Frances Stark

Frances Stark, Pull After “Push,” 2010, mixed media on canvas on panel, 69 x 89″. Collection Nancy and Joachim Bechtle. Photo: Robert Wedemeyer.

“I couldn’t draw to save my life…It’s not like, oh, I had the talent so I pursued art,” says Frances Stark whose exhibit UH-OH: Frances Stark 1991–2015 is at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston and is part of #mfaNOW—their season of celebrating contemporary art and artists.

UH-OH originated at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles and features more than 100 works of this Los Angeles-based artist. Stark’s work is not media specific. Paper is very central, as is voice. And she uses whatever means is appropriate to get her message across—be it assemblage, video, drawing, PowerPoint or performance. Most of her work is text based and she describes it as “thought made manifest.” She comes to it “from the point of view of a poet, in a sense, as a communicator,” she says. She mines her own life for material whether it’s the junk mail that arrived in her office in Push (2006), the skunk that wandered into her kitchen and ate her cat’s food in Welcome and Unwelcome (2006), her school transcripts in Untitled (Self-portrait/Autobiography) (1992) or her virtual sexual relationships in the video for the 2011 Venice Biennale, My Best Thing (2011).

Stark has always been a reader and from the beginning her art has been “about carving out a space for the viewer of close reading.” Her works do require proximity—sometimes due to the text size, other times because her works can be enigmas—puzzles or riddles that require context or thought to comprehend.

Stark was born in 1967 and grew up in Southern and then later Northern California. Her mother worked for the telephone company and her father was an electrical engineer who worked in the printing business. Communicating has always been at the core of who she is. She studied humanities at San Francisco State University. It was during this time that she went to see a lecture by artist Mike Kelley and realized that he “somehow fused all of these vital models [of hers] like Henry Miller or punk rock…or a [Philip] Roth anti-hero.” Kelley became a mentor to Stark, and she studied with him at the Art Center College of Art and Design where she received an MFA. “I learned about art in a context,” she says, “…where the borders were very fluid and it was an all-encompassing umbrella. The art world provided this umbrella between philosophy and literature and politics. It was a very open thing….”

Stark is also a writer. Writing it seems would be too limiting, too two-dimensional, for Stark who’s trying to “write in space.” Meaning she wants to take these thoughts, these ideas that move her or stir her, and translate them into something multidimensional.

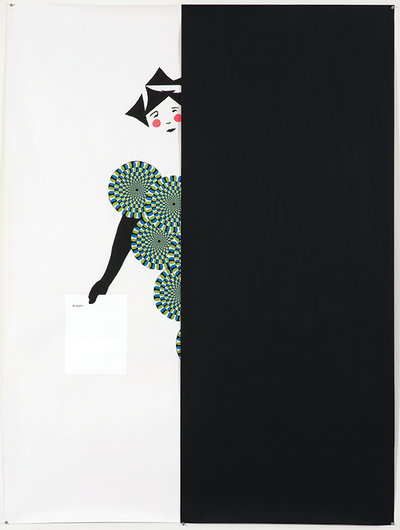

Frances Stark, Chorus Girl (a part), 2008, paper collage, graphite on paper, 76 × 58″. Private collection. Both images courtesy of greengrassi, London, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

She doesn’t think of her work as that personal. “I’m not painting a picture of myself…I mean who would care about me…it’s not interesting. I want to be a brain more than a name,” she says.

Emily Dickinson, David Foster Wallace and Henry Miller are just a few of Stark’s favorite poets and writers who figure prominently in her work. She falls in love with sentences and phrases and they form the basis of her compositions. The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock (1993) is an annotated version of T. S. Eliot’s poem. Chorus Girl (2008), Chorus Girl (a part) (2008) and the rest of the series come from the book Ferdydurke by Witold Gombrowicz. These collages appear in repetition as a conceptual reflection that “this is coming from a book, and you know there’s that copy and that copy and that copy, so it’s a kind of amplification of this phrase and a way to picture a phrase but I wanted to show this whole passage from this book.”

In To a Selected Theme (Fit to Print) (2007), Stark used a poster in her studio by Robert Mapplethorpe of a yawning David Hockney. She wanted to share it so it became part of a still life. “I never know what something is going to look like because I don’t have a technique,” she says.

Right before one of her exhibitions, she became fixated on the phrase “structures that fit my opening.” At the time, she says, “I had to fit all of these things that would fit into an opening and opening is a word you hear in art, ‘oh we’re going to have an opening’…so I just began to play with that phrase and I began to think about it more deeply…and it turned into a snail…” that became the work Structure That F(its my opening) (2006).

Frances Stark, still from My Best Thing, 2011, digital video, color, sound, 100:00 min. Hammer Museum, Los Angeles. Purchase. Image courtesy of Gavin Brown’s enterprise, New York, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

While Stark was on the tenure track at the University of Southern California she found herself saying yes to everything that came her way, from exhibits to articles. “Bobby Jesus”—a character name for a real person—came into her life at the time, and her film Bobby Jesus’s Alma Mater b/w Reading the Book of David and/or Paying Attention Is Free tells the story of their “mutual education.” As she says, “I taught at what people universally referred to as the University of Spoiled Children, and he went to school at the University of South Central, which we all know means the streets, and with my frustrations with the university environment I was trying to come to terms with how can art educate and what is the role of artists…and how can a middle-aged female white artist have any kind of relevance or significance to someone who grew up, and around, the criminal justice system…”

In 2012, Stark received tenure at USC’s Roski School of Art and Design. In December 2014, she resigned in protest with the administration over transparency and ethical issues. Later that spring, in a big news story, the seven students in the MFA program withdrew in protest as well.

By the end of UH-OH, if you study every work closely, you’ll see patterns emerge, ideas that repeat. “People fall in love with [Stark’s] brain,” says Ali Subotnick, curator at the Hammer. It’s understandable—her work is cerebral, inquisitive, riveting, puzzling and often just plain pleasing to behold. UH-OH certainly provokes, yet by the end of the show you might still wonder: “Who is Frances Stark?”

Sarah Baker is a contributing editor for Art New England.