PEM On the Rise

The Getty Museum in California. The Museum of Modern Art in New York. The National Gallery in Washington, DC. The Peabody Essex Museum (PEM) in Salem, Massachusetts. What’s weird about this list? The inclusion of PEM in the top tier of US art museums in terms of endowment, figures based on statistics compiled by both PEM and the Association of Art Museum Directors. PEM Executive Director and CEO—and AAMD President—Dan L. Monroe says that the museum already has raised $550 million of the $650 million campaign goal that will put it in this exalted group, with an endowment of $630 million by 2016. The only other New England institutions to make the cut are the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, where the endowment is $548 million, and the Harvard Art Museums, whose endowment is $507 million.

The Getty Museum in California. The Museum of Modern Art in New York. The National Gallery in Washington, DC. The Peabody Essex Museum (PEM) in Salem, Massachusetts. What’s weird about this list? The inclusion of PEM in the top tier of US art museums in terms of endowment, figures based on statistics compiled by both PEM and the Association of Art Museum Directors. PEM Executive Director and CEO—and AAMD President—Dan L. Monroe says that the museum already has raised $550 million of the $650 million campaign goal that will put it in this exalted group, with an endowment of $630 million by 2016. The only other New England institutions to make the cut are the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, where the endowment is $548 million, and the Harvard Art Museums, whose endowment is $507 million.

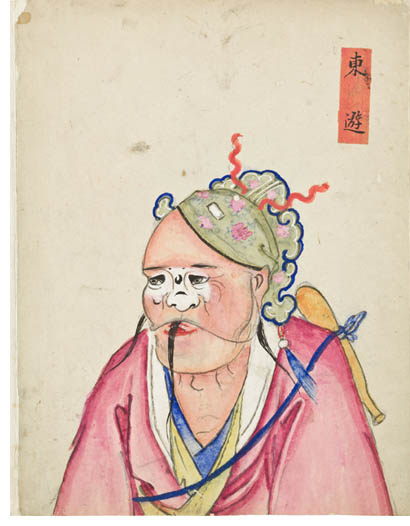

Harvard benefactors come from all over the world. Anyone with a Harvard degree is a natural fundraising target. The MFA, under director Malcolm Rogers, has also gone global, aggressively reaching outside New England for the first time, attracting wealthy collectors including Leonard A. Lauder, chairman emeritus of Estée Lauder, who has no Boston connections. Rogers accepted Lauder’s collection of 20,000 early twentieth-century Japanese postcards, which was a controversial move in some quarters. Japanese postcards aren’t exactly Rembrandts, after all. Did the MFA really need them? Rogers is very keen on material culture, though, and Lauder donated a seven-figure sum to care for his postcards and endow a curatorship of visual culture.

Where do PEM’s donors hail from? There is plenty of money on the North Shore, and huge speculation about the level of funding from Edward “Ned” Johnson III, the octogenarian head of Fidelity Investments, who is silent on the subject of his donations to local art museums—his contribution to the MFA’s American wing is said by a reliable source to be $100 million—but PEM is tight-lipped on the subject. The donors are not, however, all local. Like the MFA, PEM has assiduously cultivated donors from further afield. They come from Texas, California, even as far away as India. Two South Asian families have contributed substantially. And in 2008, the Bollywood actress Tina Munim Ambani became PEM’s first international trustee. PEM began collecting Indian art in 1799—long before the MFA was even founded—and with the acquisition of the Chester and Davida Herwitz collection of contemporary Indian art in 2000, it became one of the foremost repositories of art from the subcontinent.

Where do PEM’s donors hail from? There is plenty of money on the North Shore, and huge speculation about the level of funding from Edward “Ned” Johnson III, the octogenarian head of Fidelity Investments, who is silent on the subject of his donations to local art museums—his contribution to the MFA’s American wing is said by a reliable source to be $100 million—but PEM is tight-lipped on the subject. The donors are not, however, all local. Like the MFA, PEM has assiduously cultivated donors from further afield. They come from Texas, California, even as far away as India. Two South Asian families have contributed substantially. And in 2008, the Bollywood actress Tina Munim Ambani became PEM’s first international trustee. PEM began collecting Indian art in 1799—long before the MFA was even founded—and with the acquisition of the Chester and Davida Herwitz collection of contemporary Indian art in 2000, it became one of the foremost repositories of art from the subcontinent.

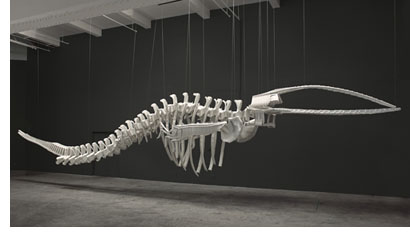

“We were the first Americans to do business with the Indians,” says PEM marketing head Jay Finney. “The Indians have less warm feelings about trade with the British than they do with us. We weren’t colonizing them. We were trading with them. It dates back to the founding of our country. Now we have the largest collection of contemporary Indian art in the world.” In the Herwitz Gallery there is a permanent display of Indian art. And in the atrium lobby is a huge mirrored sculpture by the greatest of contemporary Indian artists, Anish Kapoor. Due to Salem’s history as a city of seafaring merchants, PEM also boasts important collections of Asian export, maritime, and Oceanic art. What you won’t find there is a big array of Impressionist and other European styles that is the bread and butter of so many major museums.

“We were the first Americans to do business with the Indians,” says PEM marketing head Jay Finney. “The Indians have less warm feelings about trade with the British than they do with us. We weren’t colonizing them. We were trading with them. It dates back to the founding of our country. Now we have the largest collection of contemporary Indian art in the world.” In the Herwitz Gallery there is a permanent display of Indian art. And in the atrium lobby is a huge mirrored sculpture by the greatest of contemporary Indian artists, Anish Kapoor. Due to Salem’s history as a city of seafaring merchants, PEM also boasts important collections of Asian export, maritime, and Oceanic art. What you won’t find there is a big array of Impressionist and other European styles that is the bread and butter of so many major museums.

PEM has gotten the word out about itself by organizing shows that have traveled to New York, San Francisco, and other cities. The museum organized Fiery Pool: The Maya and the Mythic Sea, and The Emperor’s Private Paradise: Treasures from the Forbidden City, both of which drew record crowds to their host museums, and both of which featured non-European art. Another traveling show, Golden: Dutch and Flemish Masterworks from the Rose-Marie and Eijk van Otterloo Collection, celebrated the world-class holdings of that Marblehead couple.

Like most museums, PEM is chronically short on space, and $200 million of the campaign money will go toward an expansion designed by London-based Rick Mather Architects. The firm also did the expansion/renovations of Oxford University’s Ashmolean Museum and the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, among other arts institutions. The 175,000-square-foot expansion will be squeezed onto the museum’s current footprint; some older buildings will be torn down. Of the new space, which is due to open in 2016, 75,000 square feet will be for galleries, which means, among other things, that PEM’s gem of an African collection will once again be on view. Mather’s expansion “is not going to be an architectural statement,” says Finney. “It’s not a Frank Gehry kind of thing.” Of the five architects who participated in the museum’s charette, “Mather was the only one to design from the inside out,” Finney says. “He had a very thoughtful response to our space needs. It’s not ostentatious. There’s no wasted space. We’re down deep into developing ideas about art freight, etc.” The new space that’s not for galleries will be for back-of-house functions, including storage and conservation. Both the new galleries and the older ones will be brought to state-of-the-art in climate control, making it easier for the museum to get loans from other institutions. And there will be a new restaurant, with direct access from the street.

designed by London-based Rick Mather Architects. The firm also did the expansion/renovations of Oxford University’s Ashmolean Museum and the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, among other arts institutions. The 175,000-square-foot expansion will be squeezed onto the museum’s current footprint; some older buildings will be torn down. Of the new space, which is due to open in 2016, 75,000 square feet will be for galleries, which means, among other things, that PEM’s gem of an African collection will once again be on view. Mather’s expansion “is not going to be an architectural statement,” says Finney. “It’s not a Frank Gehry kind of thing.” Of the five architects who participated in the museum’s charette, “Mather was the only one to design from the inside out,” Finney says. “He had a very thoughtful response to our space needs. It’s not ostentatious. There’s no wasted space. We’re down deep into developing ideas about art freight, etc.” The new space that’s not for galleries will be for back-of-house functions, including storage and conservation. Both the new galleries and the older ones will be brought to state-of-the-art in climate control, making it easier for the museum to get loans from other institutions. And there will be a new restaurant, with direct access from the street.

Monroe says that one goal of the new space will be “taking the contemporary art program to another level from where it is now. There will be new initiatives in American painting very soon.” Currently, the contemporary art tends to be interventionist, with contemporary artists interacting with the historical collection. Monroe points out that “The work we’ve collected since our founding has been the art of its time. We don’t want to be known as a historical museum.”

This is the museum’s second major twenty-first-century expansion: One by Moshe Safdie, who has offices in Jerusalem, Singapore, Toronto, and Somerville, Massa-chusetts, opened in 2003, and among other things, created a vast new atrium lobby that stretches all the way to the roof. Unlike the Mather plan, the Safdie design was meant to evoke a “Wow!” response from visitors. The lobby is an exceedingly dramatic gathering place that gives visitors a sense of what is where in the building. You look up and around to find your way through the complex.

PEM already has a campus of twenty-four buildings in Central Salem—it’s more like a college than a conventional single-building museum. Many of those buildings are historic, from the late seventeenth-century John Ward House to the early eighteenth-century Crowninshield-Bentley H ouse to the stately brick 1804 Gardner-Pingree House, a Federal-style building by the celebrated Salem architect Samuel McIntire. The most striking is the Yin Yu Tang House, a sixteen bedroom home built late in the Qing dynasty (1644–1911). It took seven years to move the house from a rural village in China’s Anhui Province and reassemble it at PEM. The museum also owns the Phillips Library, a superb research facility in an elegant building, housing documents relating to the collections, to genealogy, maritime art, and even the Salem witchcraft trials of 1692. The Phillips, one of America’s great museum libraries, comparable to the library of the British Museum, is currently closed for a two-and-a-half year, $20 million restoration that, among other things, will make its 400,000 volumes more accessible to the public. Meanwhile, there’s a delightful show of some of its treasures in the main building, Unbound: Highlights from the Phillips Library at PEM. Among the objects in it is a page from the Gutenberg Bible, the first book ever printed in the West from movable type, dating from the mid-fifteenth century.

ouse to the stately brick 1804 Gardner-Pingree House, a Federal-style building by the celebrated Salem architect Samuel McIntire. The most striking is the Yin Yu Tang House, a sixteen bedroom home built late in the Qing dynasty (1644–1911). It took seven years to move the house from a rural village in China’s Anhui Province and reassemble it at PEM. The museum also owns the Phillips Library, a superb research facility in an elegant building, housing documents relating to the collections, to genealogy, maritime art, and even the Salem witchcraft trials of 1692. The Phillips, one of America’s great museum libraries, comparable to the library of the British Museum, is currently closed for a two-and-a-half year, $20 million restoration that, among other things, will make its 400,000 volumes more accessible to the public. Meanwhile, there’s a delightful show of some of its treasures in the main building, Unbound: Highlights from the Phillips Library at PEM. Among the objects in it is a page from the Gutenberg Bible, the first book ever printed in the West from movable type, dating from the mid-fifteenth century.

Another current exhibition of note is Shapeshifting: Transformations in Native American Art, which combines contemporary Native American art with historical examples, which, curator Karen Kramer Russell observes, were contemporary in their day. One purpose of showing the two together is to enable viewers to see the earlier works as examples of fine art of their time, not merely historical artifacts. PEM has collected Native American art since the 1800s; it was a pioneer in doing so.

Monroe, who is extremely proud of PEM, refuses to see it as out of the way. “For over half the population of Greater Boston, it’s easier to come here than to go to the MFA,” he says. And, he adds, there’s more parking.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________

Christine Temin was the art and dance critic at the Boston Globe for more than two decades and now writes for a variety of international publications. She has taught at Middlebury College, Wellesley College, and Harvard University. Her most recent book is Behind the Scenes at the Boston Ballet, published by the University Press of Florida.