed in a most sensitive manner.

—B. Amore

- Michael Beatty: Fabrications

Iris and B. Gerald Cantor Art Gallery, College of the Holy Cross, Worcester, MA • holycross.edu • Through April 1, 2025

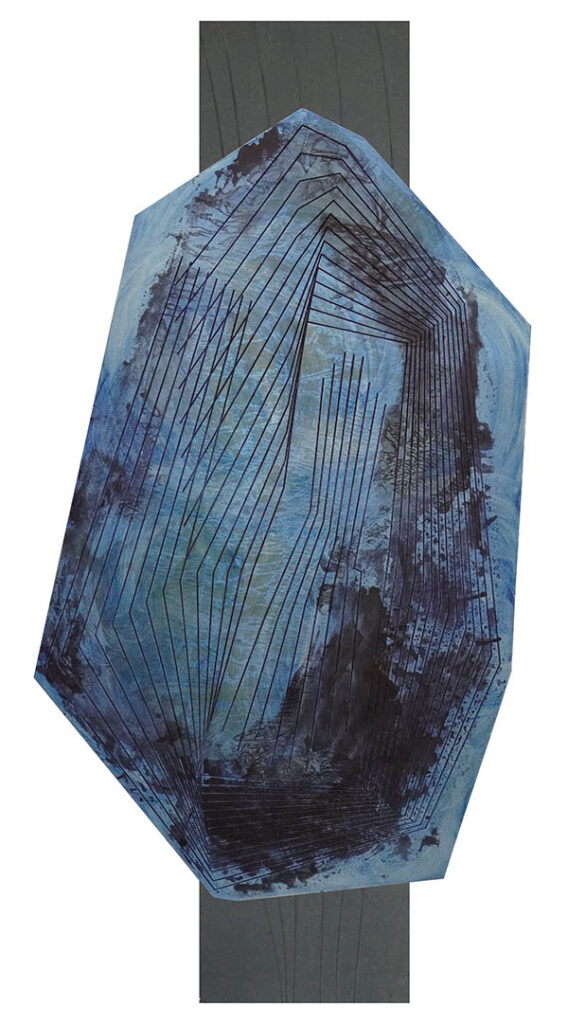

Michael Beatty, Core #6, 2011, birch plywood with milk paint and wax, 13¼ x 10 x 5¾”. Courtesy of the artist. Professor Emeritus Michael Beatty considers himself “a maker of objects.” Thus, Fabrications is just the right name for this exhibition, which combines his “sculptures” alongside drawings, prints, and study models. The engaging display spotlights Beatty’s playfully philosophical output, from 1992 to the present.

In the Visual Arts Department at Holy Cross, Beatty taught sculpture and 3-D design for twenty-five years, before retiring in 2023. His works are an amalgam of techniques and materials, influences and themes. For Beatty, an interdisciplinary crafts maker, process is key. He’ll start with a doodle or a sketch, use technology-assisted methods to visualize his ideas, and give them shape using wood, steel, and 3-D printing.

Beatty considers his work “drawings in space.” In Twist/Hold, a narrow ribbon of bent laminated wood supported by skinny steel “girders” looks like a minimalist roller coaster. It’s graceful and soothing. In a trio of drawings, Beatty connects a strong geometric line with a curvilinear shape, thus uniting rigid and flowing forms. Beatty gives this approach a second life—in 3D—with two small sculptures of welded steel and laminated wood.

Three small objects from Beatty’s birch plywood “Core” series, which is inspired by CT scans, resemble botanical shapes, and thus link body and nature. In Plato’s Chalkboard, a series of monotypes produced in collaboration with printmaker James Stroud of Center Street Studio, Beatty calls forth floating, wire-like objects that visualize the theories about three-dimensional shapes that Plato posited—without illustrations.

Another series, “Blips,” is comprised of small, lathe-turned bulbous objects covered in graphite. Inspired by cosmic images from the Hubble telescope, these playful extensions of Beatty’s fundamental forms are arrayed in out-of-the-way spaces throughout the show.

A special highlight of the exhibition, a mock-up of Beatty’s studio, unveils his iterative and experimental process of making. It’s filled with sketches, maquettes, prototypes, and works in progress—all in conversation with each other.

The fabrications dreamed up by Beatty invoke feelings of wonder. “Beatty’s abstract works,” says gallery director Lauren Szumita, “are inspired by very real things—in nature, architecture, space, and the human form. There are traces of something familiar that are just out of reach. Beatty wants us to be comfortable with not finding out the answers, but to think about our experience.”

— Jack Curtis

- Four Related Visions: David M. Carroll, Laurette Carroll,Sean Carroll, Riana Frost

Two Villages Art Society, Hopkinton, NH • twovillagesart.org • Through April 19, 2025

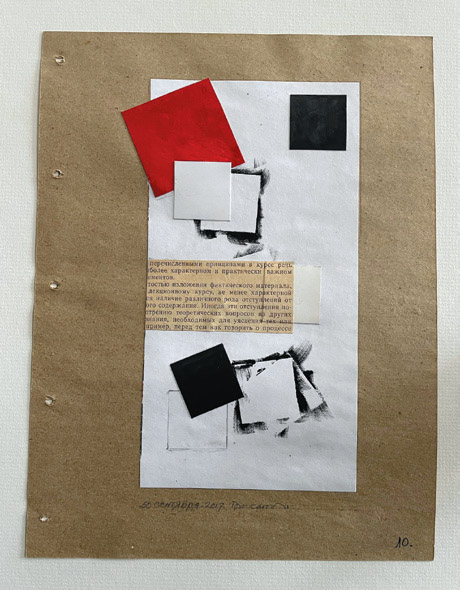

David M. Carroll, Russian Avant Garde inspired work, Untitled. Photo: Laurie D. Morrissey. It is rare for an artist well-known for a distinctive kind of work and subject matter to make a major artistic shift late in his career. David M. Carroll, a MacArthur “genius grant” recipient, artist, illustrator, and author, recently moved into Cubist-influenced art and surrealism. His latest work is abstract, non-objective art inspired by the Russian Avant-Garde movement. The current exhibition at Two Villages Art Society features some of this new work as well as the natural history paintings for which he is known. The latter work will be familiar to readers of Carroll’s acclaimed books on the wildlife of the wetlands (including The Year of the Turtle, Trout Reflections, and Swampwalker’s Journal).

In Four Related Visions, Carroll’s work is displayed alongside that of family members. The exhibition is grounded in their family bond and the natural surroundings of their home in rural New Hampshire. The woods, wetlands, and semi-wild gardens surrounding their 250-year-old home figure in the work of these lifelong artists.

David M. Carroll’s wife, Laurette Carroll, paints in oils, acrylics, watercolor and paste, often using mixed media and integrating drawing and collage elements into her paintings. Her approaches range from naturalistic to impressionistic and abstract. She paints mainly from nature and often incorporates writing from her garden journals into her paintings of flowers and garden landscapes. The couple’s son, Sean, who makes his living restoring old houses, is a plein air painter focusing on landscapes and fishing scenes in Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine. Daughter Riana Frost paints moose, deer, and other animals on wild turkey feathers she obtains from licensed hunters. She paints in acrylic with a very fine brush on the challenging surface of the feather.

In addition to original paintings, drawings, sculptures, and painted clay vessels, the gallery will have prints and books for sale. There will also be an opening reception with the artists March 22 from 12-2 p.m.

Two Villages Art Society’s gallery is a small brick building on the main street of Contoocook, a village in the town of Hopkinton, and is in walking distance to a river, historic covered bridge, small shops, and restaurants.

— Laurie D. Morrissey

- From Haiti to Vermont

South Burlington Library, Burlington, VT • southburlingtonlibrary.org • Through April 2025

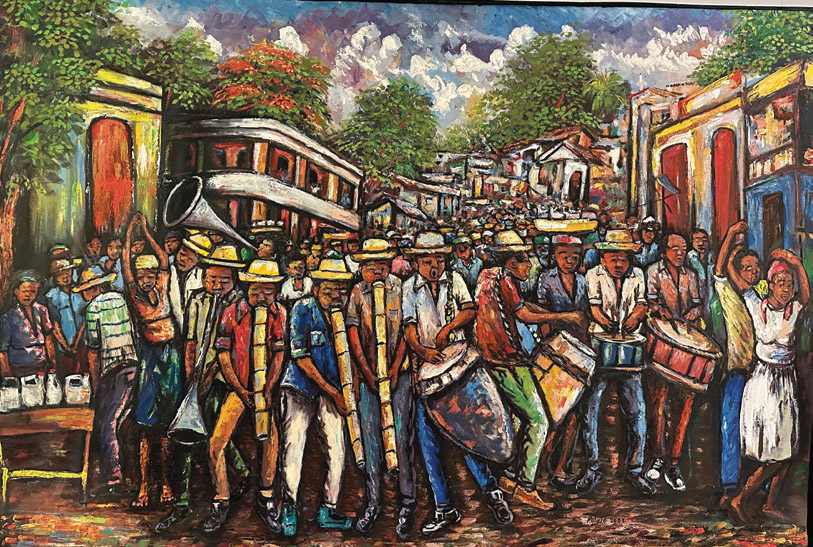

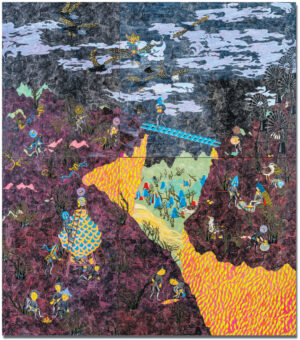

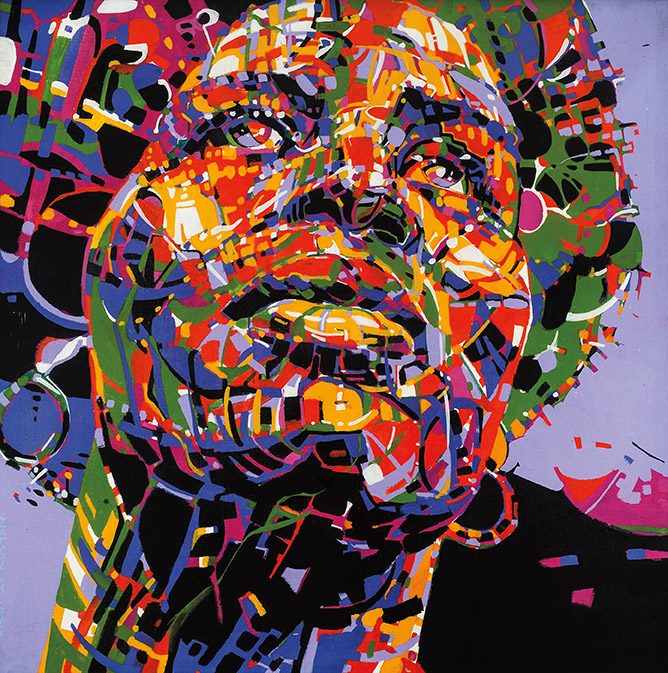

The Village Band, 2022, acrylic on canvas, 71 x 61″. Courtesy of the artist. Most artists are motivated by an inner drive to create but few are as productive as Vermont artist Pievy Polyte. Starting in December 2024 and extending through the end of April 2025, Polyte’s colorful, often joyful paintings of his Haitian homeland’s lush landscape and hard-working people are on view in three separate but overlapping exhibitions.

Polyte is a natural born collaborator, and his exhibitions are in venues supported by local businesses and organizations. A month after he installed his eyepopping paintings on the walls of the popular, renovated, Maltex mill building turned office complex in Burlington’s trendy South End Arts District, he was hanging a selection of figurative and landscape paintings at The Skinny Pancake, a Burlington waterfront restaurant, and in February the South Burlington Library hosted From Haiti to Vermont, its second solo exhibition of the prolific painter’s work. His first exhibition at the library in 2024 garnered so much positive attention that the University of Vermont acquired two large scale paintings from this show. Stylistically, Polyte employs the flattening of forms and compressed perspective of folk art, yet he injects a more sophisticated acknowledgement of cubism’s influence in his compositions. His landscapes recall French post-impressionist Henri Rousseau (1844–1910) in their reduction of natural forms to a system of patterns that dance across the surface adding rhythm and detail.

More than an artist, Polyte is a modern Renaissance man. He is an agronomist, educator, and accomplished chef. Growing-up on a Haitian coffee farm prepared him to become the founder of a coffee cooperative called Peak Macaya, which is a beneficiary of profits from his art sales. He is also planning on forming a U.S.-based non-profit to sell Peak Macaya coffee which may also include a brick and mortar café which presumably would have wall space for future artwork. Deeply inspired by the natural world, Polyte recognizes the importance of engaging Haiti’s children to appreciate the land. To this end, he supports two schools in Haiti that emphasize environmental education. At the opening of his first solo show at the South Burlington Library visitors were treated to an elaborate buffet of Haitian specialty dishes, all prepared by the artist, making this exhibition a treat for the stomach as well as the eyes.

— Cynthia Close

- Blanche Lazzell: Becoming an American Modernist

Changing Art Gallery, Bruce Museum, Greenwich, CT • brucemuseum.org • Through April 27, 2025

Planes II, block cut 1952, printed 1952, color woodblock print, 19⅛ x 21⅛ x 1½ (framed). Art Museum of West Virginia University Collection, gift of Harvey D. Peyton. 2004.1. Fauvism, Cubism and Abstract Expressionism all factored into Blanche Lazzell’s masterful white line woodcuts and paintings. Bruce Museum visitors are offered a rare glimpse at the work of this 20th century artist. At a time when only women of means had access to art training and even fewer had the chance to establish working studios and professional careers, Lazzell was a standout. This is the first monographic exhibition of her work in nearly two decades.

Lazzell had an extensive arts education, earning an undergraduate degree in fine art at West Virginia University, furthering her studies in New York, Paris, and Provincetown, MA. She took classes alongside Georgia O’Keeffe at the Art Students League in New York, and worked with Cubists Fernand Léger, André Lhote, and Albert Gleizes in Paris while a student at Académie Julian and Académie Moderne. She studied with Abstract Expressionist painter Hans Hofmann after putting down roots in Provincetown, MA. It was during her years in Provincetown, where she taught and maintained a studio, that she became known as a master of white line woodcuts. Her bright hues, simplified forms, and a flat Japanese aesthetic was an amalgam of influences that she distilled into a uniquely American–and highly personal—art form.

Women of talent and means flocked to Paris in the early part of the 20th century for the freedom it offered. Afterwards when Lazzell set up in Provincetown, she did not have a key patron, as O’Keeffe had in Alfred Stieglitz. Her smallish prints —which were easy to frame, wrap, and ship for inclusion in exhibitions—were at times perhaps dismissed as of lesser quality to painting. And, there was the matter of her family’s decision to donate her works after her death in 1956 to the West Virginia University Art Museum, in effect removing her art from major markets. The exhibition, featuring more than sixty paintings, prints, and unique works on paper, acts as a curative.

Bruce Museum curator Jordan Hillman singles out Lazzell’s Provincetown Church series that moves from charcoal preparatory drawing to woodblock to white-line print, and finally to oil painting. It was undertaken the year before her second trip to Paris, and offers “a unique glimpse into Lazzell’s creative process but also anticipates the increasingly abstract and flattened quality of her later work,” she said.

The Bruce’s presentation is unique—it’s organized chronologically, has new didactic materials, works from the Museum and local collectors, and incorporates an in-gallery interactive space. The exhibition will travel to the Albany Institute of History and Art and then to the Provincetown Art Association.

— Kristin Nord

- The Art Center

The Art Center, Dover, NH • theartcenterdover.com • Ongoing

Installation view of the Contemporary Abstract exhibition. Courtesy of the gallery. The Art Center, nestled in a mill building at the heart of downtown Dover, is filled to bursting with art, artists and artmaking. The most recent exhibition, Annual Contemporary Abstract Exhibition, took up most of the space in the gallery with abstract contemporary art from national and international artists. This year’s exhibition was dedicated to Tim Gilbert, an Art Center member artist who sadly passed away in October 2024. In the back of the gallery, a smaller exhibition, The Abstract 4: Abstracting Winter in New England, featured themed work by regional New England artists. Sequestered in a partially enclosed corner is the ongoing Small Works show, with pieces available for purchase in a varied mediums from painting to woodworking to sculpture.

The Art Center is an open-concept space offering visitors clear views of working artists in their studios. Artists can be seen coming and going from their work, sharing ideas and greetings with each other and with owner Rebecca Proctor. The mixed-use Washington Mills building invites collaboration between local artists and businesses, of which The Art Center is a part.

In addition to its being a gallery space, The Art Center also provides studio spaces for working artists ranging from private rooms to open cubicle-style arrangements. The Art Center hosts two artist residencies on-site, one for printmaking, the other for painting. For both residencies, each artist has four months to create a body of work to be shown in a group show at The Art Center the following year. The Center puts three artists through each program annually. The printmaking studio, complete with two different printing presses and a variety of other materials, is also available to rent for three-to-four-hour sessions. Proctor runs a custom framing business out the space as well.

The gallery is going through changes in the coming months as Proctor works to move some of the studio space and materials to a newly purchased third-floor suite in the same building. The new space will include pottery, the existing printmaking studio and more. “People can look in and they’re going to see people doing pottery and printmaking in an open setting,” said Proctor of her plans.

— Autumn Duke

- AS220

AS220, Providence, RI • as220.org • Ongoing

AS220 Youth perform at annual FutureWorlds afrofuturist hip hop production. Photo: David Lawlor. AS220 is a non-profit community arts organization founded in Providence, Rhode Island in 1985 as an inclusive space for artists—a place where artists could freely experiment and explore their interests without the constraints imposed by art institutions, commercial galleries, and critics. Since its inception, it has been a cornerstone of Providence’s vibrant arts scene and remains committed to its mission of making the arts accessible to all.

AS220 offers numerous opportunities for artists and performers to showcase their work to the public. The organization hosts an array of exhibitions, concerts, and performances throughout the year across its many galleries and stages. AS220 also offers access to community studios and workspaces for practicing artists, including painting studios, print shops, a darkroom, media arts facilities, a recording studio, and spaces for dance, theater, and improv. Numerous workshops and classes are available to the public for those looking to learn new creative skills.

The organization also empowers young Rhode Islanders through AS220 Youth, which offers after-school arts programs. Drawing inspiration from hip-hop, Afrofuturism, and social justice, the program provides multimedia arts instruction in visual, media, and performing arts, giving young people the tools to express themselves and engage with critical social issues.

A major component of AS220’s commitment to fostering the arts is its resident artist program. The organization provides affordable live-work apartments to approximately 65 artists across three mixed-use buildings in downtown Providence, the majority of which are government-designated affordable housing units. Residents also have convenient access to AS220’s studios and art-making facilities, as well as exclusive opportunities to exhibit their work or present performances to the public.

Artists of all disciplines and backgrounds are welcome to apply for residency in these live-work units. Since many of these apartments are designated affordable housing units, applicants must be below a maximum income threshold to qualify. The application process includes submitting an artistic biography, resume, and work samples. Shortlisted candidates are invited to interview with a panel of AS220 residents and staff. For more details, including information on current opportunities, visit as220.org/live-work-studios or email live-work@as220.org to be added to the vacancy notification list.

— Michael W. Zhang

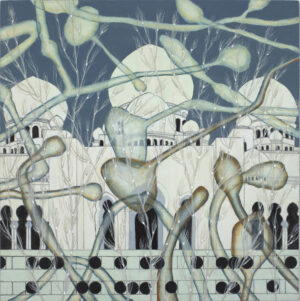

- Kate Hargrave: The Journal

Elizabeth Moss Galleries, Portland, ME • elizabethmossgalleries.com • January 10–March 8, 2025

Kate Hargrave, The Fisherman’s Shadow, 2023, oil on birch panel, 30 x 40″. Courtesy of Moss Galleries. In a statement about her work on her website, Maine-based artist Kate Hargrave traces the subjects of her complex and intriguing paintings to a range of sources, from art history and children’s books to “early peer relationships, parenting and caregiving.” All of those sources are in evidence, often in a brilliant fusion, in the nine, largish oil-on-birch-panel paintings that comprise Hargrave’s first solo show.

Take The Orchard Road: the sheer number of mainly pubescent female figures—dressed, half-dressed, naked—involved in all manner of activities on a dark tree-lined thoroughfare might bring to mind Hieronymus Bosch. Hargrave creates her own garden of earthly delights yet filtered through the consciousness of a teenage girl. “With a willingness to indulge my own sensibilities,” Hargrave has explained, “I explore where memory and the subconscious reveal an adolescent realm in my work.” This statement ties her to Surrealism which, art historian Mary Ann Caws wrote recently in The Brooklyn Rail, “guarantees the constant exchange and thought that must exist between the exterior and interior worlds.”

Paintings like The Milkman’s Arrival, The Babysitter and The Penpal hark back to the dream-like scenarios in certain Leonora Carrington canvases. Hargrave is more of a storyteller: each canvas, in title and imagery, prompts diverse storylines of, in Hargrave’s words, “vulnerability and self-determination.” As your eye takes in the vignettes that unfold in humble fairytale interiors, you’re invited to wonder who the milkman, babysitter and penpal are and what their roles might be in this parallel world.

In The Fisherman’s Shadow a number of spectral apparitions interact with the figures, their wraith-like forms floating, grasping, hovering. Again, as one engages with the details in what Hargrave calls this “ambiguous territory,” one is tempted to uncover the mystery of this strange tableau, to start a “once upon a time” tale.

A 2003 graduate of the Rhode Island School of Design, Hargrave is starting to appear on the radars of art aficionados in Maine and beyond. It’s no surprise: the paintings are remarkable in their sophistication and vision. This is a debut to remember.

— Carl Little

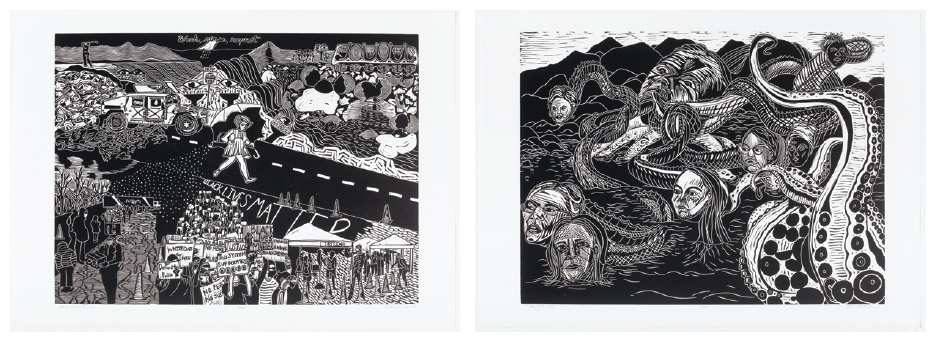

- AEROSOL: Boston’s Graffiti DNA, its Origin & Evolution

ShowUp Gallery, Boston, MA • showupinc.org • Through February 16, 2025

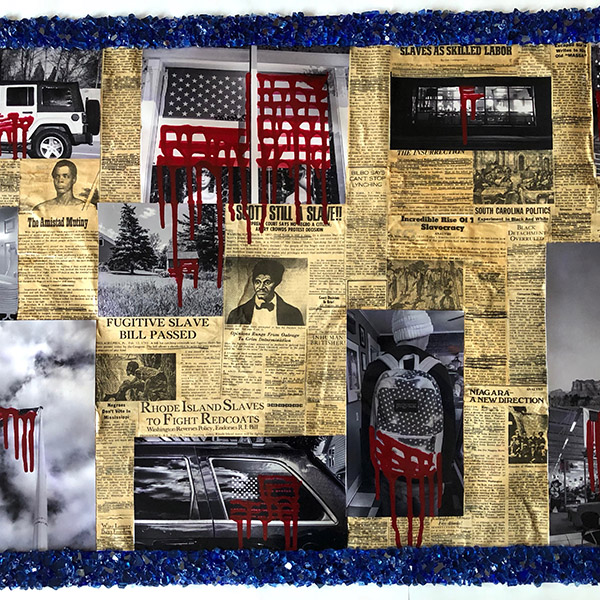

Visitors view works by David “DS7” Taylor (left), Rob Stull (top), and Chepe “Sane” Leña (bottom). Photo: Aron Lee. There’s nothing more sacred than when a group of artists find their kindred and commit to their craft boldly and unapologetically. In a time when the history of people of color is under the gun of censorship, it’s the artists who dig their heels even deeper to sustain their presence. Walking into the gallery, one is met with the immediate presence of energy, history, and artistry. Whether it’s Shea Justice’s parchment display of the shadows of collage art whose images travel back to Jim Crow legacies fiercely contested by Fannie Lou Hamer and James Baldwin. Or Timmy “Zone” Allen’s imagery of the historical racialized violence of policing alongside the monochromatic figures of Langston Hughes, W.E.B. Dubois, and a lone figure of Harriet Tubman next to an Indigenous child noting the cultural intersections of colonialism. Or the nod to a futurist and colorful burst of nonbinary Black faces in a digital simulation by Barrington “Vex” Edwards. As a viewer, the thematic range of this aerosol art reads more like a cultural document that should reside back in the open spaces of Boston as a permanent historical archive, not the transient spaces of art galleries.

A short documentary by filmmaker Paris Angelo airs on a continuous feed in a makeshift theater whose walls cocoon the viewer in a dark landscape mimicing the vibrant art that was once birthed under a night sky. In a poignant moment in the film, Chepe “Sane” Leña confirms the artistry not as random, stressing that one had to be a part of the culture, and not simply possess the ability of can control. The culture that these artists created is similar to that of historical-diasporic Maroon culture, a practice that Dr. Tiffany D. Pogue states where people of color “liberated themselves in a space in which they could be absolutely sovereign and express themselves culturally.”

A dated newspaper article headlines Peters Park Street Artists Decry the Loss of Their Wall. Next to that headline is a photograph of ten writers standing together, unwavering, poised as a clan whose individual stances/body language translates as a knowing that the world is their wall. It is their presence on the walls of this gallery that amplifies a lineage of storytellers whose voices are unwavering, their art enduring.

Curated by Jennifer Mancuso, the exhibition also features artists Ricardo “Deme 5” Gomez, Rob Stull, and David “DS7” Taylor.

— Asata Radcliffe

- Franklin Williams: It’s about Love

David Winton Bell Gallery (The Bell) at Brown University, Providence, RI • bell.brown.edu • Through December 8, 2024

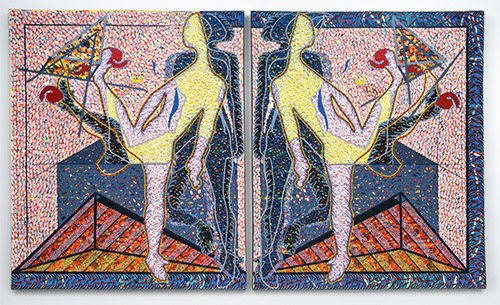

Franklin Williams, Twins (Pt. 1 & 2), 1976, acrylic on canvas, 71 x 120 x 3″. Courtesy of Parker Gallery, Los Angeles. Franklin Williams is the quintessential contrarian artist. He has maintained a meditative studio practice for sixty years, while living a committed family and teaching life, largely eschewing external pressure from institutional and market trends. The resulting unique work draws on the folk and craft traditions that he learned in his close Utah family.

Cutting Apron Strings, which speaks to the imminent demise of his mother, has intricate stitchery on pieced-together fabric. The stitchery is open, curved, patterned and lyrical–silver on a geometric ground of red, blue, purple, and black. The diamond shape has the lower half folded open as if the life within is still present.

In Pink Tea, a tribute to his family, created in acrylic and twine, the sexualized central image is the generative rising force that bears heart-shaped offshoots. Williams was an undiagnosed dyslexic in his youth, and also challenged by undiagnosed color vision deficiency. He recalls studying geometric patterns under a quilting frame as a young child. Family encouragement of his artistic efforts laid the base for his future development.

The love and support of his wife, Carol, to whom he has been married sixty years, is the inspiration for much of his work. Twins (71 x120 x 3 inches), which features two mirror images of a dancing figure, is executed in acrylic on canvas. The shared joy of the feminine figures is palpable, and the brushwork of dots and dashes brings to mind the stitchery that is so prevalent in many of his pieces.

Secret Sweet Slovakia, one of the most recent pieces, picks up techniques that are present in earlier works from the sixties. Crochet thread, feathers, acrylic, vinyl, and paper are a few staples of Williams’ intuitive process. Often his handprints and fingerprints appear in the works, both as a patterning device and as a literal representation of his hands at work. It’s about Love is an apt title for this singular exhibition, which clearly shares with us Williams’ central tenet: “To this day I’ve been a dreamer and I believe in magic.” This writer encourages you to experience this unique visual gift.

— B. Amore

- Seeing Landscape

Lapin Contemporary, North Adams, MA • lapincuriosities.com • Through December 28, 2024

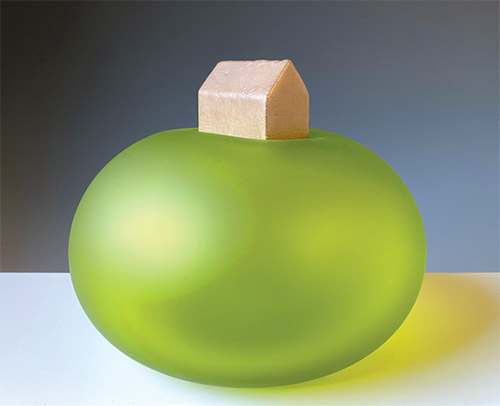

Jen Violette, Large Hilltop Barn, 2024, blown glass and bronze, 6.75 x 8 x 8″. Courtesy of the artist. This seemingly disparate, yet smartly edited exhibition is the fourth at what Cristina Barbedo calls her “emerging gallery” founded last April in North Berkshire’s historic Norad Mill. A Brazilian-born ceramist turned jewelry designer, Barbedo seeks out (by networking and trolling social media) visual artists who catch her eye, then links them with others who share stylistic or narrative traits to curate an exhibition. In this case, it’s a photographer, multimedia artist and graphic designer in Seeing Landscape.

John Lanterman, a Berkshire landscape architect for whom photography plays a supporting role, is the show’s lens man. His black-and-white images are riveting for the way cloud-splashed skies spill light over hills, meadows and groves of trees. In one, a tiny fragment of the moon hangs above roiling masses of shadow and light. In another, sunlight animates shimmering crowns of aspens.

Wilmington, Vermont-based painter and glass artist Jen Violette uses barn-shaped structures as visual tropes in multiple paintings and blown-glass pieces of blue, tangerine and lime. Often they rest on pillows of glass. In one significant departure, she positions a grove of glass trees in a grid suggesting human order imposed on nature.

Graphic artist Douglas Gilbert is Barbedo’s husband and business partner. They relocated from New York to Williamstown in 2022. His signature logo, a rabbit or lapin, inspired the gallery name. Gilbert coaxes shadowy, black-and-white images of hills, meadows and trees from thickets of crosshatched charcoal lines and dashes.

Although widely different in their chosen media, the three artists share common ground in expert craftsmanship and rural subject matter.

The rural aspect extends to mountain views visible through the loft gallery’s massive windows in the Norad Mill. Built in 1863 to process wool, the four-story mill is now a small-business shopping center. Its location on the Route 2 “Cultural Corridor” between MASS MoCA in North Adams and the Clark Art Institute in Williamstown is a strategic advantage, Barbedo says, in attracting New York and Boston-based visitors who tend to buy art. She also makes diverse use of the loft space with a studio for her jewelry making and a gift shop stocking her work and that of her husband as well other artisans.

“It’s all a work in progress,” Barbedo said. “I hope to grow a gallery.”

— Charles Bonenti

- Awre Journey: Twentieth-Century Afri-Caribbean Migration

Housatonic Museum of Art, Bridgeport, CT • housatonicmuseum.org • Through February 21, 2025

Iyaba Ibo Mandingo, Every day new people arrived, looking for work, any kind of work. 2023, acrylic on panel board. In Awre Journey: Twentieth-Century Afri-Caribbean Migration, Afri-Caribbean (1) artist Iyaba Ibo Mandingo tells the story of his ancestors’ immigration to Europe and North America and his immigration to the U.S. The paintings (2020–2023) in Awre Journey are also an ode to African American artist Jacob Lawrence’s The Migration Series (1940–1941), sixty panels that chronicle Black Americans migrating from the Jim Crow South to the industrial North.

Mandingo has studied Lawrence’s work and writes, “[Lawrence’s] dynamic cubist style brings each panel to life with sharp angles and primary colors….[he] created captions…that told the entire story.” (2) Like Lawrence, captions accompany Mandingo’s uniformly sized paintings. Awre Journey, however, features an extra panel because as Mandingo was completing the series, Harry Belafonte died, prompting a group portrait of Sidney Poitier, Cicely Tyson, and Belafonte to “mark the passing of three legendary Caribbean-American icons.” (3)

While the back gallery features additional work by Mandingo, Awre Journey inhabits the front room, hanging in an expansive, storyboard style grid. The chronological narrative begins in 1908, takes us through the Windrush Generation—approximately a half-million Caribbean people coming to Britain (1948–1970s)—and then illustrates Mandingo’s childhood experiences in Antigua and the U.S.

Visually, Mandingo strikes a thoughtful balance between the artist’s own style and Lawrence’s. Some works incorporate The Migration Series’ iconography, including “grips” (English suitcases) and birds; and Mandingo’s last panel mirrors Lawrence’s (a crowded railroad station, captioned “And the migrants kept coming”) with Afri-Caribbean people in a boat on choppy water, captioned: “But we continued to come, risking everything, hoping for better tomorrows.” Mandingo also selectively introduces some of Lawrence’s formal qualities, including facial features rendered with thick brushstrokes. Many of Lawrence’s faces in Migration had minimalist or no features, yet all of Mandingo’s Afri-Caribbean visages are detailed and express emotions such as joy, exhaustion, and affection. Interestingly, Mandingo draws no features on the white faces, a motif that concomitantly operates as a nod to Lawrence; a symbolic erasure of hegemonic narratives about immigration; and a recentering of Afri-Caribbean people and the important stories they hold.

— Terri C Smith

(1) This article uses the artist’s preferred term “Afri-Caribbean”: “For me Afri-Caribbean is a counter to the labeling Afro-Caribbean…defining ourselves is an important part of identity.” (email from Mandingo to the author). (2) Unless otherwise attributed, quotes are from the exhibition’s wall text. (3) Email from Mandingo to the author

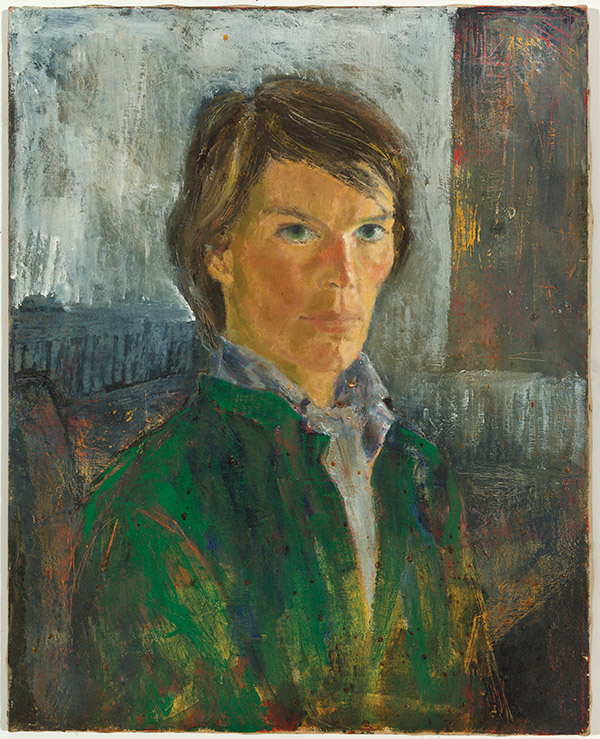

- The Aplomb Project

Aplomb, Dover, NH • aplombgallery.com • Ongoing

Stitched Together, 2024, painted by Danielle Festa with crocheted element by Sravya K, oil on linen. Courtesy of the artist. In the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, portraitist Danielle Festa painted the first in an ongoing series of portraits depicting trauma survivors, a series now known as The Aplomb Project. What started as a personal project has grown into a gallery space, a non-profit organization and an international community of survivors and supporters with Festa at the center.

Festa takes inspiration from classic works of portraiture, chosen by the people she paints. Her subjects are given a voice throughout the process. They make playlists for her to listen to and choose colors used in the piece. Part of what makes The Aplomb Project so unique and personal is that, after the portraits are exhibited, they are gifted back to the subjects. “This is going to end up on their walls, and it’s supposed to be a reminder of their strength, so it makes sense that they would have a lot of input.”

The survivors choose their own, often visually arresting, outfits. “The importance of what a survivor wears is really critical to their own feeling of self-worth and their newfound confidence matches their exterior,” said Festa, who incorporates textiles into her work, allowing her subjects’ clothes to leap off the page. For Stitched Together (2024), the subject Sravya K crocheted her own dress, and gave Festa a piece of the dense black knitwear to use in the work.

Festa is conscious of potentially triggering content while still encouraging survivors to share their stories. In the gallery, the survivors’ stories are located on a small screen, and visitors can choose to read them or not. Festa hosts workshops at her gallery in Dover where attendees engage in artmaking with the guidance of experts under a model of trauma-informed care.

In a world that too often shies away from even saying words like rape, incest and sexual abuse, perpetuating the shadowy culture of silence and denial in which these atrocities thrive, Festa’s work shines a light into that darkness. Yet, despite the nature of these topics, it is not through violent imagery that Festa reaches her audience. Instead, Festa invites us to the conversation through lovingly crafted depictions of survivors, standing proud, with aplomb.

— Autumn Duke

- Overview

The Tomaquag Museum, Exeter, RI • tomaquagmuseum.org • Ongoing

The Tomaquag Museum is located in a white farmhouse-style building nestled in the woods of Arcadia Village in Exeter, Rhode Island. Founded in 1958 by Princess Red Wing, a Narragansett-and-Wampanoag historian, and the anthropologist Eva Butler, the Museum is dedicated to Indigenous culture and history, with a particular focus on the communities of southern New England—including the Narragansett people, the only federally-recognized tribe in Rhode Island. In 2016, the Museum received the National Medal for Museum and Library Service (a framed photograph of Michelle Obama presenting the award to board member Christian Hopkins and the museum’s executive director Lorén Spears sits on a table by the entrance).

The name “Tomaquag” comes from the Narragansett word for “beavers,” an appropriate name for an organization that presents the concept of indigeneity as part of a complex and interconnected system. Within the interior gallery space, different displays engage with various aspects of social life—such as food, clothing, and trade—which are intertwined with the region’s natural resources, emphasizing the harmony between culture and nature. Additionally, the museum showcases the rich cultural production of southern New England communities through displays of intricately-woven basketry, pottery, historical and modern regalia, and an array of ornate beadwork pieces. Exhibits also highlight the Indigenous history of the region by featuring the lives and achievements of prominent figures and leaders from Rhode Island.

Objects on display are referred to as “belongings,” underlining their personal and human connections. The museum staff excel at contextualizing these belongings within Indigenous culture, effectively bridging historical narratives with contemporary matters. This emphasis on Indigenous voices is a distinctive feature of the Tomaquag Museum. Through first-person accounts, community members can share their memories and experiences, giving them control over their own history. Moreover, the museum highlights current Indigenous artistic and cultural production in New England by promoting the works of contemporary artists and hosting storytellers and speakers.

The Tomaquag Museum plans to relocate to a new site on the University of Rhode Island campus in Kingston in the near future. The new facility will enhance the museum’s capacity to engage and connect with the public and serve as a hub for research. This expansion will also ensure that the Tomaquag Museum continues its vital role in preserving and celebrating Indigenous heritage in New England.

— Michael W. Zhang

- Belle Terre: Jennifer M Johnston, Jonathan MacAdam, Colleen Pearce

Three Stones Gallery, Concord, MA • threestonesgallery.com • Through November 24, 2024

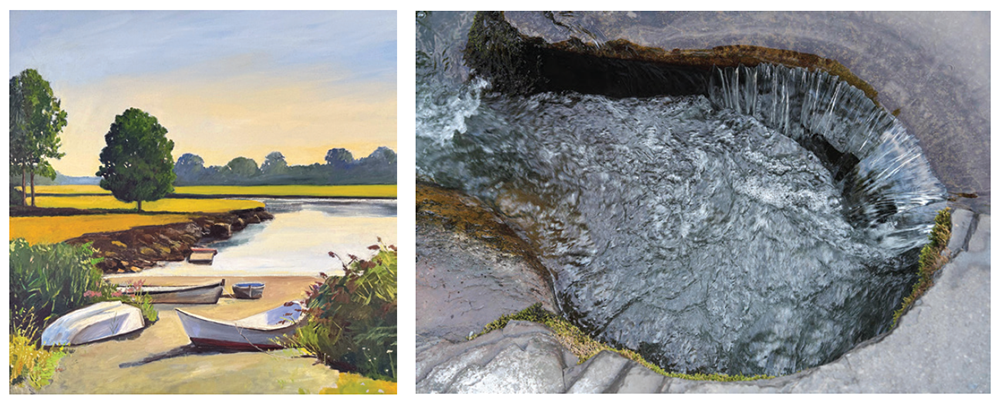

Above, from left: Jonathan MacAdam, 2024, Boat Yard Essex, oil on canvas, 24 x 24″. Jennifer M Johnston, Catskills I, 2024, archival ink jet print, limited edition. Courtesy of the artists. Belle Terre is Italian for “Beautiful Lands.” This exceptional exhibition could not have a better title. The range of work, from the almost abstract photography of Jennifer M Johnston to the soft realism of Jonathan MacAdam, to Colleen Pearce’s expressionistic paintings, shows viewers the beauty and love that the artists have for this earth—a place we are so fortunate to inhabit. This exhibition sharpens our appreciation and helps us to see anew.

MacAdam, born in London, shares his beloved Concord River, an oil on canvas painting that leads us from the wide triangular foreground of blue water to reflections of the river banks on either side, curving to a vanishing point of mystery. Marsh at Dusk, an impressive 36 x 72 inch painting gives us a wide vista, while Boat Yard Essex is a more intimate portrait which still continues the theme of peaceful, reflective water.

Johnston’s photographs of water in nature border on the surreal. Catskills II shows us sheets of water spilling over an edge of rock. The water’s luminescence is filled with shades of grey, lavender, and white—a “scene within a scene.” Catskills I captures an unusual circle of stone with clear water falling from the sides and filling the center with dappled texture and light. Higgins I looks as if it is another water portrait, yet is actually a photograph of colorful rock striations in rust, blue and grey. The photographer’s eye sees in a unique way and provides us a fresh view of the natural world.

Earth arranging her Summer Skirts, by Pearce, is a seductive oil on Yupo paper painting that offers us the jumbled lushness of blooming flowers and curling, reaching leaves. Pearce’s Thunder Hole, a dynamic painting of a rock formation that opens into the ocean under a sky of swirling clouds pulls us skyward from the earthbound stone.

Three Stones Gallery, named by Jennifer Johnston for the trilithon that forms the center of Stonehenge, is a perfect venue for this exciting exhibition which embraces the many vicissitudes of the Earth’s beauty. A stunning show that takes your breath away!

— B. Amore

- The Elusive Art of Kumi Yamashita

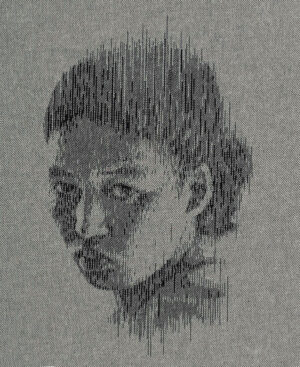

Flinn Gallery, Greenwich, CT • flinngallery.com • Through November 6, 2024

Warp & Weft (Mother No. 2), 2013, fabric with threads removed,15 x 13″. Photo: Paul Takeuchi. Opening the Flinn Gallery’s 2024–25 season, The Elusive Art of Kumi Yamashita offers a glimpse into the contemplative vision of Yamashita, whose work explores her fascination with the human form and human condition. She’s been described as a “conceptual humanist,” and owns it: “I think that might be one of the best descriptions of my work and subject matter,” she says. The process of bringing these ideas to fruition is a painstaking one, although the work comes to Yamashita “fully formed.” Then, she says, “I see my job as attempting to faithfully transfer that vision into the physical world.” Exhibition viewers can expect to see subtly provocative works that embody this approach.

Yamashita’s “Light & Shadow” series suggests the nonphysical underlayer of image, reminding us that nothing is static. Light is both illumination and life force—shadow and light are mediums. Carved wood numbers affixed to the wall, strategically illuminated to suggest a face; all is positioned to give definition to human form, with echoes of shadow boxes and early photography. Yamashita’s portraits are no ordinary portraits: taking the concept of pointillism to a three-dimensional level, Yamashita “draws” with thousands of galvanized nails and a single thread that connects them, coalescing like a constellation atop the image. These threads are both literal and metaphorical: “Experiencing common threads that connect us all has always been an inspiration for my creativity,” Yamashita says.

Born in Takasaki, Japan, Yamashita currently lives and works in Woodstock, NY. Her work is held in the collections of institutions the world over, including museums and corporations. In the Flinn Gallery iteration, curator Leslee Asch hopes viewers will “expand their understanding of the possibilities of the varied media [Yamashita] skillfully employs, and the breadth of her vision.”

As philosophers and artists have long understood, without light, there is only darkness. As Carl Jung said, “Everyone carries a shadow, and the less it is embodied in the individual’s conscious life, the blacker and denser it is. If an inferiority is conscious, one always has a chance to correct it.” Yamashita speaks beautifully to this individual—and collective—truth.

— Julianna Thibodeau

- Life Forms

Corey Daniels Gallery, Wells, ME • coreydanielsgallery.com • Through October 15, 2024

Celeste Roberge, Rising Seas(onal) Collection: Seaweed Will Be Lapping at Your Doorstep #2, 2023, seaweed and wax over wax cast Muck boots, each boot, 18 x 5 x 13″. Courtesy of the artist. Life Forms, a series of exhibitions that will take place in different venues across Maine over the next four years, kicks off with this showcase of the twelve artists in the collective: Leah Gauthier, Jackie Brown, Lynn Duryea, Kazumi Hoshino, Elaine K. Ng, Bronwen O’Wril, Ashley Page, Veronica Perez,

Celeste Roberge, Naomi David Russo, Ling-Wen Tsai, and Erin Woodbrey. It’s a diverse and brilliant line-up.Roberge’s Seaweed Will Be Lapping at Your Doorstep #2 envisions the future by way of a pair of wax cast seaweed-covered Muck boots—“imaginative survival gear,” she calls them. In a like manner, Woodbrey presents single-use plastic containers for surface cleaners and water, covered in ash, plaster, and gauze—effigies of consumer goods (or bads).

By contrast, Russo offers fanciful practical creations, Squiggle Mirror and Coil Lamp, each incorporating curved elements that enhance the wall fixtures. The small white oak pieces in O’Wril’s Pick Me Up also play on curvature, smooth shapes that might be part of a puzzle. Elsewhere, Page’s wire constructions, Black and Porous and Black Seed, are loose and linear.

Duryea’s terracotta Slant #19 and Tilt are soft-toned and engagingly off-center—constructivist yet warm—while Brown’s 3-D printed ceramic sculptures Twister and Elemental, from her “Strata” series, are rough-hewn and organic. Hoshino’s Fragments of Memory highlights the textures of light and dark stone via an arrangement of five small tabletop sculptures.

Tsai’s Chair and Bench from her “Rising/Sinking” series might be stage sets for absurdist dramas, the simple wood furnishings embedded in square light-blue milk-paint platforms. Perez’s large-scale suspension, made from artificial hair, wood, and burlap, also seems theatrical, the conceptual centerpiece for an existential one act.

Wall works include Gauthier’s silk thread-on-linen pieces with acrylic and gouache, hypnotic in their circular precision/arrangement. Ng takes a different route, using plant-dyed cotton and eri silk to evoke silky rocks, a lumber pile, and a greenhouse roof.

Almost all the work in the show dates from the past couple of years. Future iterations of Life Forms promise to trace the evolution of this

dynamic dozen. Learn more about the series at lifeformsart.org.— Carl Little

- Vivien Russe: Networks

Sarah Bouchard Gallery, Woolwich, ME • sarahbouchardgallery.com • Through August 4, 2024

Vivien Russe, Networks, 2022, acrylic on panel, 10 x 10″ each. Courtesy of the artist. Juxtaposition is an artistic tradition dating back at least to the Surrealists who used it to create dreamlike imagery that created a sense of disorientation. Over the years Portland, Maine-based painter Vivien Russe has built her acrylic paintings around contrasting elements, placing side by side two or more images that play off against each other to create intriguing visual frissons. Some of them recall poet Allen Ginsberg’s “eyeball kicks,” defined as “the juxtapositions of disparate images to create a gap of understanding which the mind fills in with a flash of recognition.”

Russe’s show at Bouchard features several juxtapositions. In Again (Diptych), 2022, she pairs unfurling fiddleheads with an image of two small water-filled saucers. The coupling offers a challenge to fill that “gap of understanding” that lies between forms of nature and manufactured glassware.

Dispersed #2 (Diptych), 2022, combines fern fronds with what appears to be a transparent flower form set against a checkerboard pattern. This painting and two related pieces, Dispersed #1 and Dispersed #3, evoke the dissemination of seeds. They underscore what Russe says is the root of her recent work: the climate crisis and the damaging effects of human activity on the natural world and the planet.

Russe traces inspiration for the work to a visit to Acadia National Park in 2018 and a trip to view Renaissance paintings in Italy the following year. In Finding (Diptych), 2021, she places a study of lichen alongside a schematic of a dome. In doing so, she answers her own question: “Why is a lichen less holy than St. Peter?”

Moss and Maple, both 2023, celebrate the resplendence of the natural world. The former highlights bright green ground cover, the latter, elements of the tree: seedlings, fall-burnished leaves, flowers.

Russe presents a darker vision in one of her most recent pieces, In Memory Of, 2024. Here, fungus appears to spread over an old headstone. The artist admits to being discouraged by “the increased environmental degradation from political divisions, capitalism, population displacement and war,” yet her work,

so strikingly conceived and composed, carries a distinct visual pleasure.

And there you have it: the paradox of the world we live in.— Carl Little

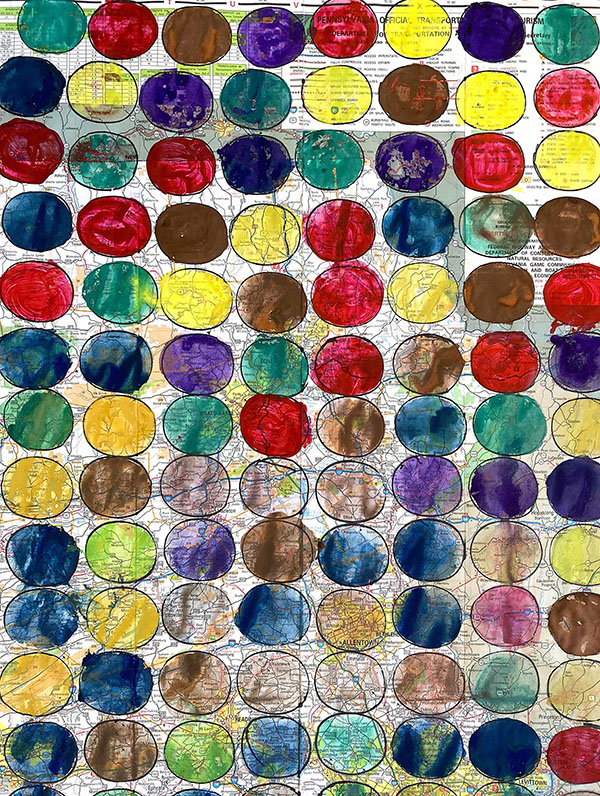

- Scraps With Nature – Mary Admasian

T. W. Wood Gallery • Montpelier, VT • twwoodgallery.org • Through July 22, 2024

The Red Divide, 2024, maple, layered plywood, bandsaw blade, graphite, acrylict, 17 x 81/2 x 4″. Mary Admasian’s body of multimedia work is on the move to new heights. Known for creating in the spirit of environmental and social/political activism with intentions that run deep, these sculptures allow the viewer to come to their own understanding. Admasian shares, “I call myself a seed planter. I use materials as a metaphor for other things.” Scraps With Nature at the T. W. Wood Gallery reveals true architectural mastery in sculptural assemblage. At first glance, structural lines and a limited color palette (primarily natural wood, blue, black and white) reveal texture that allows the voices in the reclaimed scraps of wood to sing. While small in scale, the thirty-one pieces are at once elegant in surface and line and command attention. The exhibition merges celebrated series of her work as well as fourteen new constructions. As for her palette, Admasian is known for using the same blue in her work that marks trees for felling. However, the blue in her constructions signifies a rebirth of the wood in a new form.

Upon closer viewing, stones, pearls, and natural crystals have a relationship with the wood. A favorite title in the exhibition is Pearl on Deck—its shapes reminiscent of a boat bottom with a pearl added to draw energy to the sculpture, revealing the artist’s playful side.

Barbed wire makes an appearance to represent tension or division in works like Bound by History and The Red Divide. “I am influenced by the exploration of balance and barriers between objects—positions and connections—as well as implicit boundaries of familial, political and social covenants and connections.” Admasian’s black and white multimedia pieces have a unique energy created with needles and black ink on a surface that emits energy and transcendence. Her repurposed piece from Vermont’s Highland Center for the Arts on the solar eclipse employs gossamer paper—a layered eclipse evolution—searching for totality. A perfect homage to her home state of Vermont which celebrated this celestial experience in the line of totality.

— Kelly Holt

- What, Me Worry? The Art and Humor of MAD Magazine

Norman Rockwell Museum, Stockbridge , MA • nrm.org • Through October 27, 2024

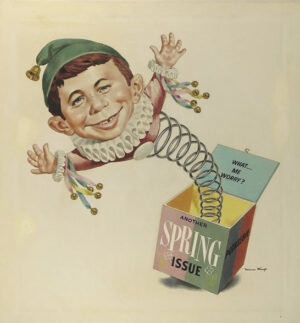

Norman Mingo (1896-1980), What, Me Worry: Another Spring Issue, 1957. Cover illustration for MAD #33, (EC, 1957), acrylic on board. James Halperin Collection, Courtesy of Heritage Auctions, HA.com. MAD and all related elements ™ & © E.C. Publications. Courtesy of DC. All Rights Reserved. Used with permission. In a fraught election season, this retrospective on the art of pioneering counter-cultural MAD magazine illustrates how laughter can be a tool for social and political change. Co-curated by the Rockwell’s chief curator Stephanie Haboush Plunkett and illustrator/art journalist Steve Brodner, it showcases over 250 images by more than thirty artists in a dense, yet comic, multilayered exhibition that says as much about artistic collaboration as it does about lampooning American culture.

Launched in 1952 by editor Harvey Kurtzman and publisher William Gaines as an EC comic book series, MAD was converted to an illustrated magazine in 1955 to skirt potential censure by the industry’s Comics Code Authority. Aimed at young readers with a goofy, gap-toothed cover boy named Alfred E. Neuman as a ubiquitous presence, MAD hit a peak circulation of over two million in the 1970s, despite lawsuit threats and an FBI investigation. After 585 published issues, it continues today in curated reprints and a legacy of late-night television comedy.

Illustration art is story-driven, so viewers will scan hundreds of captions, narrative bubbles and wall texts as they navigate work by generations of artists, including a few women, who contributed to MAD. Theirs was a world in which writers pitched story ideas as blocked-out movie scripts that artists were later hired to visualize.

“It was done with tremendous care and skill,” said Brodner of the discipline required to take narrative direction and come up with arresting images on tight deadlines.

Mash-ups of subjects that do not normally go together mock correctness. Richard Williams’s substitution of MAD’s Neuman for the figure of Norman Rockwell in the latter’s 1960 Triple Self Portrait or the gorilla face Roberto Parada put on Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring are two examples.

Superbly drawn caricatures by Mort Drucker reprise the political power of the Sixties-era Kennedy family and the criminal reach of the Italian mafia in the 1972 film The Godfather, renamed “The Odd Father.”

By the 1990s, digital technology made pictorial changes easier and cut production time, though made “dinosaurs” of human artists, complained Brodner, saying, “no robot could do what they did.”

— Charles Bonenti

- Deserve What You Dream

NXTHVN, New Haven, CT • nxthvn.com • Through September 1, 2024

Installation view of Deserve What You Dream.

Photo: Chris Gardner. Courtesy of NXTHVN.Too often, exhibitions disregard a viewer’s body. Critic Brian O’Doherty famously noted this in his 1976 book Inside the White Cube. “The space offers the thought that while eyes and minds are welcome, space-occupying bodies are not.” With Deserve What You Dream, curator Marissa Del Toro centers the visitor’s body and encourages resting and daydreaming as forms of resistance, which she posits is especially important for Black individuals and people of color. The introductory signage shares that this exhibition—with works by Derrick Adams, Isaac Bloodworth, Jihyun Lee, and Sarah Zapata—is inspired by Tricia Hersey’s 2022 book, Rest is Resistance which “proposes [that] when we allow our bodies to rest and nap, we resist the status quo and provide ourselves ‘a portal to imagine, invent and heal.’” Deserve What You Dream is such a portal, creating comfortable-to-cozy areas for reading, drawing, and contemplation throughout. By placing artworks in a lively conversation that wisely resists literal exposition of the show’s themes, the curation invites visitors to splash around in what Hersey has described as the “spiritual and somatic dimensions” of rest as resistance.

Play is foregrounded at the entrance with Bloodworth’s lighthearted, street-facing mural, featuring blue waves and “Joy the Black Boi” on a floatie. Upon entering the lobby, Lee’s doll-filled shelf sculptures continue this sense of play. The exhibition also features her surrealist sketches that bear out Lee’s approach of

“maximiz[ing] the specific state between reverie and reality.” Water, a symbol of the subconscious, appears again in Adams’ Floater paintings where adults are poolside with animal-shaped floaties. The only purely abstract works here are by Zapata, a Peruvian-American artist who explores identity, labor, and culture. These include large-scale, color field textiles that resemble shag rugs; fabric works from her “Gargoyle” series—exquisitely crafted interlopers that hug corners and melt down walls; and her site specific installation “A resilience of things not seen,” a sitting area that is as much a hug as a respite, not only anchoring the main gallery, but the bodies that rest there.— Terri C Smith

- “Tricia Hersey: Rest and Collective Care as tools for Liberation,” on Sounds True channel, YouTube, 2021.

- From artist statement on Jihyun Lee’s website

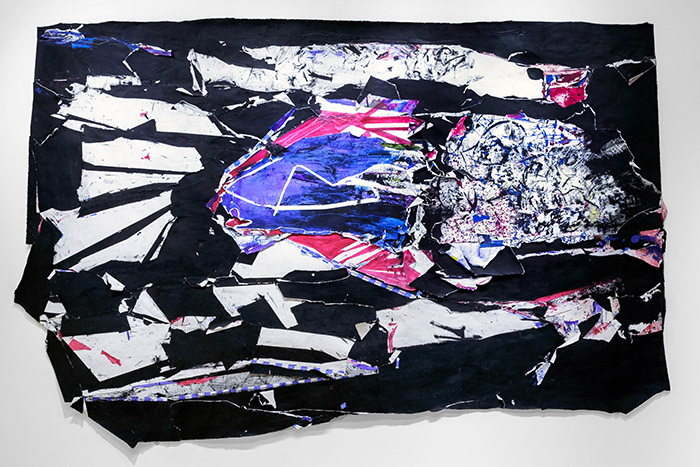

- Material Matters

Vermont Supreme Court Gallery, Montpelier, VT • vermontjudiciary.org • Through June 28, 2024

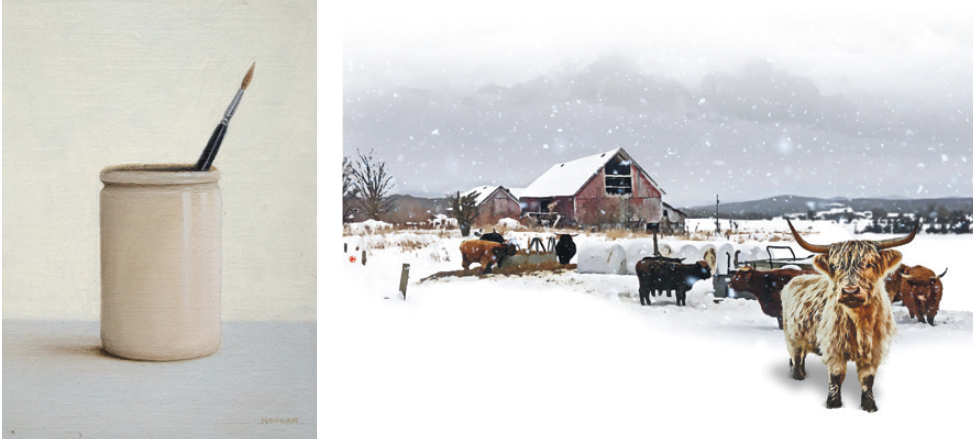

Victoria Blewer, Solitary Barn, 2023, hand-colored photograph, 15 x 12″. Courtesy of the artist. Form meets fantasy in Material Matters—Victoria Blewer’s solo exhibition at the Vermont Supreme Court Gallery. This exhibition, delayed first by the pandemic and then the 2023 flood in Montpelier, is worth the wait. Blewer, originally from New York City, moved to Vermont in the late 1980s. She is an acclaimed artist—receiving quite a few national and regional awards. One of her muses is the celebrated author Chris Bohjalian, her husband.

Inspired by a glance at a bumper sticker, “‘Change is inevitable. Growth is optional.’ And isn’t that what every artist strives for?” Blewer shows in two distinct bodies of work that she is pushing the boundaries of her medium with a bold visual vocabulary.

Her series of barns show her depth of photographic study in analog techniques. In this series Blewer is using silver print black and white barns, hand-colored with oil paint. In the work New Barn (2024), the architectural lines and symmetry create a beautiful formality while the play of color in the work vibrates with the push/pull of what is in the foreground and what is behind the barn. Blewer masterfully creates geometric shapes within the barns to break up the shapes with color. As a group, the barns are a delight of color theory meeting the lovely texture made by Kodak’s 35mm infrared film.

Lining the halls of the gallery are Blewer’s collages. Leading the eye back and forth in time using faded photography, newspaper clippings with antique adds, geometric patterns and wildlife. The collages are whimsical while making a statement on society—women’s roles ever-changing, how we govern, how we decide. Characters in stilettos wearing helmets prepare for battle. Street photography beckons the viewer to “Question everything, Leave your baggage here” with an all-knowing eye and flying UFO objects in the sky with a comic book character urging “C’mon son! Use your common sense! Think it through!,” bring the viewer on a time-travel journey. One favorite features a dark, grainy painted background with organic circular forms which almost feel like printmaking. A collaged bird floats upside down withing and old tinted landscape, the bird’s eyes are glancing up at a sign that reads “HOPE.”

— Kelly Holt

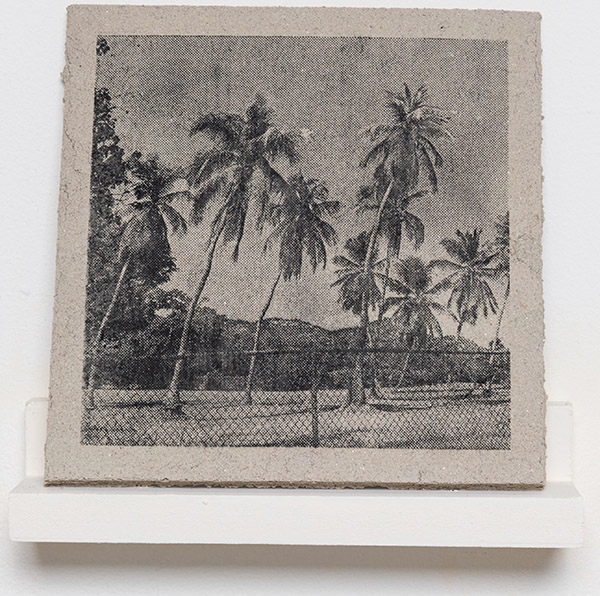

- Jungil Hong: The Time Being

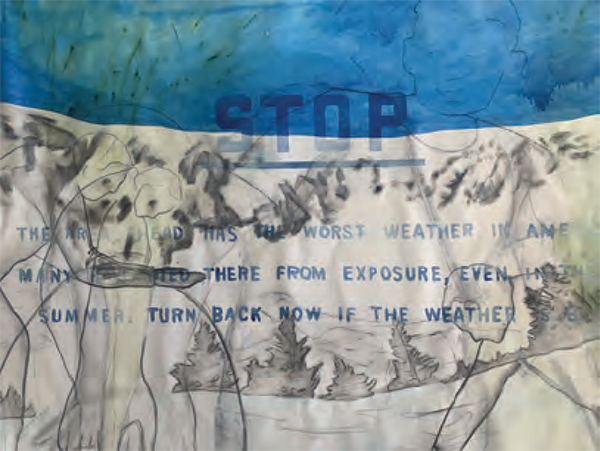

ODD-KIN, East Providence, RI • odd-kin.com • On view May 19, 2024

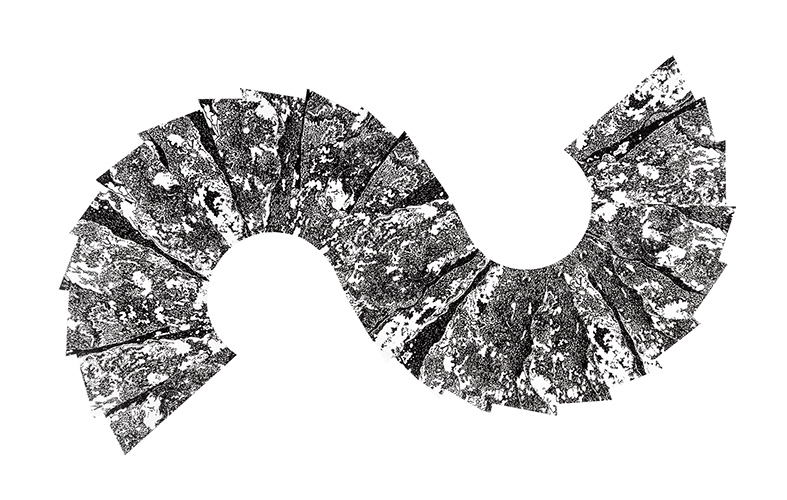

Jungil Hong, Snake Den Mesa, 2005, screen printed collage, 6 x 8′. Courtesy of the artist. Jungil Hong, a Korean-born, Providence-based artist, is reemerging in Jungil Hong: The Time Being. Both retrospective and introspective, the exhibition examines and reexamines Hong’s personal life and career. She got her start in collaborative live-work spaces like Fort Thunder, spaces that defined the art scene of Providence in the 1990s. Yet things have changed since then. “In the time between oldest and newest work in the exhibition I have questioned parts of my identity—as an immigrant, a mother, a daughter, a partner, an artist,” said Hong.

Hong repurposes and reimagines projects from different parts of her life. Jacquard weavings done during her time at the Rhode Island School of Design are given new life as sculptural objects, their beauty allowed to flourish beyond the constraints of their original purpose. Pieces from pivotal moments in her career make a reappearance, such as Between San Souci and the Setting Sun, a collage on wood made for the 2007 deCordova New England Biennial.

Table of Objects holds objects relating to road trips and watching movies as well as those found in nature and representing the passage of time. Some were made by Hong’s mother, whose presence can be felt throughout the exhibition. Hong’s Selfies and Portraits series explores the physical changes of the body over time, a thing of both anxiety and beauty for Hong. “For one who cherishes the accrual of time, I never imagined I’d fear the passage of years. I gather lines and dots, mapping the story etched on the surface of my existence, artifacts of fortunes of living.”

This show shines new light on the life and career of a woman foundational to the Providence art community. More than that, however, it offers a window into an artist’s two-decade journey of identity and self-discovery. “The exhibition explores the significance of parenting, being parented, projecting oneself onto others, absorbing what is given to you, being an immigrant, not having enough, having too much, comparing, and reflecting.” Viewers will see, perhaps, a little of their own journeys through time reflected in Hong’s evocative and expansive body of work.

— Autumn Duke

- 40 Years of Collecting

Cahoon Museum of American Art, Cotuit, MA • cahoonmuseum.org • Through December 23, 2024

Daisy Marguerite Hughes (1882–1968), Cape Cod Dunes, n.d., oil on canvas, 37 x 45″. Collection of the Cahoon Museum of American Art. Gift of the Cahoon Society, 2013 2013.2. This year, the Cahoon Museum of American Art marks its 40th anniversary. In 1984, the museum opened in the former home and studio of folk artists Ralph and Martha Cahoon, and embarked on assembling a permanent collection. To celebrate the milestone, the museum has brought forth from storage an enticing array of works in varied media, with varied themes, stretching from the 1850s to the present.

With its maritime focus, the first room opens with Sunset in the Arctic by William Bradford, a Hudson School artist who ventured to the Arctic several times in the 1860s, which portrays a white colossus, amid pink-hued clouds, towering over the sailing vessels at the horizon. Alongside Bradford’s painting Bradford’s Iceberg, a small ceramic sculpture by the contemporary artist Valerie Hegarty mimics the behemoth, only it’s melting off the frame. The demise of the seemingly indestructible iceberg conveys that all things great and small contend with nature’s flux and fragility.

In the idyllic, Pissarro-like scene of Duxbury Clam Digger, Daniel Santry portrays the hard edges of the working man’s humble life. For Cape Cod vistas, there’s the chockablock Provincetown Waterfront by the early Modernist Nancy Ferguson and Daisy Hughes’ boldly rendered Cape Cod Dunes. In Truro-based Robert Cardinal’s remarkable Three Boats, sky and sea—without horizon—are one bright blue, ethereal space, imparting an abstract feel.

The homespun theme of the second room embraces folk art by pairing the classic portraits by Ralph Cahoon with Dorothy Davis’ later day paintings of young children. The room nods respectfully to Impressionism with Paul Moro’s thickly painted Gladiolas and Zinnias, a still-life blaze of lush flowers—even the table seems to shimmer—and with the calming In the Hills and the energized Trout Brook by the masterful American Impressionist John Enneking.

The depiction of a quaint mid-20th-century town in Cotuit Port Crossing by Wilson Barnett is balanced by A Matter of Time, Marieluise Hutchinson’s bucolic scene with a hint of Hopper.

Displayed in the museum’s intimate historic wing, the small yet wide-ranging exhibition is a prideful expression of the care and commitment that enabled the museum to grow its collection for the benefit of Cape Cod and beyond.

— Jack Curtis

- Nora S. Unwin: A Retrospective

Monadnock Center for History and Culture, Peterborough, NH • monadnockcenter.org • Through September 28, 2024

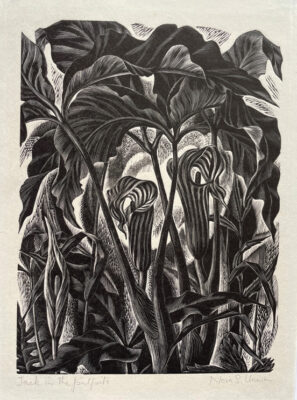

Nora S. Unwin (1907–1982), Jack in the Pulpits, c. 1954, wood engraving, 73/4 x 53/4 “. Photo: Collection of the Monadnock Center for History and Culture. The works of twentieth-century engraver and illustrator Nora S. Unwin (1907–1982) can be found at a roster of famous institutions—the British Museum, The Met, and the Smithsonian, to name a few. A wonderful and fitting surprise, however, is to discover that the world’s largest collection of her work resides at the Monadnock Center for History and Culture in Peterborough, NH, the town Unwin left England to visit in 1946 and quickly made her home.

The Center’s current retrospective features eighty of Unwin’s works in two rooms. The first room, arranged chronologically, includes already sophisticated drawings by a twelve-year old Unwin and enchanting early woodblock prints of animals and nature. Several of Unwin’s books are on display—she illustrated over 100 books and authored twelve—as are her engraving tools, and selected later works. The second room is arranged by major themes, including nature, spirituality, cats, and experiments in abstraction.

Most of the pieces are black-and-white woodblock prints, which Unwin typically hand-impressed, a practice demanding great precision to ensure print quality and consistency. Technically exceptional and richly detailed, her pieces are also emotionally evocative. Michelle Stahl, the Center’s executive director, says that, from a young age, the artist was able to convey emotional content with any subject, remarkably doing so “with basically the white of the paper and black ink.” In a print like Jack in the Pulpits, Unwin’s rendering of local flora flexes with the compressed energy of New England’s brief yet exuberant growth season.

Unwin came to Peterborough in 1946 at the invitation of her friend and frequent collaborator, American writer Elizabeth Yates. Artistically invigorated by the New England landscape, she decided to stay. She would live, teach, and create in New England (primarily in Peterborough) until her death in 1982. She left the contents of her studio (over 1,500 pieces including prints, engravings, books, sketchbooks, and collagraphs) to the Sharon Arts Center. Following a series of institutional mergers, the collection was donated by New England College to the Monadnock Center in 2022, fulfilling Unwin’s wish for her work to remain in her adopted hometown.

— Alix Woodford

- Dreams of a Common Language

Overlap Gallery and Project Space, Newport, RI • overlapnewport.com • Through June 15, 2024

Lu Heintz, Habitus, 2021-ongoing, wood, plaster, steel, fabric, plastic, paper pulp, and found objects, dimensions variable. Photo: Lu Heintz. Overlap is a dynamic new gallery located just outside downtown Newport in a refurbished glass shop. Co-directed by artists Susan Matthews and Alicia Renadette, Overlap is committed to showcasing work that highlights rigor in craft, creating a space for underrepresented art that features textiles, installations, and other material investigations often spilling off the wall. Their upcoming exhibition Dreams of a Common Language promises a unique interpretation of fiber arts which will continue to push the gallery into the forefront of Rhode Island’s art scene.

The exhibition features three Rhode Island-based artists and educators. Lu Heintz, Elizabeth Duffy, and Anna McNeary are united in their explorations of

gender, craft, and identity through textiles, installation, and performance. Dreams of a Common Language takes its name from an Adrienne Rich collection of poetry from which the three artists have taken to sending excerpts to each other as a grounding, meditative practice.Meticulous in craft, Duffy studies the cyclical nature of clothing through her current project Wearing. This series involves her carefully unwinding braided scrap rugs, ironing and patchworking tattered scraps, and metamorphosing them into garments and wall hangings. The works often remain tethered to the placental mass of the original rug, disrupting their use as either clothing or rug.

Tethering and transformation are reflected in McNeary’s performative works. She explores the vulnerability of social intimacy through modular clothing that links together participants. Additionally, McNeary utilizes screen printed textiles featuring repeated words such as “certainty,” “now,” and “never” to create quilt style wall hangings where words become abstracted. Like the connective clothing, the words undulate in and out of recognition and blur their function as statement or pattern.

Heintz continues the themes of transfiguration in her installation Habitus, a whimsical display of furniture and household objects. Closer inspection will reveal an organ-like plushie slouching in the chair, a red stocking dangling seductively off of a coat stand turned foot, and other bodily mirages that hint these objects may be anthropomorphizing.

The works of Duffy, McNeary, and Heintz are playful, transformative, and reject the language of object, artwork, and entity.

— Eleanor Q. C. Olson

- As the World Burns: Queer Photography and Nightlife in Boston

Tufts University Art Gallery, Boston, MA • artgalleries.tufts.edu • Through April 21, 2024

Mark Winer, As the World Burns, 1973, digitized super 8 film, 18:00 min. Courtesy of the artist. Presented simultaneously with Christian Walker: The Profane and the Poignant, As the World Burns: Queer Photography and Nightlife in Boston takes a deep dive into the photography of Boston’s queer scene from 1974 to 1984, corresponding with Walker’s time in the city. Defying genres, the exhibition unites fine art, instructional, vernacular, and documentary photography with experimental video and photographically derived textiles. Curated by Jackson Davidow, Ph.D., in collaboration with the TUAG curator, Laurel V. McLaughlin, the exhibition highlights a new presentation of photographically generated works formed from LGBTQ+ histories contextualized within Boston and its changing cityscape.

Upon entering, we follow Walker’s series The Theatre Project, a line of analog black and white prints diving into the cruising culture of the Pilgrim Theatre, the images reveal shifting scenes of lone figures dimly glimpsed and couples kissing. These photos set the exhibition tone–contemplative, passionate, considerate, and frank–often located on the streets of the Combat Zone, in nightclubs, and glancing in on intimate scenes.

On one wall, photographs highlight a single fashion show at Spit, a former nightclub on Lansdowne Street, where Gail Thacker, one of the performers, captured the excitement of readying for the night. The only depiction of the fashion show itself is Philip Phlash’s Mark Morrisroe, Pat Hearn and Friends, capturing the performers giddy on stage.

Images surround Mark Winer’s Super 8 film, after which the exhibition is named, As the World Burns (1973)–dreamlike and almost erotic, Winer envisions Bobby Busnach’s life as a hustler and others pictured throughout the exhibition. Haunting and hypnotizing, it is hard to look away, as music entices viewers into scenes of friendship intermingled with masturbation and sexually explicit flirtations.

Illuminating Boston’s unseen queer histories, As the World Burns expands the canon of the Boston School, first coined by Nan Goldin and solidified by Lia Gangitano and Milan Kalinovska’s exhibition The Boston School. As the World Burns expands this canon to include many previously unconsidered artists. Focusing on a single decade and inviting a new perspective on community, passion, and intimacy, Davidow unearths the history of LGBTQ+ artists in Boston.

— Abbi Kenny

- Fluid Matters, Grounded Bodies: Decolonizing Ecological Encounters

Gallery 360, Northeastern University, Boston, MA • camd.northeastern.edu/cfa/center-for-the-arts-exhibitions/ • Through April 6, 2024

Farah Al Qasimi, Um Al Naar (Mother of Fire), 2019. Digital video, 42 minutes and 7 seconds. Courtesy of the artist. Gallery 360, nestled into Northeastern University’s campus, presents this stand-out exhibition featuring artists Farah Al Qasimi, Beatriz Cortez, micha cárdenas, Tessa Grundon, Allison Janae Hamilton, Joiri Minaya, Ada M. Patterson, Wendy Red Star, Himali Singh Soin, Annie Sprinkle, and Beth Stephens. Originally presented at NYU’s Gallatin Galleries in July 2022, Northeastern’s team worked with the curators to re-envision the exhibition for Northeastern and Boston. The show spans two venues, Gallery 360 and Northeastern Crossing, a public-facing community-oriented initiative providing a space for students and residents. Aimed at deconstructing hierarchical and colonial narratives around climate change, this exhibition positions itself as a place for self-discovery and reflection on the current climate crisis.

Upon entering the corridor-like gallery sided by one long glass wall offering a view to passersby, we encounter Wendy Red Star’s collages from the series A Float for the Future (2021). Brightly colored fabric and images reimagine the Crow Fair Parade with an eye toward future potential. Arranged into four sections, the exhibition begins here with Counter-Histories and Mythologies of Place, then moves through Bodily Presence and Absence, Kinship as Remediation, and Beyond the Coloniality of Place.

One highlight is Farah Al Qasimi’s Um Al Naar (Mother of Fire). A 42-minute and 7-second video in a documentary-style reality TV format presenting a Jinn from Ras Al Khaimah, UAE. Through a combination of found footage and interviews in this strange and captivating video Al Qasimi explores local history, colonial history, myth, and issues of identity.

Throughout the exhibition, time becomes layered and compressed. Works like micha cárdenas’s Sin Sol/No Sun (2018) place the player in an augmented reality video game set in the year 2068, and Joiri Minaya’s collages combine historical and contemporary images of Dominican and Caribbean women and landscapes illuminating the legacy of colonialism.

In addition to community engagement spearheaded by Northeastern Crossing, an exhibition catalog will be available in early 2024. To be located in the gallery, the catalog will include three interviews with artists Cortez, Patterson, and Soin, providing visitors with an expanded view into the artworks and artist’s practices. This exhibition is an exceptional reason to visit and explore Northeastern’s campus.

— Abbi Kenny

- Radical Pots & Cooperative Hands: Katherine Choy and Clay Art Center

Greenwich Historical Society, Cos Cob, CT • greenwichhistory.org • Through February 4, 2024

Katherine Choy, ca. 1957, Pair of Bottles, left to right: Bottle with Donut Shape, stoneware, 9.5″; Long-Necked Footed Bottle with Thumb Hole, stoneware, 11″. Clay Art Center Collection. Photo: Paul Mutino. Radical Pots & Cooperative Hands: Katherine Choy and Clay Art Center is an exhibition that showcases the work of an incredible artist, as well as the stalwart community that she helped build.

Katherine Choy first came to America from China to attend college in 1946. By 1952, she had obtained bachelor’s and master’s degrees and became the head of the ceramics department at the Newcomb College at Tulane University. In 1957, she came into contact with Japanese-American potter Henry Okamoto, and soon after they founded Clay Art Center in Port Chester, NY. Tragically, Choy died of pneumonia at age thirty only one year later in 1958. Despite this hardship, Okamoto, the Port Chester community, and surrounding areas fought to keep Clay Art Center alive, and the nonprofit is a staple of the local arts community to this day.

Okamoto not only saved Clay Art Center after Choy’s untimely passing, he and the Clay Art Center staff also saved her work, notes, and her correspondence with Okamoto when the two were making plans for the Center. Many of these historical objects, including business documents, photographs and personal letters are on display alongside ceramic works by both Choy and Okamoto.