The Arts Army

“Artists, the truth-seekers of society, will ascertain quite quickly who this enigmatic and vengeful Donald Trump really is.”

Mohamad Hafez, His Majesty’s Throne, plaster, paint, found objects, rigid foam, fabric, LED lights, antique picture frame, 48 x 48 x 30″.

CONNECTICUT

Lucy Gellman

It’s just past noon on December 27, 2016, when Lucy McClure’s first email pings into inboxes across Connecticut. She gets right to the point: The message is for nasty women with creative tendencies, who should continue reading if they’re worried about losing their civil liberties under Donald Trump. In a serif font the size of a small child’s finger, she lays out next steps.

“We are a group of people in CT who believe that solidarity, freedom, support and expression are of the utmost importance in our current and near-future political climate,” she writes. “As artists…we aim to stimulate conversation that may lead to further community involvement.”

A New Haven based photographer, McClure is one-third of the curatorial team behind the Nasty Women Connecticut art exhibition, opening March 9 at New Haven’s Institute Library (IL). Like co-curators Sarah Fritchey, gallery director at Artspace New Haven, and IL director Valerie Garlick, McClure had been optimistic last November 8. And then the results started rolling in.

“This,” she wrote to friends on the morning of November 9, “is not the American dream.”

Her response—organize first, mourn later—speaks to a burgeoning post-election sentiment in Connecticut. Across disciplines, artists are redoubling their commitment to craft, blending the boundaries between multimedia expression and social activism. Some, like McClure, are offering up exhibitions as a rallying cry. Others see these first months under Trump as a reminder that the system has been broken for a very long time, and this is just another reason to stay involved.

By November 8, 2016, Connecticut’s arts institutions were already smarting from a $1.73 million cut to funding for schools, libraries and museums. The election of someone in favor of opening libel laws on journalists and arts practitioners, said Andy Wolf, New Haven director of Arts, Culture and Tourism, felt like another massive blow.

“It could be a very dark chapter for the creative sector,” he said. “Artists, the truth-seekers of society, will ascertain quite quickly who this enigmatic and vengeful Donald Trump really is.”

“We cannot allow gripping insecurity, fear and lack of power to paralyze our community, our ideas and our hopes and dreams for America,” he added, invoking the words of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. “…I count on our Connecticut Delegation to stand tall and to confront the distortions and scapegoating that is about to come down on all of us.”

Some Connecticut artists—particularly those who have been blurring the lines between political activism and traditional art forms for some time—aren’t counting on anyone to stand tall but themselves. In New Haven, community organizer Hanifa Washington never expected her bimonthly spoken word series, Literary Happy Hour, to become a defiant political act. It was just that as Trump rose to power, the series—which celebrates writers and poets of color, women, gender nonconforming identities and varying ages—took on an added significance.

“Everything we do has political power and becomes a statement,” she said. “My politics are justice, fairness, love…These are very uneasy times, and I think, for me, having an event like this happen with frequency is important for me to not get sick…physically and emotionally.”

But Literary Happy Hour has also become, in the months since the election, a chance for her—and the statewide community of poets and writers who show up for the events—to assess the collective and individual traumas that they are feeling, and exercise agency around it.

“This is what literary work has always been, which is a peaceful protest,” she said. “Keeping it growing is a political act. We’re going to peaceably gather; we’re going to organize…you never know what’s coming out of those conversations and those connections.”

l. to r. Luis Antonio, Kiki Lucia and Kendra Fiercex in Escapade: An Unusual Experience, Lyric Hall Theater, October 2016. Photo: Anjel Perrone.

She’s not alone in that kind of cautious optimism. In a New Haven studio packed with dollhouse-sized models of blown-out buildings in Aleppo, suitcases wedged open to three-dimensional vignettes of Syrian life, and a miniature tool kit of broken lighting filaments, tiny exposed wires, and dust-covered screws, Syrian-American artist Mohamad Hafez bridges visual art, political commentary and activism with a simple directive. Look closely. And find it within yourself to understand these Syrian lives unlived, these hearts stopped prematurely.

“The power, I think, in modeling destruction captures something that other forms don’t,” he said. Before him sat a doll-sized dinner table, birthday cake uneaten at its center, covered in concrete dust and tiny mortar shellings. “We have been desensitized to the gruesome photos, and the dead, and the wounded. Our hearts and minds are not built in a way to witness so much atrocity. But I put that emotion into a high-detail model of destruction, then people engage with it and realize what it means to live in such a situation.”

An architect by day who dedicates much of his spare time to New Haven’s resettled refugee population, Hafez was working on these models, years before Trump’s ascension, as a way to connect him to the country he’d left when he was 15. But as he watched Trump speak out against women, Muslims, immigrants and refugees, they took on a different meaning and urgency.

“I am astonished at how somebody could get away with so many offensive things and still make it to the presidency,” he said, motioning to a large rendering titled His Majesty’s Throne, in which a man with hints of Donald Trump, Saddam Hussein, Hosni Mubarak and Muammar Gaddafi sits on a gilded toilet, defecating on hundreds of small houses below.

Translating those values more domestically—or trying to—is teacher and dancer Luis Antonio, who first presented his drag-dance mash-up Escapade: An Unusual Experience at the city’s Lyric Hall in late 2015. Now, he’s creating a new piece, Bad Hombre, to premiere sometime this year. His hope is that artists will take it as a cue: to create, unabashedly, as themselves—and urge progressive action in the process.

“As an out, Latino man, I definitely feel like it’s political,” he said in an interview. “If we need to fight for our rights, then we will. We’re going to breathe, take a second, hope for the best. And then we’re going to live day by day. Having signs that say ‘Fuck Trump’ is exciting. But I think that having art that is going to inspire in a different way is going to play a very important role.”

Janie Cohen, In Our Republic, November 2016, cotton, thread, leather, wood (with vintage handmade doll dress and leather baby shoes, barn door), 14 ½ x 11 ¾”. Photo: Chris Dissinger.

VERMONT

Amy Lilly

Janie Cohen’s recent singular work in fabric, In Our Republic, is disturbing—and not just because the antique doll’s dress she adorned with a yellow star evokes Nazi policies of dehumanization and worse. It alarms because it resonates with current times.

“This is definitely inspired by Steve Bannon and the guys,” says the longtime director of the University of Vermont’s Fleming Museum of Art, referring to President Donald Trump’s senior counselor and White House strategist. Cohen has been making hand-sewn cloth works for more than 25 years. At the time of the election, the presidential candidate’s calls for a mandatory registry of American Muslims sounded all too familiar. “All the hate they’ve been inspiring is mind-boggling,” she says.

Cohen is one of many Vermont artists who are engaging with Trump’s rhetoric and his administration’s policies as they unfold. The four described in this article are only a tiny sampling from a state with a firm tradition of experimentation in political art. Artists’ groups from Bread and Puppet Theater, active since the 1960s, to the Anthill Collective, a group of muralists who formed five years ago, have fostered a sense in Vermont that art matters beyond its own rarified arena.

Just last year, for example, artists working in Burlington’s scrappy South End district created a satiric sidewalk installation, called Miroville, that prompted Mayor Miro Weinberger to withdraw his recommendation for a zone change that would have gentrified the area.

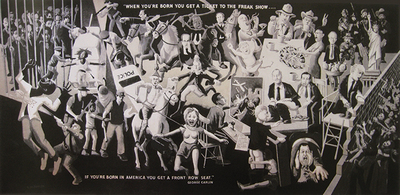

Al Salzman, The Freak Show, acrylic on canvas, 8 x 16′. © Al Salzman, 2016.

While it’s unlikely that artists will have such a direct effect on the national scene, that hasn’t stopped Al Salzman. At 83, the painter may be the state’s most senior and most explicit practitioner of political art. His recent 8-by-16-foot acrylic paintings, done in a figurative style reminiscent of social-realist murals such as Orozco’s The Epic of American Civilization (1932–34) at Dartmouth College’s Hood Museum of Art, skewer public figures that he sees as morally depraved and commemorate their victims.

The Freak Show (2016) unfurls in a violent display of the harm caused by American politics and its corrupt practitioners, and no one is spared. A white policeman shoots a black man in the back; a contract worker manipulates a drone from afar; Bernie Sanders, dressed as the Tin Man and mounted on a horse, aims a lance at Hillary Clinton, whose Goldman Sachs-embossed briefcase leaks money; various Bosch-like political figures swallow tiny humans; the Statue of Liberty scowls, middle finger raised. Framing this panoply is a crowd of black men behind bars and immigrants trying to reach over a brick wall that Trump is building, trowel in hand.

“I’m quite contentious,” Salzman admits. “I don’t abide by, what do you call them, moderates’ rules.” The artist grew up influenced by German Expressionism, the New Deal and protest art; he counts among his heroes Francisco de Goya and Leon Golub, for their series critiquing Spanish society in the 1790s and the Vietnam War in the 1970s, respectively.

The one downside of making protest art, he notes, is that galleries won’t sell it. “That stuff is being largely ignored [in the art world],” Salzman laments, but he adds that “now is the time” to include it.

Leslie Fry, an award-winning sculptor whose new work in bronze was recently shown on the grounds of the deCordova Sculpture Park and Museum in Lincoln, MA, fears that art’s potential impact pales in comparison to, say, that of late-night comedians. Sculpture requires that viewers seek it out to experience it in person, and such audiences are self-selecting. “It’s preaching to the choir,” she says.

Fry has created feminist art in the past. An early work in sheer fabric, for example, gathered in the shape of a bodice or teddy and called Lips Speaking Together embodies the gendering of language. Yet Trump’s rise impacted Fry’s newest work subconsciously. Having spent more than a year building up a series of abstract concrete sculptures from their bases, Fry found herself topping them off during election season with drooping phallic shapes.

The artist’s sense of humor and playful sensuality find new expression in these works. The bases are architectural pineapple-like shapes with splayed leaf-like elements curving up or forming a tripod. These support a slumping phallus stained translucent yellow in Pout, and a translucent-pink melting swirl in Twist. Fry used industrial Spandex to shape the wet concrete. That method is most evident in the layered buttock-like shapes of Swell, stained a darker pink and supporting a trunk form covered with tactile knobs.

Fry says she had previously planned on placing an egg shape peopled with tiny heads on one base. But somehow the reference to thinking minds gave way to the suggestively corporeal.

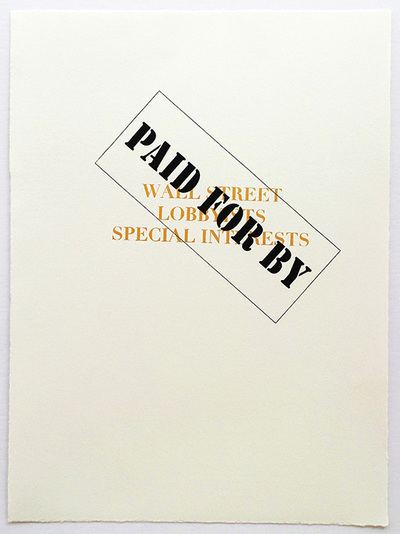

Julia DePinto, Paid For By, 2017, screenprint on paper, 15 x 11″.

At 29, Julia DePinto is too alarmed by Trump’s anti-humanistic stances to have much time for humor. DePinto, of Columbus, OH, was in residence at the Vermont Studio Center during the month surrounding the election. Cheered by weekly anti-Trump protests on the streets of tiny Johnson, VT, she began to respond to the president-elect’s Tweets in her text-based conceptual art.

“His messages are pretty clear and terrifying,” notes the artist, who trained in printmaking and is inspired by conceptual artists such as Jenny Holzer and Christopher Wool. DePinto chooses certain phrases that resonate personally and reworks them in screenprints. One, Unnatural Born Citizen, reads “(un) nat-ur-al born cit-i-zen” on otherwise blank paper. The stark work actively dismantles meaning while also illustrating its breakdown. Its use of dictionary conventions, meanwhile, calls to mind sources of fact, otherwise missing in Trump communications.

Another work, Paid For By, positions those words in bold caps inside a stamp-like rectangle that’s laid atop a list of who’s paying: Wall Street, lobbyists and special interests. DePinto took Trump’s campaign tweet, “Crooked Hillary is bought and paid for by Wall Street, lobbyists and special interests,” and created the graphic to represent the continuity of the accusation in Trump’s own cabinet choices.

DePinto worries, as do many artists, about Trump’s threat to the National Endowment for the Arts. But that seems like one of the least worrisome concerns of his presidency. As Fry puts it, the real question is, “Who can now affect change in the minds of the people who did support Trump?”

Jay Critchley, Miami Beige—island of abandoned luxury proposal, 2016, digital image.

MASSACHUSETTS

Christopher Busa

If we ask the question of what Russian artists did under the red glow of communism, we can answer that Kazimir Malevich, Wassily Kandinsky and Marc Chagall flourished. They found freedom in constrictions by filtering politics through a scrim that made the message metaphoric, parabolic and all while eluding censorship. Now under the orange glare of capitalism cast by the Trump administration, we can expect new forms of elusiveness. Two contemporary artists from Provincetown, MA, are examples: Lauren Ewing is a sculptor and installation artist and Jay Critchley is a conceptual artist, multi-media activist and writer.

Chameleon-like Critchley recently launched a public media protest against global warming at performance events in Miami, Los Angeles, via e-blasts and on his website. He used the Florida state seal to promote the project, Miami Beige—island of abandoned luxury. Recently, Rick Scott, the governor of Florida and a denier of climate change, ordered Critchley to cease and desist. Critchley, in his defense, offered a simple fact, inconveniently presented to the governor: Miami, near Trump’s presidential retreat, is listed as the number-one most vulnerable city on our planet, with billions of assets at risk from rising seas. Critchley’s lawyers cited First Amendment rights and he has continued with his protest.

Critchley’s career as a conceptual artist includes a long list of corporate personas. His shape-shifting spectacles are always accompanied by a costume appropriate to the particular theme, defusing angry protest into witty celebrations. Each involves an element of cleaning, purging, elimination, forgiveness and restoration of balance from a threat of disequilibrium. He challenges the coercion of corporate and government power with gentle chidings so obvious they become uniquely comical, mixing purpose and persona into an original Critchley signature. All of his art has been performative with the exception of his Old Glory Condom Corporation, where he used the American flag on his “corporate logo” which he emblazoned on prophylactic sheaths, connecting sex with patriotism.

America has never had a modern president, like Trump, who has been so frankly a businessman. Critchley is also a “business man” having created countless “companies” by printing his name as CEO on the linen letterhead of his fictitious corporations such as the Nuclear Recycling Consultants (NRC), TACKI (Tampon Applicator Creative Klubs International), or any other cause he thinks would address an urgent contemporary need. Trump’s wealth, though, may not be a cultivated wealth of philanthropic sharing, but a vulgar wealth of private hoarding. This is the opposite of artists like Critchley whose desire is to utilize his gifts to make a selfless contribution to society.

Laura Ewing, like Critchley, is also using her gifts in this way. She found her way into the heady world of conceptual art following her immersion in the land art and site-specific sculpture that emerged in the 1960s, influenced by the earthworks of Robert Smithson. She then became the first woman to head the sculpture department at the Rhode Island School of Design. Now, the town of Provincetown has awarded her a major commission to produce an AIDS memorial to be erected on the town hall property next year.

Ewing’s proposal is a horizontal monument of solid stone with the top surface sculpted in an exact replica of a single moment in the ocean, never to be seen again, that she captured in a photograph. Provincetown was one of the first responders to the AIDS crisis in the nation. This memorial will evoke the endurance and resilience of a community during any period of rough turbulence.

Ewing will use three blocks of dark grey marble, each three feet wide, nine feet long and two and one-half feet high, with the sides made to fit together snugly. The top surface will be milled from overhead by a multi-axis robot that will carve the delicate angles of ocean waves, including the fine “capillary waves,” like fingerprints, which the wind uses to get a better grip on fluid water. Now an instant on a sector of the ocean will be forever remembered in stone.

Visitors will be able to look at this surface and circumambulate the memorial, contemplating instances in the history of the Provincetown community during the AIDS crisis, with one side devoted to poetry curated by Provincetown poets Marie Howe and Michael Klein, editors of In the Company of My Solitude: American Writing from the AIDS Pandemic. Ewing, by fashioning a rectangular block of stone, creates a chunk of absence. This space evokes the living memories, feelings, spirit and solidarity of community. “I have great faith in the strength of the arts, music, poetry, film, dance and all the visual arts and I do not think they will be deterred in the least by the Trump administration,” she wrote in an email. “My worries are for the environment: water quality, breathable air in our cities, species preservation, global warming threatening all coastal communities around the world, not to mention all of Alaska.”

Critchley is thinking about creating an Intervention with Trump, a project he might create on paper this time. There would be a pumping oil derrick on the East Lawn, fracking with rumbling bedrock, and new buildings for corporate offices. There is a lot of empty, unused space around the White House. It could be a place to bring corporate leaders together or a national guesthouse for the president’s friends, Critchley suggests. If solar panels and a modest wind farm were set up, the District of Columbia could become free of utility costs. “My installation at the White House is not to re-green Washington, but to turn the site into a fossil-fuel producing site,” he says.

“Artists are extra-sensitive receivers and they will not be turned away from speaking their hearts, nor can the radical openness, which keeps art alive and relevant, be impaired. As artists,” Ewing wrote, “We face the future with oceanminds [sic] and wildhearts [sic].”

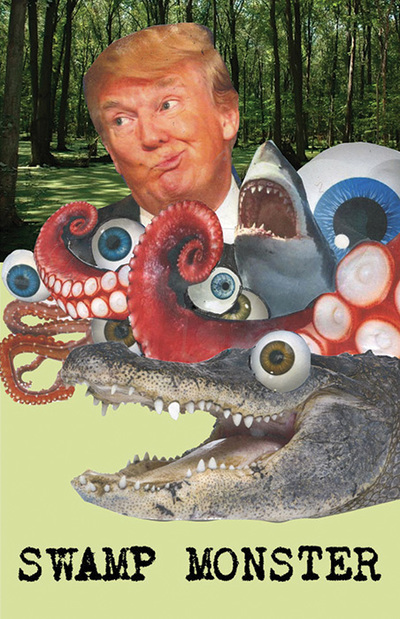

Charlie Hewitt, Swamp Monster, 2016, 8 ¾ x 13 ½”. From stealthisprint.com.

MAINE

Katy Kelleher

“Artists aren’t any more responsible than plumbers to communicate political feelings,” argues Charlie Hewitt. “But they do have the unique ability to illustrate their ideas.” Hewitt is a printmaker, documentary film producer and sculptor who, after spending years in New York, recently returned to his birth state of Maine. His timing couldn’t be better. As artists, he argues, “we’ve gone through 30 years of making luxury goods for Wall Street buyers, objects tailored for sale. We’ve had time to think and be playful in the arts.” Now, he says, things are about to change.

Hewitt is championing this change with his most recent project, Steal This Print, an interactive website and hub for collaboration that invites both amateur artists and professionals to submit their politically inspired art. Hewitt is a longtime Democrat, and says he “came alive in the 60s,” participating in civil rights protests and anti-Vietnam rallies.

“I’m so blue collar it’s almost sick,” he adds. “I’m not made for restaurants and expensive wines—I’m built for what will be happening.” While many Democratic-leaning artists may feel the urge to weep as Donald Trump threatens to erode our rights (and pollute our environment and corrupt our government), Hewitt reminds artists to work from a place of “humor and joy.” “We’re going to be a little dinged up at the end of this,” he says, “but we’re getting closer to each other. Our communities are tightening up.” Maine, he adds, is an excellent place to do that, thanks to the collaborative nature of the artistic community.

For ceramicist Ayumi Horie, the issue of connection is central to her work, both as an independent creator and as a co-founder of The Democratic Cup, an initiative that seeks to raise money for progressive causes through selling thoughtfully illustrated simple white mugs. Proceeds will be donated to organizations that fight for LGBTQIA rights, gun reform, gender equality, women’s health and combating systemic racism (customers are asked to vote for the cause most important to them, and funds will be distributed accordingly). “From the beginning, our focus was on inspiring deeper, more meaningful and civil conversations about being civically engaged,” she explains. “Our mission is to create a human connection and to inspire empathy. I think there was an incredible lack of empathy in the discourse around this election. And this kind of deep core philosophy change has to happen at a micro-level.” The mugs bring political issues to the table—literally.

One of The Democratic Cup’s best sellers features a drawing by illustrator Scott Nash of a small bird speaking into a microphone. While it functions as a tribute to presidential candidate Bernie Sanders, it also speaks to, as Horie describes it, “the power of one small voice. It’s about how we can amplify each of our voices to think about our mutual responsibility to our fellow citizens.”

Although Horie recognizes that many artists are frightened by the incoming administration and what it may mean for our country, she holds out hope that “slow activism” can help return a sense of responsibility and kindness to American politics. “A lot of the conversations we’re hoping to encourage aren’t about changing someone else’s mind, but about seeing where they’re coming from,” she says. “Having [cups] catalyze the conversation feels like the right medium.”

Other artists are seeking to strengthen local community ties as a way to counteract divisive politics. This was readily apparent at “The Other Inaugural Ball” which took place on January 21st at the Mechanics Hall in Portland, ME. Organized by artists and educators Louise Kennelly and Jocelyn Lee, the event featured performances by the Theater Ensemble of Color, live music, an open-mic emceed by award-winning author Bill Roorbach, and Fatuma Hussein, founder of the Immigrant Resource Center of Maine, as the keynote speaker. “Articulating your humanity in a public setting is called for right now,” says Kennelly. Art, she argues, is an important force for change because of how it articulates a diverse range of human experiences. It’s a tool to communicate, one that forges bonds of empathy and understanding.

“Artists have been doing this work for a long time, but they have been marginalized,” she says. “Arts need to be more central to our society. We empower the economic engine. We know how to collaborate and be innovative. The artistic community has been doing that for years, without getting a lot of credit.” “Unfortunately,” she adds, “we’re not at the table where decisions are being made.”

Kate Beever, a Portland-based musician, music therapist and member of the Maine Arts Commission, agrees that politicians do not adequately represent the needs of artists, nor are their voices always heard on a local level. Many of the incoming president’s policies threaten the very lifestyle of Maine artists. “Living as an artist,” she explains, “you have to worry about access to healthcare and about paying your bills. Most artists that I know are self-employed, and not necessarily by choice—it’s because they’re contractors.” Like much of the self-employed population, many artists rely on the ACA for medical care, which the new administration and the Republican-controlled Senate and Congress want to repeal.

“When Republicans are cutting funding for healthcare and education, that hurts our artistic population,” says Beever. “Overall, it isn’t good for artists when really conservative people are running things.” However, she says this has “already been happening.” “The arts have lost funding under the Democrats, too. But I do think the artistic community is resilient. We’ve been forced to struggle.”

And now the struggle may be opening up, becoming even more visible as the so-called creative class expands. This could be a good thing for the anti-Trump resistance. “While many people still think of the arts as an extracurricular thing or for enrichment, the creative economy is becoming more central to the overall economy,” Kennelly says. Plus, the question of who qualifies as an artist is ever-expanding, letting more and more people, from bakers to banjo players, join the ranks of the creative class.

“It’s become important to work more loudly, more purposefully and get organized more quickly to fight against bigotry and hatred.” But the arts, Kennelly says, can play a central role in this battle. “Obviously, we’re not there yet. But the arts army is getting bigger.” And they’re going to fight.

Lucy Gellman is a reporter for the New Haven Independent and station manager of WNHH-LP where she hosts a weekly podcast about food. Amy Lilly writes on the arts and humanities for Seven Days, Vermont’s alternative newspaper. Christopher Busa is the founder and editorial director of Provincetown Arts, provincetownarts.org. Katy Kelleher is a writer, editor and teacher who lives in Buxton, ME. Her first book, Handcrafted Maine, is due out in July from Princeton Architectural Press.