Sound Sculptures

Whether designing interactive sound environments or performing on individually built and designed instruments, six New England artists combine sculpture and sound to create intriguing sonic landscapes.

Whether designing interactive sound environments or performing on individually built and designed instruments, six New England artists combine sculpture and sound to create intriguing sonic landscapes.

Artist and inventor Paul Matisse, grandson of Henri, lives and works in a former Baptist church in Groton, Massachusetts. He fabricates his sculpture in the ground-floor studio and machine shop. The soaring sanctuary upstairs houses the Kalliroscope Gallery, named for his crystal and liquid-filled devices that create fluid patterns of reflected light. He has always loved to make things. “I spent a good deal of time in bed with asthma between the ages of six and eleven, and my bed was filled with balsa wood chips and loose wood,” he says.

Since the early 1980s, Matisse has worked primarily with sound. His resonant aluminum bells produce extraordinary lingering tones that elucidate the space in which they reside. Among these are Athens Olympic Bell (2004), and Pythagoras (1987), part of Kendall Band, a trio of instruments at the Kendall T-station in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Designed to be operated by passengers, Kendall Band had fallen silent after more than twenty years, during which time the artist made nighttime repairs. This spring, the MIT Kendall Band Preservation Society, a student group guided by an instructor, has assumed curatorial responsibility and undertaken refurbishment. Pythagoras was reinstalled in working order on April 30,, 2011.

In May, the artist and his assistants were finishing a bell for a small wooded valley at a sculpture park at Chateau La Coste, in Aix-en-Provence in southern France. The upscale winery features the work of architects Tadao Ando, Jean Nouvel, Renzo Piano, and Frank Gehry, and artists Louise Bourgeois, James Turrell, and Richard Serra. The sleek cylindrical bell, which will be suspended horizontally between aluminum columns and rung with rubber and aluminum hammers, is slated for installation this summer.

A funkier aesthetic informs the work of Cambridge-based Jason Sanford, whose band, Neptune, combines spoken word with amplified sound. They have been playing experimental music on homemade instruments since 1994 and have a new release due out in the fall on Northern Spy records. “We’re loud,” Sanford says, “We’re an earplug band.” Although he has a BFA in sculpture from UMass Amherst and an MFA in studio for interrelated media at MassArt, Sanford considers himself a musician who makes instruments, which he wires and welds in a cramped basement and small backyard.

Among his early instruments are the Tupper Phone—two rubber bands stretched over a plastic container—and a thumb piano made from metal bristles shed by street sweepers. Later creations include a five-foot-diameter xylophone made from circular saw blades and a jagged thirty-five-pound scrap-metal guitar. Sanford also uses electronically generated sound. He is currently tinkering with white-noise machines he buys in thrift stores whose static effects range from warbler-esque to mind-numbing. Until now, he has not worked with computers.

“I draw a distinction between analog and digital,” he says. “The production of sounds is a performative process.” Sanford is chief vocalist for Neptune and his lyrics often originate in randomly derived “cut-up poems” from newspapers or magazines. “I’m interested in the boundary of musicality,” he says. “I’m looking for this threshold between talking and singing.”

In Bedford, Massachusetts, musician and sound artist Halsey Burgund also synthesizes speech and music, but uses computers and GPS technology along with traditional instrumentation. After studying geophysics and music at Yale, he crafted furniture, worked in high tech, and played in bands. His evolving, interactive sound pieces at the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum (2008) and the DeCordova Sculpture Park and Museum (2010) incorporate the voices of museum visitors in real time. Burgund received a 2011 Smithsonian Artist Research Fellowship grant to study the artistic uses of oral history and spoken word.

Burgund’s latest installation, Voices Without Faces, Voices Without Races: An Audio Journey, was at Boston’s Museum of Science this spring. The sound and video collage explored the experience of race through interviews with Massachusetts

residents who are heard but not seen. Asynchronous video streams shot from the windows of a car driving on Route 28 were projected on three walls to visually disorienting effect. “I didn’t want people to prejudge the voices based on the face of the person speaking,” Burgund says. Doing the interviews that form the basis of the piece “was like uncorking a bottle.…I’ve learned a lot. Race is one of those things you don’t talk about.” The artist designed computer algorithms to sequence random excerpts from the interviews and his composed music so that the conjunction of sound and image is never repeated.

Boston artist Catherine D’Ignazio teaches at RISD’s Digital Media Graduate Program. Her political work involving sound, public space, and performance explores what she calls “the new geography of fear and insecurity we face post 9/11. I am trying to measure fear in public spaces…to create an experience for the body to encounter.” In her 2009 piece, It takes 154,000 breaths to evacuate Boston, the artist ran the entire emergency evacuation route system in Boston and measured its distance in breaths, which she recorded as she ran. In the same year, she sang the blog posts of Iraqi citizens to her first son in an online project Iraq Lullaby Service.

Boston artist Catherine D’Ignazio teaches at RISD’s Digital Media Graduate Program. Her political work involving sound, public space, and performance explores what she calls “the new geography of fear and insecurity we face post 9/11. I am trying to measure fear in public spaces…to create an experience for the body to encounter.” In her 2009 piece, It takes 154,000 breaths to evacuate Boston, the artist ran the entire emergency evacuation route system in Boston and measured its distance in breaths, which she recorded as she ran. In the same year, she sang the blog posts of Iraqi citizens to her first son in an online project Iraq Lullaby Service.

Her project The Border Crossed Us, on the UMass Amherst campus in April, recreated a section of the Arizona/Mexico border fence erected in 2007 by Homeland Security. A 400-foot panoramic photo of the cement-and-steel-pylon fence obstructed access through a campus corridor. The real fence, and the enforcement accompanying it, has splintered the Native American Tohono O’odham Nation, whose lands straddle the US/Mexico border. D’Ignazio collaborated with Ofelia Rivas, a Tohono O’odham artist and activist, who recorded construction noise outside her Arizona home. These sounds, spliced with a blessing and eagle song Rivas sang to strengthen her people, created a soundtrack that was the emotional heart of the piece. “An international border divides our lands,” Rivas says. “The construction sounded like Mother Earth screaming. I don’t know if we will ever be able to a take the metal out of her.”

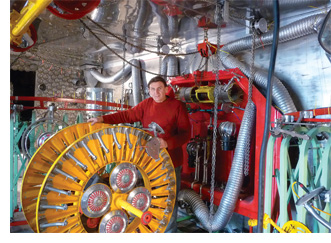

Hungarian-born sculptor and musician Viktor Lois recycles old machinery into sculptures that double as musical instruments. His wife, Taiwanese sculptor Yin Peet, with whom he sometimes collaborates, works mostly in granite. They have built their home and studios on the site of an old quarry in Acton, Massachusetts. Lois, who represented Hungary at the 45th Venice Biennale in 1993, is a self-taught artist. After mechanical training in high school, he took a job repairing typewriters. He created his early, table-sized instruments by an ingenious use of recycled typewriter carriages, bicycle parts, and guitar pick-ups. As Tundravoice, Lois has performed and recorded with musicians from Asia and Europe, playing on his Motor Guitars, Mechanical Drum, and bowed stringed instruments. Unmoored by Western musical structures, he produces tonalities more closely resembling Asian sonorities.

Lois cites the influence of the Russian constructivists and Vladimir Tatlin (and the scale of Tatlin’s envisioned Monument to the Third International) in creating his own massive instruments. The couple’s most ambitious multidisciplinary project, Container Man, is a bright red shipping container chockfull of musical machines, roughly configured as a “brain, limbs, head, and two hearts.” With twenty-two channels and a soundboard, it serves as both studio and stage, and they have toured with it in Taiwan and Eastern Europe.

Lois cites the influence of the Russian constructivists and Vladimir Tatlin (and the scale of Tatlin’s envisioned Monument to the Third International) in creating his own massive instruments. The couple’s most ambitious multidisciplinary project, Container Man, is a bright red shipping container chockfull of musical machines, roughly configured as a “brain, limbs, head, and two hearts.” With twenty-two channels and a soundboard, it serves as both studio and stage, and they have toured with it in Taiwan and Eastern Europe.

Composer and media artist Erik Carlson, based in Providence, creates site-specific compositions. His work has been supported by the LEF Foundation and the Rhode Island Foundation’s MacColl Johnson Fellowship in music composition. This year, he received a fellowship in new genres from the Rhode Island State Council on the Arts. He records and performs his layered meditative music, composed of repeated loops of guitar, keyboard, and collected sound, under the name AREA C.

“I have been a musician most of my professional career and have also worked in architectural preservation for the last eighteen years,” Carlson explains. “I combine my work as a musician with design work in the public and installation realm.” He devised the sound for Low Rez/Hi Fi (2007), a permanent, interactive collaboration with architect Meejin Yoon. Located in Washington, DC, the piece consists of twenty touch-sensitive poles that emit sound and LED light. Pedestrians trigger sound samples that blend with ambient city noise to create what the artist describes as a sidewalk “soundgrove.”

In early fall, Carlson will create an installation and a performance in the historic Ladd Observatory at Brown University, which opened in 1891. It houses a collection of vintage instruments including refracting and transit telescopes, and astronomical clocks. “We will be activating the whole building with sound,” he says. “I am interested in some of the antique equipment in the building…and will be investigating the architectural features as potential sound sources.”

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________

Anne Krinsky is a Boston-based artist whose work is in the collections of the British Museum and the Boston Public Library. Her recent solo shows include Anne Krinsky: A Provisional Space, at Soprafina Gallery, and Anne Krinsky: Time/Line, 2000–2010, at the Trustman Gallery at Simmons College, both in Boston.