Ranalli’s Whims of Nature

Daniel Ranalli often takes his studio to a Cape Cod beach. It is there where he works with nature, with its ebb and flow and constant changes, with the control an artist seeks and with the act of letting go.

Traces, a twenty-year survey of Ranalli’s work, created and photographed on the sands of Cape Cod, is on exhibit at the Provincetown Art Association and Museum, now through January 16, 2011.

A professor at Boston University and director of the graduate program in arts administration, Ranalli first became enamored with the Cape thirty years ago. From his home in Wellfleet, he goes out to explore the beaches, “developing an almost autobiographical relationship to the ecology and the environment,” he says one late summer afternoon, sitting on the deck of his home not far from the Wellfleet Town Pier. Ranalli is relaxed, yet there is intensity in his gaze that expresses a visceral commitment to exploring nature’s wonders in his art.

Nature is often an inspiration for artists, but Ranalli’s photographs are not the typical images you see of land and sea. “I was interested in developing my own relationship to this place that was very particular, very personal…a sort of personal natural history…I didn’t want to paint another sunset or another sailboat in the harbor.”

His canvas is a tidal beach or the dunes, and his paint, the raw materials he finds there—sand, shells, stones, seaweed, and sea creatures.

His canvas is a tidal beach or the dunes, and his paint, the raw materials he finds there—sand, shells, stones, seaweed, and sea creatures.

The works he built on the Cape Cod Bay beaches were the result of just walking and looking and thinking, he says, “to breathe in the experience.” His series of photographs record the ephemeral whims of nature. Tides, winds, and the desires of sea life have an impact; his constructions are gone not long after he shoots the photograph. What remains are the images of Ranalli’s creation and the results of nature’s tinkering.

“I think of the photography in many cases as documentation,” Ranalli says. “A lot of the pieces are sculptural objects built out of seaweed or clamshells or horseshoe crabs; they’re installations. And they’re not going to last. The only way to have anyone see them is to photograph them.”

A common thread in his work is “the notion of found marks and chance,” he says, thinking of a series he did of chalkboards he photo-graphed at Boston University. He combined these diverse images digitally into photomontages of fragments of words and mathematical symbols, which come together in cryptic associations.

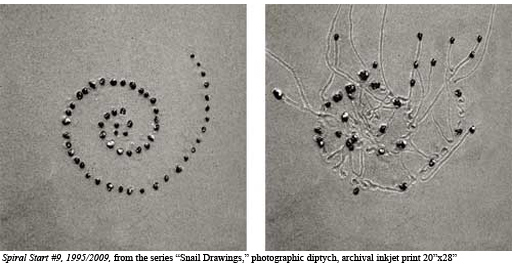

Referring to his series Snail Drawings in the Provincetown exhibition, Ranalli describes how he set the process in motion by arranging a collection of snails in a specific shape—circle, spiral, or triangle—and then taking a photograph to mark the starting point. He watched as the snails moved out, and within fifteen minutes (apparently a snail’s pace is not so slow) they created their own random composition which became the subject of another photograph. Snail Drawing: Spiral Start #9 begins with a spiral—actually a self-portrait of a snail, he says with amusement—and then the snails take off. In Snail Drawing: Pythagorean Theorem, Ranalli boxed in four snails with eel grass and then photographed their escape.

“I basically choreographed them but then they danced their own dance. No matter how I set them up there’s always surprise in what they do,” Ranalli says. “The notion of chance plays a big part in all of my work,” which is almost always photographic. “I feel that life is composed of two parts planning and one part chance…I think the snail drawings are a metaphor for that.”

“I basically choreographed them but then they danced their own dance. No matter how I set them up there’s always surprise in what they do,” Ranalli says. “The notion of chance plays a big part in all of my work,” which is almost always photographic. “I feel that life is composed of two parts planning and one part chance…I think the snail drawings are a metaphor for that.”

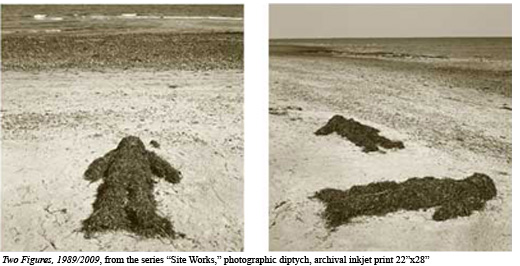

In Every Mark I Make, Ranalli arranged a double line of clam shells at water’s edge and then photographed them as the incoming tide covered them. In what he calls Environmental Interventions, he used seaweed to build a five-foot pyramid and also created larger-than-life human figures with this same material. The stones on the bay beaches, which are an encumbrance to bathers, became Ranalli’s building blocks. He arranged them in a circle around a rock, like some sort of primitive ritual site. Again using stones, he worked in the negative, removing some to form a neat rectangle of sand. He discovered that a collection of horseshoe crabs could form a tidy triangle.

Ranalli became interested in whale strandings after witnessing the beaching of twenty-four pilot whales in Wellfleet in 1993. He delved into the history of whales and his Whale Strandings series is the result. The images he created with woodblock prints of whales are based on the ones in shipboard journals and logs, which he discovered in his research.

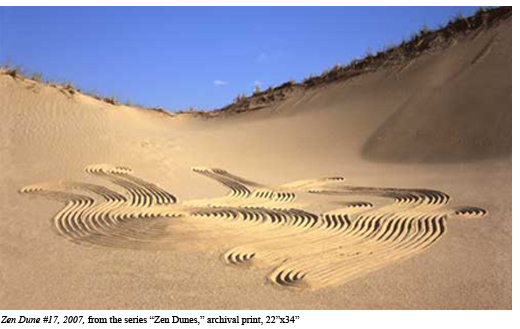

Perhaps the most beautiful photographs in the exhibit were shot on the Provincetown dunes, where he has spent a number of sojourns in primitive dune shacks with his wife, Tabitha Vevers, also an artist. Inspired by what he saw on his trips to Asia and the meditative practice of monks raking stones in Zen gardens, Ranalli raked the sands in elegant, curvaceous sweeps of various shapes. The color photographs he took with his four-by-five view camera capture the winding curves he spontaneously drew with a wooden rake, which, he says, evolve out of “a notion of wanting a kind of spiritual relationship to the landscape.” And, he adds, “The best of them (those meandering curves) almost look like they drew themselves.” Perusing the photographs, you can imagine Ranalli alone in the vast space of the dunes he loves, quietly drawing with his rake. And within two days, the work is gone with the wind.

Perhaps the most beautiful photographs in the exhibit were shot on the Provincetown dunes, where he has spent a number of sojourns in primitive dune shacks with his wife, Tabitha Vevers, also an artist. Inspired by what he saw on his trips to Asia and the meditative practice of monks raking stones in Zen gardens, Ranalli raked the sands in elegant, curvaceous sweeps of various shapes. The color photographs he took with his four-by-five view camera capture the winding curves he spontaneously drew with a wooden rake, which, he says, evolve out of “a notion of wanting a kind of spiritual relationship to the landscape.” And, he adds, “The best of them (those meandering curves) almost look like they drew themselves.” Perusing the photographs, you can imagine Ranalli alone in the vast space of the dunes he loves, quietly drawing with his rake. And within two days, the work is gone with the wind.

Closely tied to nature’s wonders, both its regular rhythms and its constant change, Ranalli’s work sensitizes the viewer to the daily spectacles of sea meeting land. His work straddles the boundary between abstraction and realism. The forms he constructs are geometric and abstract, yet they are set with real materials on nature’s stage.

As Ranalli says: “What I’m really interested in is changing the way people see the environment. I want them to look at it more closely.”

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Deborah Forman is an editor and journalist who has been covering the arts for thirty years. Her book on the Provincetown artist colony will be published by Schiffer Publishing in the spring of 2011.